Nothing is harder than starting. Think about it. As a GM, how long do you sit and stammer and flip papers and bulls$&% at the start of every session before you manage to set the first scene and get the game started? Lately, I’ve been having a hell of a time getting things started. Once I get rolling, I’m fine. But getting started sucks. That’s why the last article about campaign building began with “I’m not in the mood for this s$&% today.”

The problem with this particular series – the one about planning and building a campaign – is that the actual process I’m trying to describe is a f$&%ing mess. Once you get past talking to your players and having a Session Zero and gathering a whole bunch of information and your head is a swirling miasma of scintillating thoughts and turgid ideas, you have to face down the most powerful, most insurmountable obstacle in the entirety of GM-ing-dom. You have to face a blank piece of paper.

As an aside: one of the reasons I hate computers is because physical, tangible media lends itself to nice, clear analogies. It’s far more aesthetically pleasing to say “blank piece of paper” than it is to say “a Word Document with no bits and bytes in it yet” or whatever.

As another aside: holy f$&%, this opening is working out better than I thought.

The point is, once you get past all the preplanning and brainstorming and Session Zero-ing, you’re left with the task of actually coming up with a campaign. And I don’t just mean deciding how the plot threads are going to fit together and what setting you’re going to play in. I mean “what is the game actually about?” Believe it or not, saying the campaign is a “plate of spaghetti campaign” in which the characters are unified by one of the plot threads which involves saving the world while the other plot threads are character-driven side-endeavors that will follow from the character’s backstory is NOT actually planning a campaign. It’s just laying down the foundation. There’s a long way to go to get from what I said to Mass Effect.

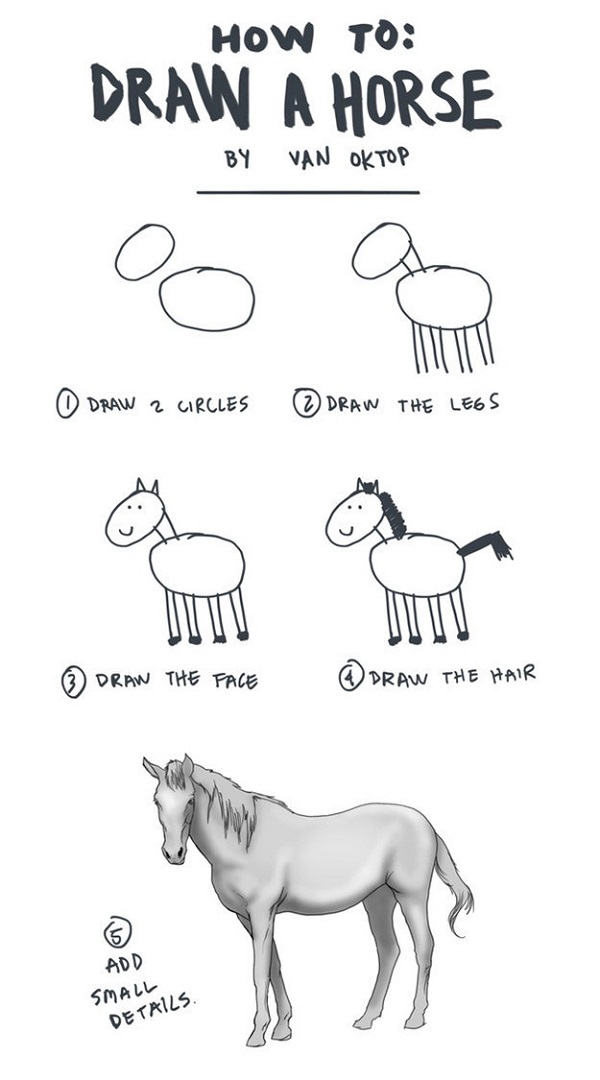

So far, I’ve talked about all the deep, foundational, structural concerns. Here’s HOW to pick a structure for your game. Here’s HOW to plan a way to keep the players together. Here’s HOW to go from a single idea to a plot-thread. And so on. But to say that I’ve taught you how to build a campaign is like saying this teaches you how to draw a horse from Van Oktop’s tumblr:1

Here’s the real problem though. At this point, you really ARE facing a blank sheet of paper and you can really fill that blank sheet of paper with ANYTHING. The possibilities are as endless as your imagination. Or, rather, my imagination. I have a really super amazing imagination. Yours probably sucks. But that’s okay. Use what you got.

Here’s the real problem though. At this point, you really ARE facing a blank sheet of paper and you can really fill that blank sheet of paper with ANYTHING. The possibilities are as endless as your imagination. Or, rather, my imagination. I have a really super amazing imagination. Yours probably sucks. But that’s okay. Use what you got.

And I can’t teach you how to come up with an idea. I can tell you what things your idea should cover and what concerns your idea should address and all of that crap. But I can’t actually say “here’s how you come up with a good storyline or structure or whatever.” And I’m not going to try. Sorry. What I CAN do, however, is to talk about some higher-level concept stuff and hope that helps you drill down to your ideas. We can discuss things like “save the world” campaigns in general terms. Or “exploration” campaigns. Or “adventure of the week” campaigns. We can talk about how specific motivations – specific glues – change the feel of a particular game. We can talk about what campaign elements will help bring about this or that engagement. And that’s just what I’m going to do.

The problem is, there really isn’t any sort of good order to present these things in. They are basically just essays on different aspects of campaign design and how different ideas and game elements play into the campaign you’re trying to design. And what I hope they will do is put some margins and guidelines on your piece of paper. Because there is nothing harder to fill than a completely empty sheet of paper.

In that spirit, today, I’m talking about scope and scale, and safe havens. Doesn’t that sound like a nice title?

Scope and Scale and Safe Havens

Let me start by admitting this: scope and scale are totally overused words. And totally misused words. And frankly, I’m not using them entirely right. I’m only using them because “scope, scale, and safe havens” is a nice, alliterative title that sort of gets where I want to be. This isn’t going to be one of those articles where I nitpick over definitions. I just need some f$&%ing way to get started.

That said, I am SORT OF using them VAGUELY correctly. And that means we do need to discuss them a little bit. Scale refers to the size of something. Scope refers to how many different things… of… something… there are. You know what? Let’s try an example.

Suppose my campaign takes place in a huge desert. There’s a single city-state on the edge of the desert, a pyramid for the players to plunder, and a whole bunch of sandy wastelands for them to wander around lost in. The city, the pyramid, and the desert are all huge. They will take months and months of game time to explore and plunder and overall just finish playing with. That’s a large scale campaign. It’s big. It takes lots of time. Right?

Now, suppose my campaign is still set in a huge desert. But the desert is more like the world of Athas. There’s rocky badlands, sandy dunes, seas of silt, oases, fertile river valleys, deltas, rocky shores, and so on. And across this desert, there are numerous civilizations. There are dozens of city-states, enclaves and encampments of different races, and even a small kingdom or two. And there’s pyramids and ruins and caves and dungeons of every variety. Now, everything in the game is pretty small. The pyramid takes just one session to explore. The players only spend one or two sessions in each town. And so on. That campaign has a broad scope. There’s a lot of different types of things happening.

In short, scale is about size and scope is about variety. Sort of. That’s a good enough definition for our purposes. Except not really. Because, when it comes to RPGs, “campaign” is actually a measure of scale. We talked about that a long, long time ago. Basically, a campaign is the “biggest unit of game.” Right? Campaigns are bigger than adventure paths. Those are bigger than adventures. And those are bigger than encounters. Sure, some campaigns last for three months and some last for a year and some last for ridiculous numbers of years, but that isn’t really a big difference. Not in practical terms. As for scope, there are lots of ways to build variety into the game. So many ways that it’s really silly to say that scope is simply a matter of “how many different types of environments are there to explore.”

So scale and scope are pointless to discuss.

Glad we got that out of the way.

But we can talk about the vague idea of “the scope and scale of the campaign” as a single concept that describes, roughly speaking, how much ground are the PCs going to cover in this campaign. Geographically, how much ground does the campaign cover? How many miles will the PCs have walked, ridden, sailed, swam, flown, and teleported by the time it’s all over? How many different peoples and places will they have seen over how many different terrain types?

The question of the “scope and scale” of the campaign plays directly into world-building, obviously. The more ground the PCs will cover, the more world you will have to build BY THE END OF THE CAMPAIGN. I stressed that part because it’s important to remind some GMs that you don’t have to build an entire goddamned world even if your campaign is eventually going to bring the PCs across every square f$&%ing inch of it. And I remind them of that just so I don’t need to read some comment reminding me that “start small and build” is the best way to approach world building. It isn’t, by the way. It’s a good option. But it’s not the only option. And it’s not always the best option. It depends on the campaign that you’re going to run in the world. But we’re not ready to talk about world building yet.

Beyond that, though, there is a very important to consider the “scope and scale” of the campaign. That’s because it plays into several important bits of the narrative structure of the game. And the most important of those bits are the bits I call “safe havens and home bases.” And, in the end, those two ideas – “scope and scale” and “safe havens and home bases” – lend themselves to three basic narrative structures we can discuss. Three basic structures you can hang a campaign design off of.

Now, I should point out that the structures I’m going to discuss today are neither entirely inclusive or entirely exclusive. What does THAT mean? Simply, it means you can’t break down ALL campaigns into one of these three categories. I mean, you SORT OF can, but it isn’t totally useful. Campaigns are like food. You can define food as “sweet or savory” or you can define it as “healthy or comfort” or you can define food by food group and nutrient content or by the allergens it contains or by the ethnicity or whatever. The classifications you use depend on what’s driving the decision in the first place. If you’re satisfying a food craving, knowing whether you want something sweet or savory is important. But if you’re a diabetic and you’re planning a meal, food groups and nutrient content are the way to go. And if you’re going out to dinner with friends, ethnicity is probably the main classification.

So this “scope and scale and safe haven” bulls$&% describes one specific sort of spectrum you can use to describe a campaign if the things it describes – which we’ll get to – are important considerations in your campaign. If they aren’t, you’ll need another way to think about things.

The Bigger the Scope and Scale…

A campaign that is large in scope and scale is one that covers a lot of ground. It’s one in which the PCs travel a lot. That doesn’t mean the campaign has to cover an entire world, mind you. The PCs can spend years and years exploring one corner of one region of one continent depending on how densely packed that region is. Geographical size does not make a game large in scope and scale. A campaign that is large in scope and scale is one in which the players are never in the same place for very long and only occasionally return to a place they’ve previously explored. And when they do backtrack, it’s usually for a short time and for a specific reason.

The Lord of the Rings, Star Trek: The Next Generation, almost every Final Fantasy game and every Dragon Quest game, those are all works I’d describe as large in scope and scale. Got it?

Games that are large in scope and scale are generally sold on the size of the story or the amount of exploration involved. Lord of the Rings is an EPIC adventure. Star Trek was about EXPLORATION. If your players want an epic feel or they want to explore the world, or if you love world-building and want to do a lot of it, these are the games for you.

Narratively, such campaigns can take any shape. But there are similarities in the structures regardless of the overall shape. Adventures tend to be isolated and disconnected. The players come to a new place, explore it for a bit, have an adventure or two, and then move on. Ongoing plot threads generally provide the impetus for the travel. For example, the party might be trying to reach a particular location in a far distant corner of the world and they have lots of adventures along the way. They might be hunting or chasing someone. They might be collecting the various bits and pieces of a magical artifact from eight differently-themed temples. Alternatively, they might simply be going wherever the wild winds of fortune take them. They might be explorers or pirates or fugitives, constantly on the move, and having an adventure in every port.

It’s Not the Scope and Scale of Your Campaign…

Campaigns that are small in scope and scale aren’t really the opposite of campaigns that are large in scope and scale. They might seem like they are. But they are actually more “different” than “opposite.” The players in such a campaign generally keep returning to the same locations or else they never leave the location in the first place. They never have to concern themselves with travel or survival for long periods of time. And they rarely have adventures “on the road.” The game isn’t really about getting anywhere.

This is where the “different but not opposite” thing is really important. A campaign set in a single city can be large in scope and scale or small in scope and scale. Really. I s$&% you not. And I’m not trying to confuse you here. If every adventure takes the players to a new neighborhood or a new location and they never go to the same place twice, the campaign is large in scope and scale. And it will feel that way. Sort of. Honestly, that campaign would feel weird. But it’s just an example.

The thing that really makes a small in scope and scale campaign is the fact that the players have a growing sense of familiarity with the world around them. There are recurring characters and factions and locations that the players get to know and interact with regularly.

Much of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, all of the Discworld books set in Ankh-Morpork, the first Diablo, and the Grand Theft Auto games are small in scope and scale. They involve the same locations and characters over and over.

Now, every game needs variety. And every game needs to expand over time. Campaigns that are small in scope and scale are no different. But, even as they are adding the new features, the old stuff never goes away. The players never move beyond the features that already exist. And if things do change or disappear, it’s because the setting is evolving, not because the players have moved on. In fact, that evolution is a major feature of campaigns that are small in scope and scale. Such games offer the players a chance to immerse themselves in a living, breathing, evolving world. That’s the selling point. They become familiar with their surroundings. They get to interact with the same things over and over. To learn more about them. And they get to watch everything grow and change.

See what I mean? Different, but not opposite. Players who want to immerse themselves in a world and experience its evolution aren’t the OPPOSITE of players who want to explore a world. They are just different.

Narratively, campaigns that are small in scope and scale also share a common structure regardless of their overall shape. And that shape is generally the hub-and-spoke shape. Usually, in such a campaign, there’s a central location to which the players frequently return. A home base. But – and this is important – that central location isn’t JUST a place to rest and recover and level up. Most adventures involve at least a few scenes in that central location. Or at least in familiar places within that central location. Often – but not always – adventure hooks are found in familiar places. And during many of their adventures, the players have the chance to interact with recurring characters in familiar locations. That’s the difference. They aren’t just sleeping in their dormitory between adventures; the players are spending actual game time in familiar places with familiar characters. In a plate of meatballs style campaigns, the players tend to spend some time in the central locale gathering information and gearing up for each adventure, then they strike out for the adventure, and they return home when it’s all done. Many adventures might even take place entirely within that locale. Plot threads in the campaign generally involve recurring characters and factions and weave in and out of the central location. Or else they revolve around the location itself. The players might be adventurers based in a town or village who take on jobs for the locals in and around the city or town. A plot thread might involve a looming threat to the location or the people who call it home, like a pending orc invasion or the local Hellmouth getting uppity. Or the plot thread might involve several guilds and factions vying for power. All of your political intrigue campaigns belong firmly here in the small in scope and scale category.

Of course, the size of the central location can vary. It might be a single fortress or guild hall or monastery. It might be a village, a town, or a city. It might even be a small county or province; for example, it might be a market town, the surrounding farms and villages, and the lord’s keep or manor nearby. The size doesn’t matter. What matters is familiarity.

And THAT brings us to an important, related concept.

Safe Havens and Home Bases

In a campaign that is small in scope and scale, the game tends to center on a single location the players return to frequently, right? That location serves as the rock around which the campaign is centered. Adventures start there and end there and often take place there, either in whole or in part. That location – whatever it is – becomes familiar over time. More importantly, it becomes safe. The players know they can retreat there whenever they need to. And they can restock and regroup there. Basically, it becomes a safe haven and a home base.

Now, safe is a relative term. Often, the entire location is not completely safe. If it were completely safe, there would never be any adventures or encounters inside of it. And the location may also be subject to a distant, looming threat that provides a plot thread for the campaign. But any danger is of the temporary and highly localized variety or else serves as a plot point in the distant future. Or else, it might serve as a drastic upheaval that completely changes the campaign. In fact, a disaster in a home base can change a campaign from small scope and scale to large and scale. That’s an example of an advanced sort of campaign structure that involves capping off a major adventure path or plot arc with an event that completely changes the entire campaign going forward. Such changes can be very cool when they don’t feel like a huge screw job and make the players hate the campaign. They can also help stave off GM burnout.

But I digress.

Every campaign that is small in scope and scale has, at its heart, a safe haven or home base. Which is why people sometimes call such campaigns “home base campaigns.” At least, I do. I think other people have used the term. I don’t know. Who gives a f$&%. We’re calling them that now.

The home base at the heart of the campaign is what provides the unique selling point for a campaign that’s small in scope and scale. Remember, those campaigns promise the players and GMs a chance to get immersed in a setting that will grow familiar and comfortable over time. They get to build relationships with the setting and its inhabitants over time and to see the consequences of their actions in a very personal way. They get to see how the campaign evolves over the course of their adventures and, most importantly, as a result of their successes and failures. And knowing that – and knowing that large and small scope and scale campaigns aren’t opposites – we can do a really neat trick.

One Size Fits Some

As I mentioned above, large in scope… f$&%, that is getting tedious as hell to type out and I have no idea how to use macros. Okay, I’m just calling them large and small campaigns, okay? For the purposes of this last section of this article, when you see large or small, just add the words “in scope and scale” okay? I wish I’d thought of that, like, 3,000 words ago. But whatever.

Large campaigns have an epic feel and emphasize exploration. They also emphasize character growth and important quests. The distance the players travel becomes a symbolic representation of how far the characters have come and how close they are getting to their goals. And they are great for world-building GMs who have a lot of big ideas and want to cram them all into the same game.

Small campaigns are homey and comfortable. The emphasize relationships between the players and the game world. They are immersive. They draw the players in. And they tend to strongly emphasize the consequences of the players’ choices. Players feel like a part of the world. And, depending on how their actions shape the world, they might even start to feel like they own the world. Or, at least, they are responsible for keeping it safe. In short, they care.

Now, let’s say you want to find a middle ground. Maybe your players are mixed between the two sensibilities. Or you want to do the big, epic thing and your players want to be happy homebodies. Or you want a big, epic campaign about exploration but you don’t want to constantly build new venues week after week after f$&%ing week. Well, there’s a neat trick you can do. You can insert a safe haven or home base into a large campaign. You just have to figure out how.

After all, even though large and small campaigns are NOT opposites, there is a little bit of an oil-and-water thing going on, right? How can you have the players travel to new places every week and never go back to where they came from and also have them return to the same place week after week and see it grow and evolve as they get attached? Well, you can. You just have to be creative. And I’m going to give you two ways to do it. These aren’t the only ways. But they are good ways. And, more importantly, they provide a great example of how to dig down into the heart of two different campaign ideas to smash their guts together and get the best of both worlds.

First, there’s the beatbox campaign. You know: “hub-and-spokes-and- hub-and-spokes-and-hub…” In a beatbox campaign, the players tend to travel from one home base to the next. At each, they settle down for a while, do a bunch of adventures, get attached to the location, get to know the people, get immersed, and then they move on to the next home base and do it all again. This is very much how World of Warcraft is structured. The players get to experience big, new places every so often, but they also get to get immersed and attached to those places. For plot- and character- campaigns, each location generally has a plot arc running through it that links all or most of the adventures. Once that plot is resolved, the heroes learn about some other location that has a new plot arc or else the resolved plot thread leaves a loose end that draws the heroes to the next location. For more quest driven campaigns and “adventure of the week” style games, the transition from one location to the next is generally driven by the players’ power levels. In fact, the beatbox campaign is an excellent way to create a campaign with the feeling of an open-world, exploration-based sandbox but still maintain a good challenge and level progression. In each location, the heroes grow from small fish to big fish until they finally head off to look for a new, bigger pond.

Second, there’s the turtle campaign. In a turtle campaign, the players have some sort of traveling home base or safe haven they bring with them wherever they go, usually with a cast of recurring characters along for the ride. The simplest example is a seafaring campaign wherein the players have their own ship and crew. They get to build relationships with the crew and learn the crew’s backstory and see how their actions and adventures affect the ship and crew. But they also get to travel around the world and see new locations. Of course, ships – and airships – are only the start of it. You could get the same effect if the PCs were members of a group of wandering exiles looking for a new homeland or returning to their homeland or something like that. The exiles set up camp wherever they go – they aren’t, for some reason, welcome in the towns and cities they visit – and that camp and its members become the safe haven and recurring characters and all of that crap. But you don’t even have to stop there. You can do really fantastic stuff with magic. The heroes might be agents serving the king of a flying castle that travels the world. Or they might be the protectors of a village that’s built on the back of a massive sea turtle. They have no way of controlling where the sea turtle goes, but they have to protect the village from whatever’s there. And keep the village supplied.

So there you go. There’s two different campaign structures at opposite-but-not-really-opposite ends of one of an infinite number of non-exhaustive and non-exclusive spectrums that you might use to define certain aspects of the campaign your trying to fill your blank page with and two creative ways to mash them into a crazy middle ground that gets you a little bit of the flavor of each. And that, really, is what lies at the heart of campaign building. Figuring out what the hell you want to run, what they hell your players want to play, and then finding some crazy-a$& way to fill a blank sheet of paper in a way that somehow does some of that. Draw some circles, add some lines, and then fill in minor details until you’ve got two great years of gaming.

Good f$&%ing luck.

1: Yeah, that’s right. I actually hunted down the originator of that cartoon. The one that has been reposted on countless meme sites like Buzzfeed and 9Gag without any sort of link or credit for five f$%&ing years. Click on the image. It will take you directly to the image in his tumblr archive. Click here to return to where you were reading.

I suddenly have an almost overpowering urge to run a campaign out of a hub inspired by Howl’s Moving Caste…

Either way, great article. It’s funny to suddenly become aware of certain practices I’d been accidentally employing in campaign building. It seems I’ve mostly been running small games that turn into large games after a defining moment in the campaign. It’s simply interesting to realize.

This will definitely make it easier to plan the flow of a campaign, so thanks.

Well, after a 28 year haitus from D&D, I am running a game for my son and his friends ( I have been planning this for years, and I have been reading your site in the interim so that I’m prepared).

Anywho- I created my world based on real geopolitical, historic type s$!^…

” The people once controlled the world, but then the barbarians arrived to the West… After the invasion, the people retreated beyond Big A$$ River (which divides the continent); The people had to build a 15′ wall (‘Long A$$ Wall’) to keep the monsters out. But now the population has recovered, and the Fuedal Lords are recruiting skirmish parties to retake the land, set up strongholds, and start settlements. Your party will work 2 weeks on (designated assignments) and 2 weeks off (pick your adventure); ”

Well, like I said, it’s been 28 years since I last played, so wish me luck…

A campaign I played in years ago would have benefited greatly from reading this article.

The party began sailing on a ship, heading to a recently discovered land. The DM told us that this new continent was incredibly dangerous, and to his credit, he played that up very well, with undead-infested jungles, constant kobold raids, and ravenous plant life.

We spent our first few levels having adventures around the port town we arrived in, getting to know the NPCs there, until one day, the whole town got burned to the ground. We escorted the few NPCs we could save through the undead-infested jungle, towards the closest city, and barely made it there alive.

Us players had spent the sessions we’d spent in the jungle discussing what we would do once we got there, and we all eventually came to the consensus that we would buy an inn, staff it with the NPCs we’d brought, and use it as a base to gather information and to go on adventures out in the jungles.

We thought we were being smart, making sure we’d always have a safe place to return to. Our DM, however, never picked up on the fact that we wanted to stay in the safe city, behind thirty-foot tall stone walls. He seemed to think we were raring to head back out into the wilderness and tried for weeks to prod us into leaving the city.

The campaign eventually fell apart, but none of us really felt any desire to get back into it. Namely, because in one of the last sessions, the DM had placed a soft Geass on our party, which said that we would have to go to another city and deliver something at *some point* in the future, or else suffer very painful deaths.

I think that, if we’d seen the issue arising *before* he decided to Geass us, we could have maybe saved that campaign, but the DM’s desire for a large campaign, just didn’t mesh well with the setting he’d made.

Real question, I’m not just being flippant here – is the “beatbox” thing supposed to be a reference to something? I don’t understand what “hub-and-spokes” has to do with beatboxing…

I think it’s supposed to be the sound it makes when you say it.

I know “boots-and-cats-and-boots-and-cats” sounds like beatboxing, but I just don’t really hear it with “hub-and-spokes”.

Maybe Angry beatboxing sounds different?

That’s the joke. It’s in imitation of the “cats and boots and cats and boots…”

You got it. Hey, they can’t all be comedy gold, okay? At least this time I didn’t call people ignorant and lazy.

It’s common for the sounds of beat-boxing music to be phonetically summed up as the words boots-and-cats. So to emulate the sounds, you emphasize the bass on the word Boots, and emphasize the treble on Cats. So you get something like this (first result I got from googling): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nni0rTLg5B8

I think the hubs-and-spokes-and-hubs-and-spokes was a reference to this boots-and-cats joke.

I like that turtle-city nomad thing. I might use that.

I’ll have the Angry Lawyers slap together a royalty agreement.

One of the things I was thinking of doing was starting as a small campaign, but them becoming bigger as the heroes gain levels and their power basically makes their missions with higher stakes. Thoughts on a campaign changing scope with player power level?

Apparently, I’ve been using this in my campaigns quite a lot, and I’m a fan of the format. It represents a big shift in your campaign, though, as there needs to be a reason why the hub you’ve been running your small campaign out of is suddenly unavailable or inaccessible, or why the PCs would leave the hub without returning to it regularly.

One of the campaigns I ran used revolutionary upheaval as a backdrop, but I wanted it to start small. The players started out as revolutionary soldiers on their way to a small, but strategically important town. They were supposed to linger there with a militia regiment stationed in the town and the adventures the players were involved in never took them far away from town; it was a small campaign.

(While they were there, they completed several side quests I had sprinkled around town, mingled with the locals, pissed off the city’s crime boss, and recovered a valuable object pertinent to the main arc of the campaign).

Then, the opposing war faction invaded the town. The characters were unprepared for the attack (they had decided to trust a deceitful NPC) and the militia force was outnumbered and in disarray. The enemies overpowered most of the charcaters’ allies and they decided to flee, which essentially turned my small campaign into a large one, as they now had to concern themselves with larger scale goals and far flung locations.

To clarify, though, you don’t have to transition into a large scope and scale campaign to confront your players with tougher missions or threats. And I think the stakes can be as high as you like in either a small or large campaign, especially if you get creative. Essentially, you can still run challenging and high stakes encounters in a small campaign.

In my example above, the players could have chosen to hide themselves within the town (they had access to hidden underground tunnels) and found a way to take it back. The campaign would have continued to have a small scope and scale, but it would have still involved difficult tasks and encounters.

I’m actually running an hybrid seafaring campaign let’s call it a medium campaign.

The adventures happens in an homemade version of the Carabean with dozens of islands of various size. The players have a boat with crew members they care about… well they care about most of them.

They also have a home town/colony where they go back to ressuply and stuff, there are alot of recurring npc there. They must travel to different islands in search of stuffs and for diplomacy and trades with other colonies.

There is also alot of piracy going on that they try to fight with the campaign boss being a powerful pirate who commands many ships and that basically searches for the same “end game treasure/legendary item” but for evil purpose…

There is alot of “visit this place once and move on” but they also visit the hometown and some particular allies quite often.

This article helped me understand that structure and how it is important to balance the scale and scope, I feel that switching between large and small makes a prettt strong campaign that will engage different type of players. Thanks again.

I tried to make a homebase for an adventure-of-the-week style of campaign by creating a town with portals into many worlds – some available all the time, some even leading to extensions of the city on other planets. Turned a city located on some hilly rock into a metropolis getting its needed resources through those portals.

The problem I ran into was how to detailed such a city need to be to feel real? Do I need to name the quarters only (as I did on my rough map of the place) and fill in locations as needed? How do I react to sudden player turns without making it feel too generic?

In principle I feel like that every time I want to introduce a city into play. Is a rough map enough? Maybe a bullet point list of prominent taverns, shops, and other services – things adventurers are likely to seek out? What is a good midpoint up to which to create stuff to make it seem alive to players? (Also in my head, for the inevitable improvisation that’s going to happen on the fly, to give the town a certain flavor.)

I guess it depends…

one way could be to have a list of names that are generic enough to fit either a tailorshop or a tavern so whatever they want to interact with you have a list of 10-20 location names. I can recommend AEG Toolbox books 1 & 2 they are basically collections of lists sorted into categories. Invented to help writers block for GMs initially. I should take my own advice and use it more, i always take it with me for GMing but rarely use it because i feel like an unprepared dumbass if i have to pick up and thumb through a book to find a name or a mundane item.

However.. writing down a copy of a few of the lists and put them on the GM screen or into the prep material or on the backside of the city map could be an idea?

You could include abit more detail in your list… Generic name + Atmosphere/tone/decor

so one entry could be “Golden Moose – Dank Dark unorganised” so when your party asks for a particular type of shop or locale.. pick or roll on the list. Middle ground between no prep and full prep.

Pingback: Constraints And Creativity | Gnome Stew