Welcome back the Megadungeon!

We’re going to have a change of pace today. It’s kind of a fluffy week here at The Angry Dome. We’ve laid out a lot of crunchy stuff for our megadungeon. We made spreadsheets and encounter budgets and we talked about structure and gating and critical paths and all sorts of meaty adventure design stuff. So, time to start building the damned dungeon, right?

Well, we could. If we wanted it to kind of suck. And to fail at its goals.

Remember that one of our goals with this project was not just to create a dungeon that was a fun mechanical challenge, but also a dungeon that told a story. And one that told a story through its environment. Well, primarily through its environment. If you look at back at some of my strongest Metroids. I mean Dark Souls. I mean influences, you’ll notice that a lot of those Darks Souls. I mean Metroids. I mean influences. Influences. They tell a lot of their story through their environment. Oh, sure, there’s things to interact with too. Metroid Prime had its scanning mechanic. Dark Souls had all those videos that VaatiVidya made. I mean, Dark Souls had its NPCs and that cutscene at the beginning. Bioshock and Arkham Asylum had audio logs and expository NPCs.

The point was, though, that the site had a story. And part of the fun of playing the game was discovering that story through gameplay. However you did it. And the less exposition, the better.

So, we’re going to talk today about the fluffy side of the adventure.

Backstory, The First Act Problem, and Where Video Games Fail Us

First of all, let’s talk about story. Because story is a word that people throw around a hell of a lot. And most people use it wrong. I’ve talked extensively about the role of story in RPGs. And I don’t want to repeat myself. This series is meant for the people who’ve got my basic stuff down, after all, and want to see an advanced project. Something big and hardcore. So I’ll just remind you that the STORY of an RPG is the GAME ITSELF. Just like the STORY of a MOVIE is the MOVIE ITSELF. Story is the entire thing and all the parts of it: plot, narrative, characters, setting, the choices people make, the conflicts, and resolutions, the climax, the denouement, everything. The story is what you are experiencing when you play the game.

Now, the thing is, we’ve talked about how the environment needs to be an active participant in the story. We want the environment to change in response to the players’ explorations and interactions with it. The setting itself is a character in the story because it responds to the players. When they break open some cursed door, the setting gets flooded with undead demon elementals that they unleashed. When the open the flood gates, they expose some areas and flood others. In that sense, the setting is part of the story. But that’s actually not what we’re talking about here. Because that sort of s$&% is more a part of the mechanical design of the adventure. That stuff will happen because we’re planning out how the settings responds to the players.

But, when I’m talking about story NOW, I’m talking about something different. I’m talking about backstory. And, if you want to get really technical, I’m talking about the first act. Let me explain those technicalities.

First of all, backstory is all of the crap that happened before the story that created the story. In Metroid, for example (the first one), the backstory is that some scientists discovered an alien creature and were shipping it back to their lab for study. But then, the space pirates lead by Mother Brain, Ridley, and Kraid, attacked the scientists and started breeding the aliens as a weapon in their base on planet Zebes. Well, that’s one part of the backstory. Because there’s also backstory about a mysterious bounty hunter and the Galactic Federation’s failure to deal with the space pirates that lead them to create a team of elite bounty hunters called the Space Hunters. And also there was a mysterious alien race that left Artifactor Statues around Zebes that have mysterious weapons and superpowers hidden in them.

The point is, all of that crap leads up to the start of the game when Samus Aran, Space Hunter, arrives on planet Zebes and starts gathering space artifacts, kicking space a$&, and taking space names.

Okay, that’s backstory. Every story has backstory. Because, the thing is, every story has bits that are important BUT boring. All that crap about the Metroids and the Artifactor Statues? It’s cool and all, but it doesn’t make for an exciting game. The exciting game stuff starts when Samus arrives to kill space pirates.

And every story struggles with how to share its backstory. See, in the end, it is kind of important to understand the backstory. Without it, the story loses some of its context. It might not even make sense. “Who is this robot named Metroid and why is he killing those spikey dudes and what is with the weird bird statue with the freeze ray in it and holy s$&% why is there dragon now?” Metroid (the original) revealed its backstory in the game manual. There was a little written short story that explained it all.

Then, there’s Super Metroid and Dark Souls. Those two games reveal their backstories by making the player watch a little video sequence at the start of the game. “The last Metroid is in captivity, the Galaxy is at peace…” “In the Age of Ancients, the land was unformed…”

And then, there’s Metroid Prime and Portal and Bioshock. Those games dump you into the action with no real preamble. You respond to a distress call, go explore this spaceship. Your plane crashed, welcome to Rapture. “Hello and Welcome to the Aperture Science Enrichment Center.” Instead, those games rely almost exclusively on revealing the backstory to you while you play. Whether you’re scanning computer logs to piece together what happened on Tallon IV and what the Space Pirates are up to or trying to disentangle who GLaDOS is and what those scribblings on the wall mean or whether you’re listening to phonograph recordings while Atlas fills in the details, as you play, the backstory is revealed to you.

That’s backstory.

But there’s another issue with interactive media like video games and RPGs. There’s also the issue of the first act.

Most movies and TV shows and novels actually start a little bit BEFORE the action gets going. Or, we see things get set in motion and then the story kind of pauses. Take, for example, Lord of the Rings. I’ll use the movie, Fellowship of the Ring. We start with the expositional backstory. And we see the forging of the One Ring and the defeat of Sauron and the day the strength of men failed and how Gollum got and lost the ring. All the stuff that conspired to put the One Ring in the Shire so we could get on with the damned story.

But then what happens. Well, then we meet Bilbo. And we get to see the life in the Shire. We get to see how Bilbo and Frodo live and how happy they mostly are. In short, we meet the main characters and get to see a little bit about the life that is about to get completely d$&% over because they are going to become protagonists.

In storywriting parlance, we call that first act. Because most stories conform to this thing we call a three-act structure. The first act, the first part of the story, usually introduces us to the characters and the world and their relationships and ends when something happens to kick the story into motion. Often, a lot of backstory also gets revealed in the first act. The second act involves the heroes dealing with the thing that started the story and facing challenges and having experiences and, you know, all the good stuff. The second act generally ends at a low point. S$&% goes bad. The story gets really serious. And now it’s a f$&%ing emergency. The third act involves the climax of the story and the denoument. The part that comes after the climax to let us see how everything works out.

Most of the story happens in the second act. The first act is setup. The third act is conclusion. So, in Fellowship of the Ring, the first act is all that “Concerning Hobbits” crap and it ends when Frodo and Sam set out from the Shire. The second act is about seventeen goddamned hours long. And you can argue that ends when Boromir tries to take the ring and the Fellowship falls apart, forcing Frodo to realize he has to go it alone. At that point, the orc army attacks and that’s the climax of the movie. But, the thing is, some folks argue that Gandalf’s death is really the end of act 2 and everything after that is climax. It’s fuzzy. But you get the basic point.

Now, here’s the problem with interactive media. Three-act structures suck for interactive fiction. Why? Because the first act is usually boring as s$&%. And, honestly, some movies dispense with the first act. This leads to a Latin term called “in medias res.” The phrase literally means “into the middle of the thing.” But what it generally means is that the story is skipping the first act. We’re starting with that thing that kicks the story into action.

BUT…

The thing is, the first act IS important. In addition to introducing characters and relationships, it also helps us ease into the setting. Basically, it’s like wading into the story instead of plunging into the deep end. And the more extreme the temperature in the pool (that is the more complicated or intricate the story), the more important it becomes to ease your audience in. So, you CAN’T actually just skip the first act. Unless you’re trying to do something artsy and unique. And sometimes that works, but most of the time it bombs and people notice.

So, anything that begins “in medias res” still has to share all of its backstory AND all of its first act stuff. It just has to find ways to work them into the story as they become important.

Again, let’s go back to Metroid Prime. There’s two relationships that are extremely important in the story that would normally be part of the first act. Samus’ relationship with the Space Pirates (they are mortal enemies) and Samus’ relationship with the Chozo aliens (basically her adoptive parents and mentors). So, as Samus explores the derelict spacecraft at the start of the game, two things happen. First, she encounters Space Pirates (which are identified by a Bioscan) who are immediately violent toward her even though they are injured and dying. They were screaming a distress call for any help because monsters had destroyed their ship and, when they see it is Samus who has responded, they literally die trying to kill her. Some of them can’t even stand up, but they still shoot her. She also encounters logs in the ship that talk about how Samus destroyed their base on Zebes and ruined all their stuff and how she’s the worst person in the universe. Later, when she encounters the pirate leader Ridley and he escapes, she makes this frustrated and angry gesture. A visual “dammit, I wanted to kill that guy!” So we know there’s bad blood there.

Now, where things get really interesting in tabletop games is that there’s actually TWO first acts. One of them, we’re not worried about. It will work itself out. And that is the establishment of the heroes and their relationships. We will meet the PCs as they play the game and we will learn about their relationships and backstories as they play the game. That part happens naturally. Usually, the players just sort of do it.

But the other part of act one is establishing all the stuff that isn’t under the players’ control. Who are they IN THE WORLD? Why are they doing what they are doing? Who are the other characters in the world who are important? Fortunately, the most vital parts of all of that crap tends to be handled during character generation or in the introduction to the game. It’s part of the premise of the game and GMs and players handle that.

In that respect, we have it a lot easier than video game designers do. We can start in medias res and most of the first act crap works itself out during character generation or because of the unique aspect of RPGs where the protagonists are free willed and interact on their own as they wish.

Hence, most RPGs aren’t actually three-act stories. The three-act structure is far, FAR less useful when planning an adventure than most GMs and RPG designers actually realize.

In the end, when it comes to designing a good adventure then, we really only have to worry about the backstory and about designing the actual adventure. And because most adventures are designed to start with an inciting incident or hook and end after a climax and resolution, it’s not even really useful to think about the adventure in terms of three acts. Instead, we figure out the backstory. We build the adventure with a beginning, a middle, a climax, and an end. We seed the adventure with the backstory. And the gameplay will handle everything else.

Story Informing Gameplay and Vice Versa

What’s really interesting though is that, from a certain perspective, the backstory doesn’t have to matter. We could, in theory, get away with a very bland backstory and the adventure would still be enjoyable for lots of people to play. “Once upon a time, dwarves made a city. Now orcs live there. And they worship a lich and he lives in the bottom of the city. Go plunder the city, kill the orcs, and get rid of the lich.” Done and done.

But that won’t work for us. Because we want the environment’s backstory to be part of the game. That is, we want it to be part of the reward for playing the game. Dark Souls gives us a good example of the dichotomy because it is a game with both zero backstory and piles and piles of backstory.

You could play Dark Souls from beginning to end without ever understanding anything but the most basic elements of the story. Kill the four gods, save the light, you win. The game doesn’t care if you understand the backstory. The game doesn’t give a s$&% if you realize that the crow is probably Velka, the God of Sin, and why the Firekeepers are doing their thing, and that Solaire might be the son of Gwyn and that Anor Londo is shrouded in an illusion, and how the Furtive Pygmy probably created the whole undead curse or maybe not, and what the Abyss is all about. The stuff is there if you want it but it doesn’t matter if you don’t have it. There’s two separate experiences. Learning the story and executing the game.

On the other hand, take Arkham Asylum. You literally can’t miss the story of Arkham Asylum. Which is good because the game would be gibberish without it. I mean, you can argue that Dark Souls is gibberish without the story, but Arkham Asylum literally doesn’t work without the story because the story keeps driving everything you do. Without knowing who Scarecrow is, the Scarecrow sequences would be complete, bizarre nonsequitirs. The fact that Bane is the source of the Titan helps you figure out that you need to fight Bane the same way as the Titan mutants. When Poison Ivy goes berserk because the Joker infected her with Titan, the entire environment changes. Her plants grow to block off some areas and destroy others. And they only die when Poison Ivy is defeated.

Metroid Prime falls somewhere between the two. You can ignore a lot of the story of Metroid Prime, but some bits and pieces force themselves on you no matter what, like the Chozo Artifacts, the cleansing of Flaaghra and the ruins, and so on.

For a more extreme example, look at a game like the first Super Mario Brothers. In that game, there IS a plot. Plumber pulled into Mushroom Kingdom, Princess kidnapped by dinosaur-turtle, subjects of kingdom transformed into rocks and trees. But the plot is entirely superficial. It’s an excuse for the game to happen. There literally could be anything at the end of the path and it wouldn’t change the game. Bowser could have stolen Mario’s favorite plunger. Or his car. It’s all the same.

We want the Arkham approach. We want a game in which the story and the adventure work together. A game in which it is very hard to ignore the story. One in which the backstory keeps getting in the way of the characters, even if the characters try to ignore it.

But that makes life much harder for us.

Multitasking

Here’s what all of this means for adventure design. Because I know you’re all begging me to make a point by now instead of pontificating about story in games. Well, here’s the point.

We can’t write the backstory and then design an adventure to fit the backstory. And we can’t design an adventure and then figure out the backstory. The Arkham approach requires us to build BOTH the story and the adventure simultaneously. And to let each inform the other. Here’s a really simple example of why.

Approximately once a level, we need to have at least one major victory or significant event. The party has to find a significant treasure, defeat a specific enemy, or change the environment in some way. That’s part of the pacing thing that we’ve been talking about. In addition, there’s going to be other things dictated by the pace of the adventure. Like, we need a boss for the dungeon. Because bosses are cool. And they are a fun climax. And we need ways to lock off areas of the dungeon until the right moment. And then we need ways to make the party WANT to go down those hallways. Or NEED to.

The point is, there’s feedback between the story and the game. So we’re constantly going to be tweaking. We’re going to be shifting stuff around. We’re going to be changing numbers or adding details because either the story needs a beat that the numbers aren’t aligning with or the numbers need to do something that the story isn’t providing a good reason for.

BUT, we also can’t just build everything as we go. We can’t just make up s$&% randomly. For the same reason that we aren’t just mapping out a big ole site and throwing encounters into it, we also can’t just come up with a neat backstory and drop the details in our game. We made a spreadsheet that represents our ideal goal for the mechanical progression of the game. What we need is a similar spreadsheet that represents our ideal goal for the story of the game. Except that’s not something you put on a spreadsheet. That’s different.

The Big Ole Pile of Story

One of the things I did when I first started planning this whole project was to sit down and start doodling. Because, in the end, this is the story of a location. And that means that the design of the location is kind of important. And while I was doodling, I came up with bunches of evocative images and ideas and bits and pieces. I wasn’t writing a story. I wasn’t designing a site. I was just vomiting forth whatever seemed neat into a big pile. And that’s kind of how you do it. With mechanical planning, you do spreadsheets. With creative planning, you do idea piles and doodles and random half-formed sensory things. Whatever strikes your fancy.

And that’s what we’re going to end with. I’m going to share the big ole list of s$&% that would probably neat to have in this adventure. Not all of it is going to end up in the adventure. I can tell you that my original doodle thing was WAAAAAAAYYYYYYYY too big. And some ideas just aren’t going to end up in the final project. But it’s important to have them there so that, as I’m planning to a budget, I’m also planning to a tone and to themes.

So, first of all, let’s talk about the evocative images I was enamored with. These are the general themes.

Setting wise, I wanted a varied location. And I wanted it to be constrained. I like working underground. And I like natural caves. But I also like shrines and big halls and all that dwarven crap. But, honestly, I didn’t want to do dwarves. All ruins are dwarvish. What I really wanted to do was to juxtapose an earthy, underground complex with an unusual origin.

At the same time, because of the games I was playing, there were some specific things I wanted to play with. I wanted to play with some specific things. For example, I liked how Metroid Prime had these transitions between enclosed areas and outsidish areas. The ruins you first explore in Metroid Prime have all these places where the roof is open so plants can grow. It’s like a mixture of caves and gardens. But, at the same time, they are very dried out because of the disaster that struck. And all of those images resonated with me.

I wanted a sort of sanctuary garden type deal that had lots of gardens and grottoes and natural caves and ponds and canals. Like a half-underground botanical garden. Earth and water elements. But I also really liked the idea of it being dehydrated. The area is dead. Choked with sand. The husks of dead trees. A garden that hasn’t been watered in centuries.

And that played into a scene from Dark Souls that was very powerful for me. There’s a flooded, ruined city. And, eventually, to access the part of it, you have to open a floodgate and drain the water. And when you do, something horrible happens. As the water drains, you discover that the streets of this ruined city are filled with muddy corpses. Piles and piles and piles of them. Hidden under the water was just this mass grave for the people who couldn’t escape the city when it flooded. It was horrible. It also reminded me of a sad little thing in The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. When you drain a pond at one point in that game, you leave this little flopping fish high and dry. And that got me thinking about the idea of what a strange environment would be left if you had to explore something that had been completely underwater. Say, you had to explore underwater caves AFTER you drained the water from them. All the silt and mud and the dead aquatic creatures and the strange underwater plants hanging off everything.

And those two ideas combined to create the biggest gimmick I knew I wanted in the game. There was a dessicated section of the dungeon. There was a flooded section of the dungeon. And at some point, you would restore the water flow to the dessicated section, draining the flooded section. That created at least three environments.

There are also other cave gimmicks that are always fun to play with. Caves that are cursed with ghosts. Lightless and evil. Caves filled with sharp crystals that create a beautiful but deadly highly magical environment. Lava caves. After all, I love working with demons and elementals.

And I realized that I was working with a very elemental dungeon. Water, earth, and fire, at the very least. And nature or life instead of wind. And the idea that the elements are out of whack. Or at odds with each.

Once you start thinking along those lines, that leads to other places. First of all, spirituality and naturalism. Second of all, four part things. Four elements, four seasons, four aspects. There’s a nice double symmetry to the whole naturalism thing.

And that lead to other things. Grand waterfalls. In fact, I liked the idea of a waterfall plunging down deep into a fiery volcanic cave. A place filled with steam and glassy minerals. That would be the deepest part of the dungeon. Where water meets fire. Which leads to the idea that demons and elementals are stuck down there.

And that goes back to the idea of the flooded section. Maybe the flooding was deliberate. Maybe sections of the dungeon were flooded, dehydrating other sections, in the last desperate attempt to contain something.

The other thing I liked, the other thing that resonated with me was the Poison Ivy thing I mentioned briefly above. In Arkham Asylum, Poison Ivy becomes mutated by a powerful chemical and she becomes super powerful. At that point, the environment is overgrown with giant plants that are obstacles to your progress. They withdraw once you defeat Ivy. The reason that stuck with me is because I have this miniature that is basically a giant venus fly trap monster. A sort of Spore Spawn for D&D. And I’ve always wanted to have a neat fight based around it. The fight would be more than just a straightforward combat because the creature and its lair would be one and the same. The head of the creature couldn’t move, but all the plants around it were under its control. Wouldn’t THAT be neat?

And that lead to other ideas. I like the idea of stuff being overgrown. And I always equate plants with poison. So, I liked the idea of toxic plants that had overrun this natural shrine. That was something else that would make a good event. Defeat the source of the toxic plants, it’s runners and shoots die, opening new areas, withdrawing poison clouds, and opening new areas to explore.

But if I’m going to have an evil plant centerpiece, I’d also need a good plant centerpiece. After all, if this is a naturalist shrine, it’d be built around something big and worthy of worship. A giant tree, maybe.

And then, I knew I wanted Space Pirates. I don’t mean, literally, that I wanted Zebesians with plasma guns in my dungeon. I liked the idea of a faction that lived in part of the dungeon and had a hierarchy that could serve as ongoing rivals. Good antagonists for the early parts of the game that are gradually revealed not to be the real threat. I wasn’t sure what would work, yet. But I want Space Pirates in the environment.

At some point during all of this pontification, which, by the way, didn’t happen as a rigorous process the way I’m spelling it out. Instead, it was the sort of thing that filled my thoughts idly while I was looking at the mechanical bits and pieces. Or while I was in the shower. Or driving to work. Or leafing through Monster Manuals. Or replaying favorite games. Because that is a thing I did too. I kept replaying the games that were my biggest influences. I’m still replaying them while I work through this project. And I just kept all of this crap in my head.

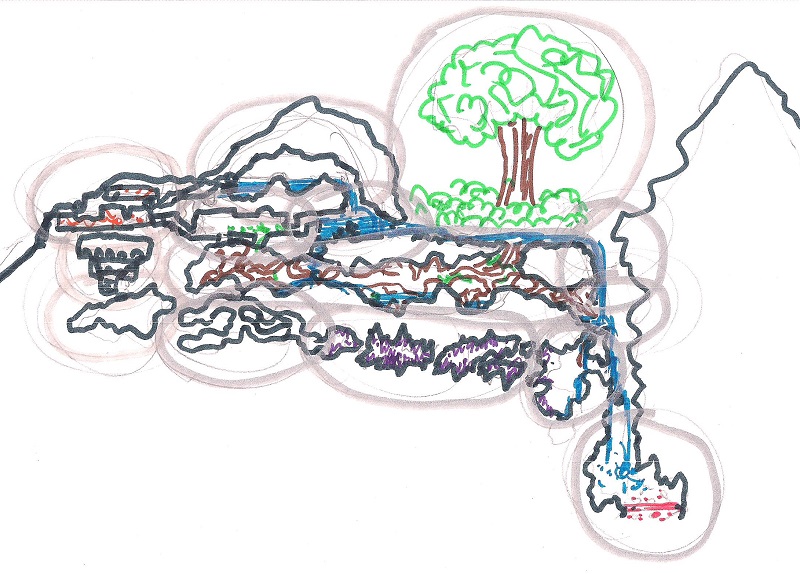

And then, it reached a critical mass. It reached a point where I grabbed a piece of paper and I started doodling. And gradually something took shape. A side-view map of the complex. I did a couple of different doodles before I liked one. And I took my markers and went over the pencil lines I liked in marker and colored bits in. And that’s what you see here. It’s just a doodle. It’s not a map. Just a bunch of setting ideas that spewed from a pencil. Basically, there is an overgrown crated filled with a miniature forest. And in the mountain around the crate is this sanctuary complex and the caves underneath it.

And THEN, I took my map and circled what seemed like distinct features or areas. And we’ll talk more about how and why I did that in a future article. But for now, just understand I was trying to separate the distinct environments. My Brinstar and my Phenadrana Drifts and my Blighttown and my Lost Woods and my Arkham Mansion. I circled them in a big, silver marker.

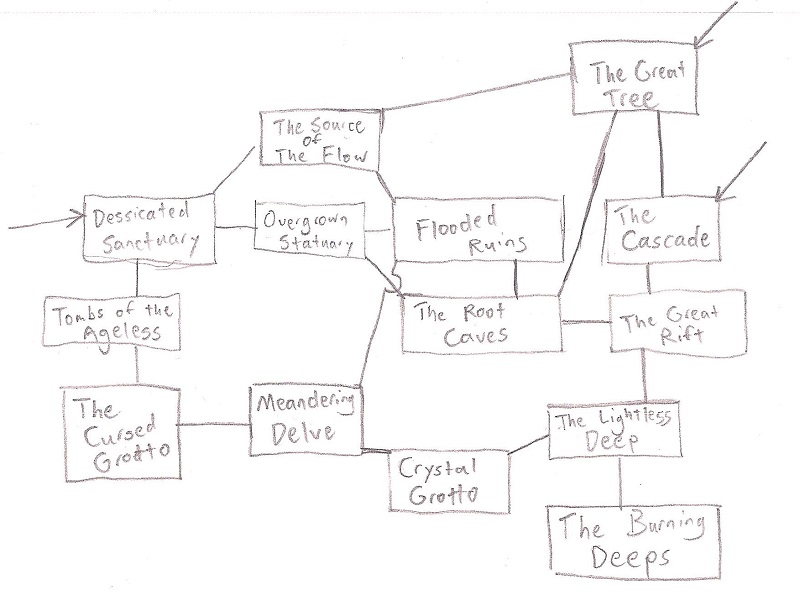

And FINALLY, as the last step in this process, I took what I had circled and turned it (loosely) into a flowchart. And I gave each area a neat, evocative name that I pulled out of my a$&. Whatever seemed neat and descriptive, it went on the paper.

And FINALLY, as the last step in this process, I took what I had circled and turned it (loosely) into a flowchart. And I gave each area a neat, evocative name that I pulled out of my a$&. Whatever seemed neat and descriptive, it went on the paper.

And THAT is ultimately the spreadsheet for the story of the dungeon. This vague idea of what the environment contains and some disjointed story elements and key events. It isn’t complete, yet. But it’s a starting point. Just like the spreadsheets are the starting point for the adventure structure and encounters.

It Was Elves

One last little note. Just to show how disjointed and serendipitous this whole process ACTUALLY is. As I sat there looking at the map, suddenly, I realized elves had built it. This is a wood elf sanctuary. Built in a very unlikely place for wood elves. Into the side of a mountain. The great tree was the center of their sanctuary. And then they started building out the caves into shrines and gardens and mediation places. A sort of monastery. But there was something bad under it. And eventually, that destroyed it. And the elves contained the bad. But they didn’t destroy it.

This megadungeon is gonna be so awesome. Those drawings and names got me super stoked.

Hey, Angry, you know all this three-act thing is a myth, right?

Unless you mean all stories have beginnings, middles and ends, which is not a very helpful observation at all. What is an act, after all?

This guy here puts it quite well:

http://birthmoviesdeath.com/2013/12/11/hulks-screenwriting-101-excerpt-the-myth-of-3-act-structure

My god that caps lock was irritating.

If you must:

http://convertcase.net/

I don’t think Film Crit Hulk’s intent is to say nothing can ever adhere to a three-act structure, but that using it as the only way to write or analyze screenplays is crippling and limiting.

Regardless, most of what he says applies to character development and action–something which the screenwriter/director has nigh-absolute control over. A DM does not. Players gonna roleplay. A DM can influence character development (e.g., by providing dilemmas, moral quandaries, or revealing backstory twists) but can’t force the player to react in a certain way. (If they do, they’re running a community theatre group, not a roleplaying game.) So the Shakespearean five-act model is hardly better for RPG campaigns either.

Honestly, I think his point is a bit like saying water is a myth because, when you really look down to it, it’s a collection of protons and neutrons and electrons. The thing is, the three-act structure is a very broad analytical tool for understanding the pacing of a story. And there’s more to it than just beginning, middle, and end. There are specific things that go in specific places. And the transitions between acts do particular things.

BUT there is a lot of complexity that underlies the three-act structure too. There’s more to a story than just act one, act two, and act three. And saying “act two was f$&%ed up” is useless critique because it’s such a broad thing to say. Good criticism has to dig deeper. But sometimes, the lack of a good act structure is enough to screw with people’s sense of whether it’s a good story. I’ve talked A LOT about how the human brain expects certain bits of structure to happen.

Moreover, the three act structure is not the ONLY structure. But it has outcompeted a lot of other structures for a variety of reasons. The fact is, the three act structure is a pattern people noticed in the stories that resonate with the most people. That’s all it is.

The fact that water is made of individual molecules which are themselves made of atoms which are themselves composed of quarks and leptons doesn’t mean water is a myth. It just means you have to be aware of the different scales. If we’re talking about why water has its chemical properties, it’s silly to talk about water as water. We have to talk about molecules and atoms. But that doesn’t invalidate talking about water when that’s the appropriate level to talk about it.

Finally, I LOVE when someone finds one of these articles and then takes it as gospel. “You know the three act structure is a MYTH, right?” like that’s some sort of established fact. No. No it is not. This random dude on the Internet says it is a myth. That’s not gospel kiddo.

Well, I think his point is pretty convincing because he actually has a working definition of what an act is, while the “three-act structure” theory just sort of waves its hands about it.

Taking your example of The Fellowship of the Ring, I would argue his definition makes for a better description of the overall pace of the story than “three-act structure” does. If you are married to 3 acts, the middle part sort of comprises almost everything, and the transition between second and third is kind of blurred as you admitted yourself.

However, using Hulk’s definition, everything gets a bit clearer. I would put it more or less like this (based mostly on the movie, which I saw over a decade ago):

1st transition: hobbits leave the Shire

2nd: they dont find Gandalf and decide to trust Strider

3nd: hobbits arrive in Rivendell

4rd: fellowship is formed and leaves Rivendell

5th: they decide to enter Moria

6th: they leave Moria and Gandalf dies

7th: Boromir tries to take the ring, Frodo and Sam flee, Fellowship is broken

I take it that your point about water is that a 3-act structure is a good enough aproximation for our purposes. After all, you could “zoom in” so every scene is an act or more. It is a good point, but I feel this may be too much aggregation to really help with pacing? After all, if basically the whole book is second act, how do you pace that? It doesn’t feel very helpful.

About the whole “myth” thing, I admit I was trying to be provocative, sorry about that. This is just something some guy said. So is 3-act structure.

Anyway, I’m glad we’re having this conversation. I love your blog, I think you’re really awesome and wish you all the best. =)

*Please forgive any errors, English is not my first language.

I had a case of the burning deeps once. There’s an ointment for that.

I look forward to these articles. When I see a new megadungeon article, literally everything stops and I read. I pulled over while driving to read this one. Just following along eith these first articles my design process has changed entirely. Thanks Angry for all the good work.

I just want to say, as a person whose enamoured by maps, and has a burgeoning collection myself, I love yours. Particularly the colour (I usually do pencil, then print them in high contrast black-and-white). Also, I’m glad you mentioned Acts! I’ve been running a long campaign that’s taking place over FIVE acts, and was wondering how weird that was. Each “act” consists of its own internal, (interlocking) beginning, climax, and endgame though, as it just seems that stories naturally do that. This mega dungeon is shaping up to be super awsome! Your hard work is very appreciated!

This is my new favorite series of yours! The finished product looks like it will make me pick up the latest DnD again, whenever you finish. (And take your time, it’s fun following along)

So I know that “Every Adventure is a Dungeon”, especially in terms of structure, but in terms of your specific megadungeon, do you think it will have a different balance of Exploration/Interaction/Combat than a “standard” adventure.

I know you’ll have space pirates, but barring some sort of civilization or whatever, I feel there will be less NPCs when compared to an adventure that involves a city.

Can you provide any clarification on this?

Yes. A dungeon is, by its nature, action-focused and interaction light. That’s why people buy dungeon adventures. I don’t plan to subvert that.

Even if you weren’t going to be publishing this, I’d be stealing the heck out of these ideas. I love elemental-themed dungeons, and my players do too.

Of course, this is what I’m better at (or just like more), the fluffy stuff. Your articles on the crunch of it all have been extremely helpful to me, can’t wait to see more.