There’s lots of GMing advice on the Internet. Apart from mine, that is. Some of it’s actually okay. Some of it sucks. But most of it’s just bland, dull, feel-good advice that doesn’t actually tell anyone anything useful. It’s basically just gamer aphorisms. Though maybe I should call them a%&-phorisms.

BURN!

What drives me crazy, though, is not all the useless, non-actionable a$&-phorisms like “be interesting” and “make sure everyone is having fun” and “always say yes” and “make failure more interesting than success” and all the other s$&% like that. What kills me is how repetitive it all is. Some GM will give a big flourish and offer some worthless received truth like he thinks he’s f&$%ing Socrates and then, suddenly, everyone is saying the same thing in their videos and blog posts and TikToks and Pinstagrams.

But what really, REALLY drives me crazy is when they all start parroting something that’s actually good advice. Well, it’s a piece of something that, with some effort, could be turned into good advice. Because, eventually, someone will ask me for advice about something and I’ll end up having to repeat that same bit of advice. Just another trained parrot squawking into the gaming void.

For example, I’ve been asked a few times how to start a homebrew campaign. And, more importantly, where to start the daunting worldbuilding process. And I have to give the same answer that all of my so-called peers do.

Start small and build.

But, unlike all of those other mindless automatons repeating the latest Colville claptrap, I’m not going to stop there and take a bow. I’m going to write another 5,000 words about exactly how to start small and build.

… With Blackjack! And Hookers! In Fact, Forget Homebrewing

There comes a point in every GM’s gaming career – in my case, it came right at the beginning of my gaming career – there comes a point in every GM’s career when they’re just f&$%ing done with the published, packaged crap that the RPG publishers keep barfing out. “That’s it,” they say, “I’m going to run my own campaign and write my own adventures and build my own world.”

And, thirty days later, they’ve given up on the hobby forever. Because worldbuilding.

Starting a homebrew game – that’s what it’s called when you design and run your own, bespoke games – starting a homebrew game is a really daunting prospect. Before you get to run your first adventure, before you get to design that first adventure, and before your players even get to make characters, you have to build an entire f$&%ing world. Or so you wrongly think.

Or so some of you wishfully think.

Depending on how you look at it, worldbuilding – inventing all the details about the world in which your game takes place – is either a terrifyingly huge and impossible task or it’s the only reason to ever even run a game. If you’re of the former mindset, worldbuilding is probably the thing that’s keeping you from running your first homebrew game. And if you’re of the latter mindset, worldbuilding is probably the thing that’s keeping you from running a GOOD homebrew game. Worldbuilding is kind of like sugar. You should never, ever pour it into an engine. Even a game engine.

That’s right. If you’re a worldbuilding GM, Angry is here to ruin your fun and tell you your games are s$&%. I’m sure you’ll want to leave a comment. Just remember that opinions are like a$&holes and if you rub yours in my face, you’ll need a doctor get my boot out of it.

Incidentally, don’t forget to like, share, and subscribe and to support me on Patreon!

But seriously, worldbuilding is a problem. It scares some GMs out of running homebrew games, which are seriously the best kinds of games to run. And it lets other GMs ruin what would probably be a really great game without even realizing they’re doing it. Worldbuilding is a hell of a drug. Fortunately, Angry is here to tell you how to start a homebrew game in a world of your own without having to touch the stuff at all. And you’ll still end up with a rich, detailed, deep, wonderful, living fantasy world like mine.

In a World…

Worldbuilding is the process of building the fictional world in which your game will take place. But it’s important to understand what that means. What a world actually is. To explain that, I’m going to use D&D’s Forgotten Realms as an example.

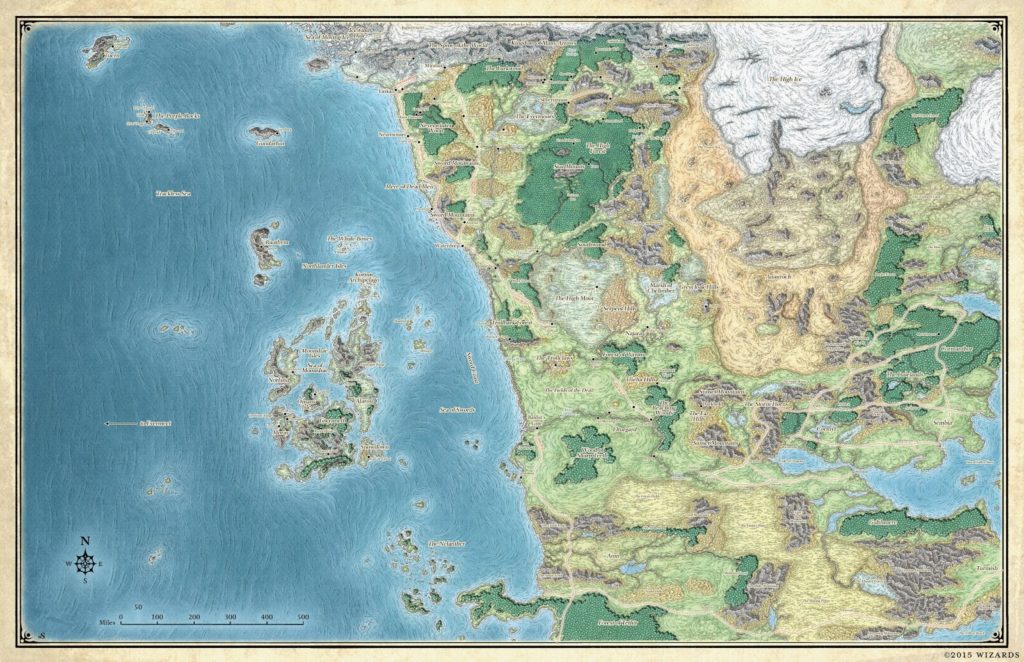

When I say Forgotten Realms, do you picture something like this:

Well, you’re wrong. That’s not the Forgotten Realms. That’s a map of the northwestern corner of the continent of Faerûn which is just one of the continents on the planet of Toril. There’s also Kara-Tur, Zakhara, Maztica, Osse, Anchorome, Katashaka, and the continent-come-lately of Laerakond. Laerakond actually used to reside on Toril’s sister planet of Abeir. Those two worlds keep merging and unmerging again. Kind of. It’s complicated. And Abeir-Toril is just one realm in the Forgotten Realms cosmos. There’s other realms too. And they keep changing. There used to be places like Arvandor and Dweomerheart and the Demonweb Pits, but everything changed and they got scattered around other realms like Celestia and Baator and Arborea and the Abyss. And then everything changed again and they all got scattered across the Astral Sea and into the Feywild and stuff. And also, once upon a time, Earth was out there too. Our Earth. We were part of the Forgotten Realms. Abeir-Toril was actually just one of an infinite number of parallel Earths. Theoretically, if the Avatar took the wrong Moongate, he could end up in Waterdeep.

But all of that isn’t really the Forgotten Realms either. Not all of it. Apart from the continents and planets and planes and all the maps and all the dots like Waterdeep and Myth Drannor and Skara Brae and Cleaveland, there’s a bunch of other s$&% too. Like the extensive-to-the-point-of-f$&&ing-overwhelming list of gods. Which also keeps changing. That’s part of the world too. All those deities are unique to the Forgotten Realms. Except for the ones that also exist in other D&D universes, like Lolth, and the ones that emigrated from Earth, like Oghma.

And then there’s the extensive history of the Forgotten Realms. All that s$&% I mentioned about planets and planes shifting and merging and the everchanging Spreadsheet of the Gods? That’s all canon. There’s vast wodges of timelines that describe every one of those happenings and hundreds more. And with that extensive history comes a whole slew of ancient cities and kingdoms and peoples and races that no longer exist. And thousands of NPCs, living and dead.

And did I mention that the Forgotten Realms setting also has its own set of unique laws of magic that are unlike any other D&D world? Depending on the edition, that is. There’s this thing called the Weave that arose when one goddess ripped off a chunk of her body and threw it at her sister during an argument over who left the lights on in the cosmos. Seriously. And that’s where magic comes from.

And then there’s all the unique races, subraces, classes, kits, prestige classes, paragon paths, and backgrounds that exist only in the Forgotten Realms. I am not even going to go into that s$&%.

All that stuff – the maps, the cities, the gods, the timelines, the NPCs, the laws of reality, and the special rules – all that stuff IS the Forgotten Realms. That’s the setting. That’s the world. Because, when it comes to an RPG, a world is more than just an imaginary physical realm you can put on a map. It’s all the details that have ever been invented about the world and anything in it. And creating all that s$&%? That’s worldbuilding.

Of course, I’m using the Forgotten Realms as my example specifically because there’s a lot of details. And because they’re a lot of fun to sarcastically paraphrase. But you can find a similarly extensive list of details for just about any published world. Eberron. Golarion. Even Greyhawk. And Greyhawk has been officially dead for at least the last fifteen years. And the problem is that, as a gamer, you’re used to that kind of thing. You’ve been taught that that’s what a world is. What a setting is. And the internet isn’t helping at all. Look at Titans Grave or Tal’Dorei. They got the full-on RPG setting treatment despite them basically just being the homebrew worlds some crappy, C-list actors played their personal games in and then narcissistically broadcast those games over YouTube.

So naturally, when you decide it’s time to start your own homebrew game just like your heroes Wil Wheatabix and Mike Mercer, you figure you need a world too. You know it doesn’t have to be as complex and detailed as the Forgotten Realms, but it should be on par with Critical Rollistan, right?

Or maybe it doesn’t have to be. Maybe you realize that even that’s too much for a home game. But you still know you need a world to run a game in. And that means you definitely need a map. And a bunch of gods. And probably a cosmology and some kind of history. And some NPCs and factions and things. And once you start making a list of the stuff you think you probably need before you can run a game, the list just keeps coming.

Welcome to the worldbuilding trap.

The Worldbuilding Trap

There’s two ways to get caught in the worldbuilding trap. The first is to try to build a complex world on par with a published setting because you think that’s the right way to do it. The second is to have a totally awesome idea for the best campaign world ever and then get more interested in building your world than you are in running a game for your players.

The truth is that worldbuilding is almost entirely unnecessary. And if you’re the sort of person who just wants to start running a game, that’s probably good news. It’s a whole bunch of work you don’t have to do. But if you’re one of those people who loves worldbuilding, you’re probably saying, “yeah, it’s unnecessary, but it makes my game better and I like doing it and I’m going to keep doing it.”

Guess what? You’re wrong. Worldbuilding doesn’t improve your game. It wrecks your game. And you’re not doing it because it’s fun. You’re doing it because you’re addicted to your own brilliance. And you’re not impressing anyone.

I want to be clear that the worldbuilding trap is about upfront worldbuilding. It’s about building the world first and then building the game inside it. It’s about thinking you need the world first. Or thinking that having a world first makes for a better game.

Take the Forgotten Realms. Truth is, FR existed for many years before anyone wrote a setting book for it. Ed Greenwood used to write fantasy stories as a kid, see? And they took place in this swords-and-sorcery alternate Earth. And when he discovered D&D, he used that world as the basis for his games. And as the basis for the articles he started submitting to Dragon Magazine. And then, one day, the folks at TSR – the company that published D&D at the time – put out a call for new campaign settings and Ed Greenwood sent his in. And only then, after years of writing stories and running games in that world did the world actually get seriously built.

Eberron had a similar story. Keith Baker entered a contest that WotC held to find new campaign settings and Eberron was his pitch. But some of the details for Eberron came from his work as a writer on a failed online video game. Even Greyhawk didn’t start out as a built world. It was just a ruined castle that E. Gary Gygax was using as the setting for the dungeon crawls he ran his kids and buddies through while testing the first version of D&D.

And then there’s the Angryverse.

I know I have a big ego, but it’s not so big that I’ll compare myself to Gygax or Greenwood. But I did just share a bunch of lore about my world and I knew that I was contributing to the worldbuilding trap when I did. So I’ve got to bring this up. The Angryverse isn’t something I sat down and wrote. It started growing in the summer of 2010 with one tiny detail, one change I made to the default D&D 4E Points of Light setting. I decided – because of my recent playthrough of God of War III that gods maintain the natural cycles of the mortal world just by existing. So, if something happened to a god, the cycle they maintained would fall apart. Thus, when Orcus kidnapped and imprisoned the Raven Queen – goddess of winter, death, and fate – the world got stuck in perpetual autumn. It started to waste away because it couldn’t go through the natural process of death and renewal that winter provided. Oh, also, the dead wouldn’t stay in their graves.

As I ran other games for D&D 4E and Pathfinder and D&D 5E and Savage Worlds and a host of other games, I kept using the same world. And I kept adding more details and changing how things worked. Eventually, I had to work out the nature of life and death and the laws of magic. As I set different campaigns and adventures in different parts of the world, I had to add details about different regions and nations. And as different campaigns demanded different bits of backstory, I had to flesh out the history of the world.

The best settings are the ones that grew organically. They weren’t built as worlds in which to tell stories. Stories were written and games were made and details were added to the setting to enable those stories. That’s why they feel so real. Not just because there’s a lot of details, but because they grew and evolved over time. Like a living thing. People can tell the difference, even if they only came in later.

But so what? So what if the best worlds – like mine – grow slowly and organically over time? That doesn’t mean you can’t build a great world first and put a game in it second. Why not build the world first?

The thing is that worldbuilding is to a campaign what backstory is to a player-character. And I realize that, by saying that, I’m inviting arguments from all the snowflake players who love to hand the GM ten pages of Mary Sue backstory crap. But I’ve already heard them all. I’ve heard the “creative expression” argument and the “it helps me play my character better” argument and all the rest. And no. It doesn’t. But you can’t see it because you’re more interested in writing fanfiction about your awesome character than you are about playing an interactive game with other people.

As I’ve said many times – both on this site and in my book – role-playing is about making choices and dealing with the consequences of those choices. But there’s more to it than that. An RPG is a multiplayer, interactive experience because it’s about human characters and humans are defined by their interactions. And changed by them. When you’re writing a novel or a crappy story for Fanfiction.net, you have total control over everything. But in an RPG, you can only control your character if you’re a player. And you can’t control the characters if you’re the GM. The story of the game emerges as the players and the GM interact with each other through the game world. It’s an inherently organic, reactive, evolving, emergent process. And not just for the characters and the world, but also for the GM and the players themselves.

Backstory – character backstory or world backstory – is about understanding everything that makes the character or the world tick so you always know what they should do in the story. That’s useful when you’re writing a story. Alone. But it’s inherently constraining in an RPG. It keeps you from adapting to the needs of the story and the game and the other players. And it keeps you from being surprised by your own choices, which are the ones you’re most invested in.

I’m going to tell you a secret that sounds like complete, hippie-dippie bulls$&%. Something I’ve learned from running homebrew games for three decades. When you do it right, writing a game becomes an act of curiosity and running a game becomes an act of discovery. And so does making and playing a character. If you have unanswered questions about your world or about your character, you’re actually excited to find out the answers. And if you let them answer themselves organically, the answers can catch you by surprise. If the only thing you know about the Valley of Daggers is that it’s called the Valley of Daggers and you only know that because that’s the name you wrote on the map, you’re as curious as the players to find out what the hell is there. And when you actually sit down to write an adventure that takes the players to the Valley of Daggers, you get a sense of wonder.

No matter how much you tell yourself that you’re willing to change anything you design, the more you decide beforehand, the less you’ll react. The less you’ll pivot. The less you’ll follow a crazy whim. The less you’ll get curious and get surprised. And the world will never take on a life of its own that way. It’ll never feel alive.

And it’ll also never feel real. See, the more you plan your details and make them all fit neatly together, the more artificial and contrived they’ll feel to the people playing in your world. When things fit perfectly and make perfect sense, when there’s never any weird inconsistencies or loose ends dangling around, the world feels like a façade. A Disney World attraction. Now, I’m not talking about plot holes here. Those are a different beast. I’m talking about details that don’t fit together because there’s a space between them. A gap that implies there’s a missing piece. Real-life is messy and complex. There’s always another detail to discover. No one knows everything about reality. And if your world feels like that, it’ll feel real.

So, how do you avoid the worldbuilding trap? How can you start a campaign without a world? Simple. You just put together your campaign like you’re a s$&%y blogger who works for Buzzfeed or the New York Times and calls himself a journalist.

Five Details About Your World that You Won’t Believe

When you start a homebrew campaign, you want to minimize the upfront worldbuilding work – to avoid the worldbuilding trap – and you want to minimize the amount of exposition you shove down your players’ gullets. Because they don’t want to read that s$&%. They signed up to play a game, not to read a f$&%ing setting tie-in book for a franchise that doesn’t even exist yet.

The rule is simple: you’re not allowed to give the players more details than they can count on one hand before the game starts. And you’re not allowed to create more details than you can count on both hands before the game starts. To start a homebrew campaign, you come up with no more than five facts for the players and five more for yourself. That’s it. And when I say facts, I don’t mean paragraphs or pages. I mean sentences. That’s it. Ten sentences. Well, you can have a list or two in there as well. And, actually, two of those facts will have to be more extensive. But those are special. I’ll get to that.

After you come up with your ten facts and you give five of them to the players to make their characters, it’s time to stop worldbuilding and start writing games in the world. It’s time to write your first adventure. As you write that adventure, you’ll probably need to invent some details about the world to make the adventure happen. But keep them short and simple and only invent what you need to run your first adventure. No more. If you want to waste your time building a fantasy world, go play Minecraft or write the f$&%ing Silmarillion. But if you want to call yourself a GM, run a f&$%ing game. Yes. I’m gatekeeping. Oh, horror!

Now, don’t worry. I’m not leaving you high and dry here. Because I don’t want you just inventing whatever ten dumba%& facts you want. There’s a few very specific facts you have to invent to build your world and start running your game.

Fact One: Tell the Players What the Campaign is About and What the Goal Is

If your campaign has a goal, tell your players what it is. Otherwise, tell your players what the game is about and what they’ll be doing. That way, they know what to expect and they can make characters that suit the game. As a rule, never let a player make a character or even think about a character before they know what the campaign is about and what the goal is.

Not only does doing this help the players make good characters, but it also helps the players get engaged and excited. So don’t bury the lede. You might have to be vague and secretive to avoid spoilers, but don’t keep secrets unnecessarily. Everyone knows that Strahd is a vampire. If you’re running Ravenloft – the original GOOD module about Strahd, not the crappy modern knockoff piece of s$&% – tell the players that they’ll be stuck in a cat and mouse game with a powerful vampire lord as they explore his castle and try to thwart his plans. But if the game is about the heirs of an ancient empire trying to seize control of a magical artifact from the player’s homeland that’s secretly the dismembered heart of an elemental titan buried underneath the kingdom so they can revive the titan and take over the world, you might have to be a little more cagey. “An army carrying the banner of an ancient, fallen empire attacks your homeland and, by the end of the campaign, you’ll have to learn the secret history of your kingdom and stop the army from unleashing a cataclysm on the world.” That was one of mine.

Fact Two: Figure Out for Yourself What the Campaign is Really About

Obviously, you might have to keep some secrets about your campaign plans. And this second fact is where you hide those secrets. Like “the heirs of the ancient Zethinian Empire discovered the weather-controlling relic that protects an island nation of elemental sorcerers is actually the dismembered heart of an ancient titan buried beneath the nation and they want to revive it to take over the world.”

If you don’t have any secrets about your campaign plans, use this as another wildcard fact as explained below.

Fact Three: Tell the Players How the Game Starts

You want to tell the players where the characters are at the start of the first game and what they’re doing. Or what they’re going to be doing. This saves some time getting that first session running and it gives the players more information they can use to make characters that fit the game. And it also tells the players what gaps they might have to fill in with what little backstory you actually let them write. If the game starts with the characters escorting a merchant to some distant town, the gladiator’s player will have to figure out why his character left the arena and the wealthy noble’s player will need to figure out what hard times befell him such that he has to take on such a menial task.

And, again, never let the players make characters before they know how the game starts.

Fact Four: Tell the Players Everything they Need to Know to Make Characters

Here’s one of the only times you’re not limited to a single sentence or a short list. This one can be as long as it needs to be. But I’m not giving you permission to fill pages and pages and then hand them to your players. When I say the players need to know enough to make characters, I mean they have to know enough to fill the blanks on their character sheets. They need to know what races and classes and backgrounds and kits and stuff are available and they need to know what level they are and they need to know what optional rules you’re using that tie directly into character generation.

Obviously, there’s going to be some world details wrapped up in this fact. At the start of my campaigns, for example, I point out that I do not allow evil PCs because, you know, I want my game to not be s$&%. And I point out that certain things – like necromancy – are inherently evil. That’s not a matter of perspective. It’s a cosmological fact. And certain character classes need some world details too. Well, they need the names of some world details anyway. Clerics and paladins have to pick domains and oaths and those are tied to the gods of the world. So, when a player says, “I want to play a war cleric,” you have to say something like, “okay, the war god’s name is Marsodin Andrasthorus-Totec. Write that down. It’s spelled just like it sounds. And also, he’s lawful-neutral. Is that cool?”

Now, if you only go over all this s$&% as it’s needed, that’s for the best. Don’t give the players a huge document if you can avoid it. If they’re going to generate their characters by themselves at home, you might have to. But if you can, do it in person and wait until someone actually wants to be a cleric of the god of war before you tell them who that god is. The less you set in stone – for the players and for yourself – the more you’re able to change. Or negotiate. Or compromise. Or pull out of you’re a$& as needed.

Imagine the cleric player says, “well, I wanted to be more chaotic and savage; is Marsin Anderson-Totem my only choice?” You can say, “well, the war god has a savage brother whose more about strength and glory than warfare.” And you can say that even if you made that s$&% up on the spot because you realized an Athena-versus-Ares-style sibling rivalry between war gods might be a cool thing to add to your game.

And you don’t have to give in to everything players want either. You can say no. You can say, “sorry, that’s the god of war; take him or make a different cleric.” That’s perfectly fine. You should never be afraid to keep something out of the game that doesn’t fit your vision. But you might still be able to find a compromise. “What if you’re a disgraced priest,” you might ask. “You can’t control your rage on the battlefield and the clergy kicked you out, but you still have your divine powers and you don’t know why. Maybe Marsodin sees potential in you.”

And that’s the problem with giving players too many lists, by the way. If the only war god is that lawful-neutral one, that player might never speak up and you might miss out on a cool story about a redeemed berserker or a sibling rivalry between the gods.

Keep all of that s$&% in mind, by the way, when you come up with…

Fact Five: Figure Out for Yourself What the Players Need to Know to Create Characters

Before you sit down with your players to make characters, you need to figure out what things are set in stone when it comes to character generation. Like the previous fact, this one can be a hodgepodge of lists and notes, but it still shouldn’t be pages of document. List the races, classes, and other options you’re allowing. Come up with a list of the available deities for the classes that need them. But make sure it’s just a list. Name, symbol, alignment, sphere of influence. And don’t include any gods that don’t have anything to do with character generation. It’s nice if the world has a god of agriculture, but that god ain’t going to have any clerics or paladins, so it doesn’t matter here.

And here’s a piece of bonus advice for you: ALWAYS remove a couple of options from the core rules. Pick at least one race and one class to remove from your game. And if you want to allow options from sourcebooks outside of the core rules, remove options from the core rules to make room for them. Trust me. It’s damned good practice and it prevents you from stupidly opening the floodgate and letting in too many options that weren’t meant to coexist. It trains you to economize. And it trains you to look carefully at whether things actually add stuff to the game or whether they are just options for options’ sake.

And it teaches your players to deal with constraints.

Fact Six and Fact Seven: Tell Your Players Two Neat, Unique, Interesting Things About the World

You’ve given the players three out of the five facts you’re allowed to give just to help them make characters. You’ve told them what the campaign is about, you’ve told them how the game starts, and you’ve told them how to make characters. Now, give them two cool, memorable pieces of information about your world. Things that make your world unique and different and special. And if you can’t figure something out, make something up off the top of your head and figure out what it means and why it’s important later.

I might tell my players that, after the collapse of the continent-spanning Zethinian Empire two centuries ago, the world was plunged into a dark age from which it still hasn’t recovered. And that chaotic, elemental magic infuses the islands of their archipelago kingdom, creating extreme and highly varied environments on each island. Or I might tell the players that Santiem is called the Living City because it’s constantly rearranging and reshaping itself according to some kind of plan and because of the strange accidents that sometimes happen in its streets.

Facts Eight, Nine, and Ten: Figure Out for Yourself Whatever You Need to Figure Out

And now you’ve ticked off seven out of the ten facts you’re allowed. You’ve got three left and they’re wildcards. Use them however you want as long as you keep them down to sentences or short lists. No pages of exposition. If you want to define a specific kingdom or describe a historical event, you’ve got to do it in one sentence. If you want to add a bunch of gods or a historical timeline, you can make a list. Not a list of sentences, though. Just a list. A spreadsheet. A couple of cells per row. That’s it.

Now, if you’re running a campaign with an overarching story and a goal, you might have to use these three wildcard facts to keep track of that plan. You might need an extra fact about the leader of the Zethinian army or the ruling family of the island kingdom, for example. Or you might need a list of major plot points. And that means you might not have any facts left to waste on being interesting and unique and brilliant. Which is exactly how it should be. The most important thing to take from this whole article is that worldbuilding that doesn’t grow out of the events of the game is a waste of f$&%ing time.

Campaign Ho!

With your top ten list of fascinating facts about your world, you’re done. Your world is built. At least, enough of it is built for you to just start telling stories and running games. And that’s the point of worldbuilding. The only point. The world exists to let games happen. There’s no world outside the game.

Of course, you’ll never stop building the world. Or discovering it. It’s just that everything you build – or discover – will come from writing games or running them. When you create a town as part of your next adventure, you’ll invent details about the town and the NPCs that live there. When you deal with some weird question in the game about how two spells interact, you’ll end up explaining something about how your world works. And when you have to pull some world detail out of you’re a$& because the players did something crazy, you’ll be adding that a$&pull to the world. And someday, your world will be as rich and complicated and detailed as the Forgotten Realms.

And that’s why you need a bible to keep track of it.

Very good advice, as usual. I have a question though. I’ve had a campaign setting bouncing around in my head, and I have hopes of it eventually being my “Angryverse”, IE, the setting that I run the majority of my games in. It’s going to be more distanced from the standard sword and sorcery settings, and to come up with that, I stated up a new set of core races. Some of them are alterations of existing races (expanding Aarakocra to have subrace options) and some are brand new.

In terms of this 5/5 system, how would you go about handling new races like this? The PHB has cultural backgrounds and the like for each race, and that’s obviously unrealistic for a fledgling homebrew project, but I don’t think my players would like being handed stat sheets without any background info besides ‘This is a race of rock people’.

Tangentially related, would you consider a large, sweeping campaign or several unrelated adventures to be the best introduction to a new setting like this?

I’ve got some great results by handing players a set of stats and saying something like these are rock people. Then answer only the questions asked. Sometimes the answer should be “What do you think?”

Sometimes the results have to be changed later. Reread Angry’s post and notice how common that is, then if it’s needed make the change. And tell the players it’s changing and maybe why.

If you’re adding new races, basic information about their culture would likely be part of Fact Four. It’d be wildly unnecessary to write paragraphs of history, but fit for purpose to say something like, “this is a primitive race of cheerful rock people who are a manifestation of spent magic.”

To sell me on a race, give me 2 evocative sentences and some flavorful mechanics. A whole cultural background would bore me to bits. I Might nonetheless give your game a try if I like you.

I imagine a new race/species/ancestry/style of dress falls under Fact 4/5, and the best way to handle it is to give them 1 or 2 Neat, Unique, Interesting Facts as salespitch and make a statblock only if anyone cares to play them. Otherwise, you can delay sorting that stuff out for later, when and if it becomes relevant.

On your second question, I think the whole point here is that you should not see adventures or campaign as an introduction to as setting. You introduce a setting so campaign and adventures can take place.

The question of a large campaign or unrelated adventures is in my opinion best addressed by taking into account other factors: players availability, preferred play style, how important is overarching narrative, how long and regular is everyone commitment… Once you’ve sorted this, in my experience, you can both have rich setting in “adventure of the week” form of play or in a year-long campaign.

Adventure of the week format allows for more diversity and freedom, so you can show many different places and times in your world. Long campaigns are more focused, so you will more often show a few small chunks of your universe, but they allow to go deeper. I’ve had lot of fun with both, and the necessary amount of setting work looks pretty similar to me.

Thank you angry, this article was really intersting. Another one where you have put words on things I didn’t know i’d aggree with.

In advance, sorry for the bad english.

If I can add something, I’d say that one don’t have to have is own setting to homebrew his game. For example, I play in the Warhammer fantasy universe but i always say “my world” when I talk about my games. Because, I use the Warhammer setting to not having to bother with worldbuilding but when the first has took place, the setting was forever changed. As you said by the player and I. And now, some homebrew campaign later, even if the geography, the gods and magic are the same, the world has changed thank to several PCs actions.

The joy of homebrew without the headache.

This is interesting. Warhammer 40K is a visceral, archetypic world which (on first glance) doesn’t seem to be a promising space for world building.

But authors like Dan Abnett and Chris Wraight do a great job of inserting novel canon into their 40K novels.

I’m particularly thinking of Abnett here: Gudrun, Woe Engines, the Sept, the (badly named but cool concept) of Ennuncia, the malignant Cognitae, and so on.

We as GMs could do the same – especially in Inquisitor-style games.

“When you do it right, writing a game becomes an act of curiosity and running a game becomes an act of discovery.”

This is TRUE and it is GOLD DUST.

This ‘just-in-time’ world building works like alchemy, when it does work. You create – or rather, discover – just enough ‘World’ to support the current scenario and no more. This includes dropping tantalising clues to the players to whet their appetites about future discoveries.

Be sure to record the details (Angry’s ‘Bible’), and when you create apparent contradictions with earlier items, do just enough work to resolve them.

Done correctly: this can give your players a sense of wonder.

Which you *share*, because you also don’t yet know what’s so special about the ‘Valley of Red Stars’ or why the party need to fear the “Lament Configuration”. Or why those cultists were chanting “The Knives, the Knives, The King of the Knives”.

(This agile approach to your World shouldn’t be confused with ‘winging’ a session. Always come to the table knowing what you are about to run. In fact: just-in-time, just-enough world-building frees you up for your main job: building adventure).

I’m curious- what’s the dislike for Curse of Strahd?

I’ve run it a few times. Personally, the ‘stretch’ across Barovia makes Strahd look like an errand boy running all over the place, dilutes the core experience of running around a castle with its master on your heels, and in general, none of the new locations really felt powerful, evocative and appropriate enough to deserve doing the above.

Also, and this is a personal niggle, but the Amber Temple kind of goes a little too far with specifying what the Dark Powers are, as well as involving them directly at all.

It just has a punchier feel when you’re stuck in an isolated castle, with no immediate, obvious allies, needing to protect a lady while finding several hidden powerful artifacts and this extremely powerful, intelligent and handsome man wants to have fun. Over the course of a few hours or maybe a day or two.

As you can imagine, that experience loses potency when you have allies, spend several days or weeks, several comical bumbling idiots, define other, greater evils, a siege that clashes with the core narrative of Strahd the spooky boy and the literal boxes of vampire spawn.

Sapphire, thank you for this review. Very useful.

I’m going to assume Angry is in my Drive folder, because this happened to me and I got to a similar-ish inclusion. See, I was working on a world document, then I was like “I might as well write an adventure for it” and quickly realized how little all I wrote was even remotely relevant.

And with this, you know what. I’m going to do that. I’m going to let this world build itself. Grown like a tree, instead of build out of woodpulp.

Could you suggest a good way to organize/track worldbuilding as it happens over the course of the game? When I have tried this in the past, I wind up with a lot of notes that aren’t well organized so I can find it hard to ties things together.

I linked my article about Campaign Bibles at the end of this article. That’s what they’re for.

I completely missed that. Sorry.

I recommend that you use a format that allows you to throw down ideas and then move them around.

My personal favourite is a MIRO whiteboard. These are free for the 1st three boards. Just google “Miro Whiteboard” to find the site.

Miro can be used to create a slowly growing mess of different coloured Post-It notes, each marked with a little idea. Things like “The Ring of Winter” or “A series of Brutal Murders” or “Ape with Rainbow Wings”. Anything that occurs to you.

You can then shift these about and so group concepts together.

E.g: you might have little areas of your whiteboard tentatively marked “Timberwolf Village” or “Zarda the WitchQueen” or “What’s in the Glacier Tomb?”

Then you create/move your Post-Its into those areas, rapidly forming/reforming areas of coherence.

It works best if you keep it messy. Only be tempted to organise hard little knots of Post-Its once the facts on them have been revealed to players – and thus become immutable.

Hope this is helpful.

I should add that if you do use Miro to help build your game, then do use some visual technique – such as grouping or recolouring or flagging – to indicate which concepts have become fixed/revealed to players.

These become part of your Bible. These are the bits that have to be kept Consistent, and that have to Cohere with other fixed pieces.

But on the same page there are other, lighter-coloured Post-Its with ideas that are just floating around at the periphery. These ideas haven’t yet become (and may never become) embedded in your game.

As you re-read your Whiteboard between sessions and spark new ideas, these ideas orbit in a sort of ‘Creative Zone’, like rocks in a far-distant Oort cloud, ready to sweep in and bring doom to your players.

“If they’re going to generate their characters by themselves at home, you might have to. But if you can, do it in person…”

Last year there was half an article about how being present for character generation was a last resort for the desperate DM. Why the change?

What change? I stand by what I said.

Do a session zero, tell them what they need to do/know and then send them off to do char gen by themselves. If they don’t want to do a session 0, then send them the document. Is what I’m guessing Angry is saying to do, and if so, as Angry says, there is no change.

Excellent advice (of course). The whole point of calling RPGs “cooperative storytelling” is that the GM doesn’t know the full story. As a GM, you setup the basic foundations and let the players help build the rest with you. Otherwise it’s not cooperative storytelling; it’s just storytelling with some randomization (assuming the GM doesn’t fudge the dice rolls).

You sound jealous of CR

Hey! I may not be as successful as Critical Role and I may not be as well known as Critical Roll and I may not be as good looking as Matt Mercer, but I have no idea how to end this sentence.

I need a drink.

Oh man, first the Futurama reference, and now this. Lols were literally had. Thanks Angry!

I’ve no problem with the angry Angry, but I admit sometimes you write things that feel more mean than angry, and it rubs me the wrong way. And for me, the CR comment felt mean and a bit out of place. I hope you see the distinction I’m trying to make here.

It’s not my place to be mad about it, but I thought maybe it was worth pointing it out. Otherwise, great article.

You gotta read the sarcasm. The point is there isn’t anything special about those settings.

It’s fine. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion. And, while I will leave critical comments up precisely because of that, I’d really prefer the comment section not turn into an argument about the perceived shortcomings in my writing style. So just let everyone have their say and leave it at that.

By the way, I guess everything you said here is also true when running something from a published setting. I assume it’s easy to get lost trying to read everything you “need” to know about the Forgotten Realms before even trying to run a homebrew adventure in it.

Also, I’ve found existing setting are a great way into homebrewing. In fact, I’ve found if you get into a published setting with the minimalist approach you’re exposing here, you’ll naturally adapt, tweak and improvise things until you start building your own version of it. Which is exactly how huge settings like the Forgotten Realms organically became such huge sprawling universes in the first place.

My friend commissioned me to make a fantasy apocalypse setting in sunny radioactive California for PF2, and I will be using this article and the 5 god conflict one to design it. It makes my job a whole lot easier, I got to say.

Having said that, I’m going to dissent in part. Since Angry didn’t differentiate between a home setting for a system and a home system with it’s own setting. Games like Call of Cthulu and Anima are great (imo!) because games made with a specific setting are better than generic game engines to make your own. For example… a world where magic runs like blood, everything (classes, point buy, abilities, or skills, or WHATEVER) would be tied to your health and magic. Your going to have to explain that and it won’t fit in a few sentences, since it permeates everything and that makes the entire system better when it’s well thought out.

tl;dr If you want to suck yourself and write more, make your own system that reflects it.

Having said that, this article still applies even then! No one wants to read about the 69 elven kingdoms, they just want to know whether your elves are hipsters or assholes. Keep in mind Angry’s 10 (7?) things when writing a PHB. If your PHB looks like the simarilian and is twice the size, stop.

Maybe, I’m an idiot and missed the point here, in which case come yell at me Papa Angry. 🙂

(The thing that shall not be named got my internet, so sorry if this is a double post.)

This article seems to be focused on a much smaller project than you seem to be talking about. He’s not saying this is how you write a whole new RPG system like Call of Cthulhu or Anima, but rather how to start an adventure campaign within that system. If you’re hacking an existing system to the extent that you seem to be implying, I think you’ve stepped outside the scope of this article.

That said, you’re right about the main gist of this article: only write what you *need* to write adventures and play games, and let the rest just grow as you write and play games. Even something as huge as a whole new PHB or entirely new system! It’s almost as if Angry has some kind of first-hand experience with creating a new RPG from the ground up… 😛

That author is one of the most annoying know it alls I have seen in a long time. Some advice is good but he really missed the mark with self proclaimed “my way is the right way and your doing it wrong” attitude. I wouldn’t purchase a thing this self bloated egomaniac wrote.

I assume that when you say “that author” you mean me. And while I am quite annoying and while I do really do it know it all and while I am an egomaniac, I take umbrage with “bloated.” I am not bloated. I am not filled with fluid or gas. My rotund figure is due to one hundred percent visceral fat tissue. I prefer to think of myself as a “corpulent egomaniac.”

If he wants to be a public commentator, he does need a thicker skin. Keeping an ad hominem attack that adds nothing to the conversation is a good step in that direction!

And while I will continue to do so – and join in the fun – I would ask that we not turn them into conversations. If someone wants to insult me instead of engaging with the ideas fine. I’ll let that stand because I’m a big boy and I don’t dish out what I can’t take myself. But, I’d also prefer not to have that crap turn into threads that get in the way of the people who use my comment section to have useful discussion.

In short, let the thread end here, thanks. Because I do make it a point to keep my comment section clean and clear for people who want to have useful discussions and I will have to start deleting this crap now.

I particularly enjoy reading articles of yours (like this) where I find that I concur in part and dissent in part, because it helps me understand my own thinking about gaming. Having a well-thought-out and well-expressed opposing (or partially-opposing) opinion throws a light on things I haven’t even thought to look at. And as always, an enjoyable read (but I appreciate sarcasm). Thanks.

This is how I homebrew, and I highly recommend it. Make the world as simple as possible to start, and then just let it grow organically as the players explore and render new areas, and let their backstories affect its lore. The constraints that come from letting it grow from the bottom up like that make for much, much richer settings than a single person can come up with just thinking and writing a personal novel about.

I probably went a bit too far with my first homebrew game. I tried to mimic Angry’s structure from his “What Lies Beneath” campaign document from his stash. I thought I did okay – there was 1 page of world info, 1 page of assumptions, admittedly lots of pages about the races and such, and that was it. Though my players were like “oh that’s a lot” so I maybe I would have been better off just making one page with bullet points.

I’m going to guess where I went wrong is that Angry-style campaign documents are suitable for veteran groups, whereas mine are almost all new to roleplaying.

Lesson learned for next time. Thanks, Mr. Angry!

I set up my homebrew by telling my players

“Imagine that you’re playing in Greyhawk. Not the canonical Greyhawk with the map, but the wondrous, undescribed world lit with a golden light that you inhabited when you played DnD as a teenager.”

“You are riding along a muddy track, alongside the toxic mineral spoil-pits that surround the company town of Diamond Lake. You are going to meet your old friend Charg Whitebeard at the Hungry Badger. He has sent word that the Cacogen Cult is at work in this dismal mining settlement. As you ride; you pull out his letter and re-read it …”.

I.e you just conjure enough of the wider world to reassure your players that there is a world there, and then immediately focus on what they need to know for scenario #1.

And in scenario #1 – in this case an adaptation of Paizo’s Diamond Lake – and in every scenario after that – you reveal more of your world to them. And – crucially – you only write enough new bits of world to support each new scenario.

Huh, I just read part 4 of ‘Start and Plan your own Campaign’: and Angry’s concept of a *non-setting* exactly encapsulates how I eased into my current homebrew.

I’m impressed by the clarity of part 4. Why did I read part 18 before I read part 4? Because I have serious mental issues, that’s why.

I just started a homebrew campaign and it looks like I was on the right track at least. Minus the clear structure presented here though.

I tend to come up with a lot of “ideas for facts about the world” in my head and then shelving most of them until they become relevant. They just pop into my head as my brain tries to make sense of things I guess, I’ll see how constricting they become as the campaign progresses

It feels strange for you to so blatantly call out certain people in the TTRPG community, when much of their own advice is similar to what you’re touting here. I know you’re the ANGRY GM, but c’mon. Seriously?

Is this the first article of mine you’ve ever read? C’mon. Seriously?

In earlier articles you have said that playing a sandbox campaign requires a lot of preparation. I had assumed that meant world building–deciding regions, populating them with zones and rosters as per your other articles. Could you clarify how to synthesize that advice to the advice in this article?

Here’s my experience: if I have to whip some detail out of my head and leave it at that (the primary religious ceremony at Marsodin’s temples is simulated combat), great. It’ll simmer in my head over the next week, and maybe we can do something interesting with that later in the adventure.

But if the players want to attend one of these ceremonies, and I have to come up with what the place looks like and what the priests are doing and saying and wearing, and figure out how this is leading to an interesting story on the fly, I’m going to be stumbling over my speech and just generally making a mess of things.

So all the plot details the players can’t interact with are fine as a great fog: I can say anything I want about the distant island of dreams because if the players set off the moment they hear about it, they aren’t getting there this session. But the characters and locations they can reach this session I need to feel comfortable with. And with a sandbox, that might be 9 parts paths the players don’t go down, to the one curveball tangentially related to my preparation they do come up with.

I’ve been noticing a lot of campaign primers that people have been posting on the internet. One that I was looking at from a GM I like was originally 14 pages and the revised was 21. They were saying that this was the handout they gave their players before the start of the game. This seemed ridiculous but everyone chimed in on how theirs was longer or how much they loved it that I felt that I must be doing something desperately wrong. So, yes, I was: I wasn’t doing anything at all and just hashing out stuff like races/kingdoms/gods/etc during a session zero. Having certain limitations really fuels creativity and stops the indecision that players get and also helps explain the plot. Now our assignments should be to go through all the steps and post our results so we have magnificent examples.

This is basically how Tolkien did his worldbuilding. He didn’t start with a map and notes on every nation and their history and then come up with a plot – he wrote his plot and invented details as his characters went places. Whole nations with thousands of years of history popped into existence when he tried to figure out who this ranger guy Frodo met at the Prancing Pony was.

Tolkien is also a great exemplar of how – even very humble ideas – can lead to greatness. What modern authors sometimes refer to as ‘scaffolding’ – ideas that help build the structure, but that are removed in the final product.

As Tolkien was creating the book (at a very primitive stage) one of his ideas was that Gandalf would ride up to the hobbits (as they were hiding by a lane hoping to surprise him) and then ‘sneeze’.

Then Tolkien changed it to a ‘sniff’.

Then (apparently) he was inspired to change the horseman from Gandalf to some Rider who was sniffing out the hobbits.

Then he imagined what kind of Rider would turn up and start ‘smelling for’ the Hobbits.

That intriguing concept – a Rider on a horse who is nevertheless trying to track you by smell – led the genius Tolkien to the Nazgul.

Plausibly (I dont know enough to be sure) the idea of the Nazgul then led the coherently-minded Tolkien to the whole structure of the Nine Rings, the Three and the Seven – logical extrapolations from Ring-enslaved Humans as ported across to Elves and Dwarves.

I can’t remember if the idea of the Ring came before the Riders, or afterwards – perhaps someone else can chip in.

Thank heavens Tolkien wasn’t a GM working to a tight deadline.

Or else Frodo would still have been called “Minto”. And Aragorn would have been “Trotter”, the tough-but-tortured hobbit with wooden feet.

What if we already have a fairly detailed setting? Would we use the five player-side facts to introduce it in the same way?

I have a setting I’ve been creating for around five years now, based on realizing that a couple previous games I ran could fit together into one world. Now, it has gods and nations and languages and a history that I add to regularly. I will admit, I do enjoy worldbuilding as a hobby in and of itself, but I do try to keep the setting loose enough for both games and short stories to emerge freely. Is even this too much?

As much as I love world building, even more than running games if truth be told, I have to agree that it has never once actually improved a game I’ve run. In fact my world-building worlds and my game worlds are entirely different for just that reason

A finely tuned world-building world can almost never survive contact with the players, and most players couldn’t possibly care less about all the cool stuff you think you’ve created anyway, it just gets in the way of their fun. I call it being “lore-locked” and it’s poison for a game (or game character for that matter)

it’s best to just sit around with your other world-building friends and build worlds than ever try to play a game in one

That said, a lot of my game encounters are loosely built around events that I have established in my world-building worlds, doing this affords me the ability to easily add verisimilitude to my descriptions through intimate knowledge, but removes my vanity from the actions and results of the characters as they destroy months, and years, and decades of lore I have worked hard to establish

Pour your heart and soul into the worlds you create for yourself, it’s an enjoyable hobby. But independently pour your heart and soul into encounters for the games you run for others

If you want to literally play worldbuilding with your friends, there’s an interesting RPG for that too! It’s called Microscope by Lame Mage Games. Literally allows you to construct a history of a fictional universe with a few friends.

I have to agree about the character background bloat as well. My last PC was a “Huge gladiator who worshiped Odin” (Cleric, not Barbarian) Everything else would have to be discovered in game. And it was so much fun because even I didn’t know what was going to happen.

My dragonborn fighter is apparently a half-decent cook and a fantastic flutist since I needed to pick a tool proficiency from my class and an instrument proficiency from my background. Not my fault I haven’t rolled less than 20 on flute checks -_-;

Interesting. I’ve run a lot of short campaigns in Mystara, and a few in Forgotten Realms, but my last was home brew.

Running Mystara in particular, but also with FR to a degree, I could drop in my own adventure into a world I’d repeatedly skimmed through various Gazateers and other world guides splat over the years. I had the confidence to make up what I needed to because I had the big picture framework in my head already, so the new details were just hooked in. Maybe the key was the skimming? Knowing the lay of the land, but not enough to get in the way? Regardless, the framework helped, it didn’t hinder.

Whereas with the home brew, for a long time I’d make stuff up then forget it, even though I’d log it. Because it didn’t properly connect to anything in my head. It wasn’t until after I’d been running it for a couple of years that I had a solid big picture framework to expand on.

I agree – I thought for years that I’m better at making up stuff within a created universe than striking out on my own. That said, Angry’s guides to building worlds and in particular the solid direction on adventure templates are persuading me to change my mind, sack up, and try doing a homebrew world.

In passing, his ‘five gods’ system I find works great in the Forgotten Realms, simply because, with that vast panoply of gods in that setting, there is pretty much guaranteed to be a god who’ll fit any two thematic concepts you string together, and if they don’t, you can fudge it a bit by saying that one concept is an aspect of an established god. In one of my campaigns, I’ve linked the concepts of retribution and tradition into Chauntea, the goddess — linking into the idea that nature follows ancient and immutable laws (tradition) and that the earth eventually pays you back for the wrongs you do it (retribution). In this particular part of the Realms I’ve based the story in, therefore, people worship a younger, more primal version of Chauntea: she is still goddess of harvests and agriculture, but she’s closer to her old Earth Mother or Great Mother form, a goddess of huntsmen as well as farmers.

But the ‘five gods’ system mainly works because it allows you to pick five deities out of the hundreds in the system to focus on and allow the rest to fall into the background. Those five gods then become the main deities of worship in whichever back corner of the Realms you set your story in. The locals might worship any number of gods, but your prominent churches are of these five, and your prominent NPCs are more likely to be worshippers of these five. It allows you to put together a group like Chauntea, Helm, Gond, Savras, and Lathander and it all works.

In the article that Angry links at the end of this one, he recommends that you skim through your campaign bible on a regular basis, with the end goal of just familiarization and letting different bits bounce around in your head. I imagine the ultimate effect of this browsing will be the same as what you got from browsing the gazettes and guides for Mystara and FR.

Pingback: He's Alive! | Dungeon Master Daily

I’ve just recently stumbled upon your site while trying to solve a problem with a player. Player Agency… God how I hate that PC crap.

Anywho, as for this article, I too have a very old campaign that i’ve continued to work on over the past 20+ years. The one thing I do in it that I have not really seen in any published works is that it is a living world. Meaning, just because the players are 3rd level, that dark forest over there is not going to suddenly be filled with monsters around their level. If there is a Big baddie who calls it home, and the players (due to player agency crap) go into it without bothering to learn anything about it, and run into Mr. Big Baddie. Well… all I can say is that when they roll up their new characters they should probably try to remember not to be stupid like that in the future. The world is not a static place exactly so just dont be stupid, think about what you are doing, before you do it, research stuff, and make a plan. Fail to plan plan to fail. Oh, I think I may be the first person to come up with the term “DM Agency”. If not, *shrug* DM’s Lives Matter!

… I’m sorry to burst that last bubble.

https://theangrygm.com/i-am-a-free-agent/

Oh that is awesome. Oh well. But dam it felt good there for a second. 🙂