Happy Megadungeon Monday!

It’s time to take a whirlwind tour of the dungeon.

Sometimes, it’s hard to describe the design process. So much of it is about gut feeling and intuition and game design is an alchemy. It is a part art, part science, and part mysticism. And honestly, it is a LOT less regimented than it appears. I said at the start that this was a big, advanced, massive project. A magnum opus. The culmination of everything I personally believe about game design. And this is where it is really starting to show out.

As I promised, I’m going to walk you through my thought process, day by day and section by section as I created the big ole layout of the dungeon and how I overlaid the critical path on top of it. But as I started writing all of this stuff out, I discovered a few things. First, a lot happened in my brain and it takes a lot to type it all out. Seriously, this became WAY longer than I thought it would be. Which is why it kind of has to be broken down into a couple of parts. Second, there’s a lot I can’t explain from first principles. I mean, I say things like “and here is where want to start tutorializing the structure of the adventure,” and then I explain how to do that stuff. But it’s hard for me to explain WHERE that stuff comes from. So, before I launch in, I’m very briefly going to try to explain two concepts that pretty much drive everything I explain below. It’ll take three paragraphs, tops. I promise.

Where the Hell This Stuff Comes From

First of all, there’s a very basic concept called “the beginner’s mind.” Basically, you assume that someone new to your thing, whatever it is, needs to have EVERYTHING shown to them. We basically wrote out a whole bunch of design principles. We decided how our game was meant to run. How it should be played. Right? Well, we have to assume the players don’t know any of that. But we want them to have the best possible time playing the game. So, everything we’ve decided, we need to find a way to show off. And you’ll see just how deep we’re gonna go down that rabbit hole.

Second of all, a lot of the basic ideas for building the structure and mechanics of the Megadungeon comes from playing a lot of games critically. And that means basically reverse engineering the games you play. What you have to understand is that you enjoy a game because of the way it feels. The Aesthetics of a game are the things that make a player enjoy it. But when you design a game, you can’t just put Aesthetics in. You can’t just make a game FEEL the way you. Instead, you create all the game elements (which include BOTH story elements AND game mechanics) and you try to get them to create the feeling you want. This is called the MDA approach. The game designer creates Mechanics (here meaning all the different rules and systems and story elements and characters and settings and whatever), players interact with the game Dynamically, and the result is certain game Aesthetics. Playing games critically involves figuring out how the game “feels” and then working out what things it is doing to make itself feel that way.

Once you combine those two ideas – that anything important in your game NEEDS to be explained or demonstrated and that you can only create feelings by figuring out the right mix of game elements and sticking them together – then the rest involves a lot of thinking and a lot of practice and a lot of experimentation. So, while I can show you my thought process for all of this, you’re going to have to fill in some of the blanks. You’re going to have to work out some of the “whys” and “how do I knows” for yourself. Sorry.

A Tale of Two Maps

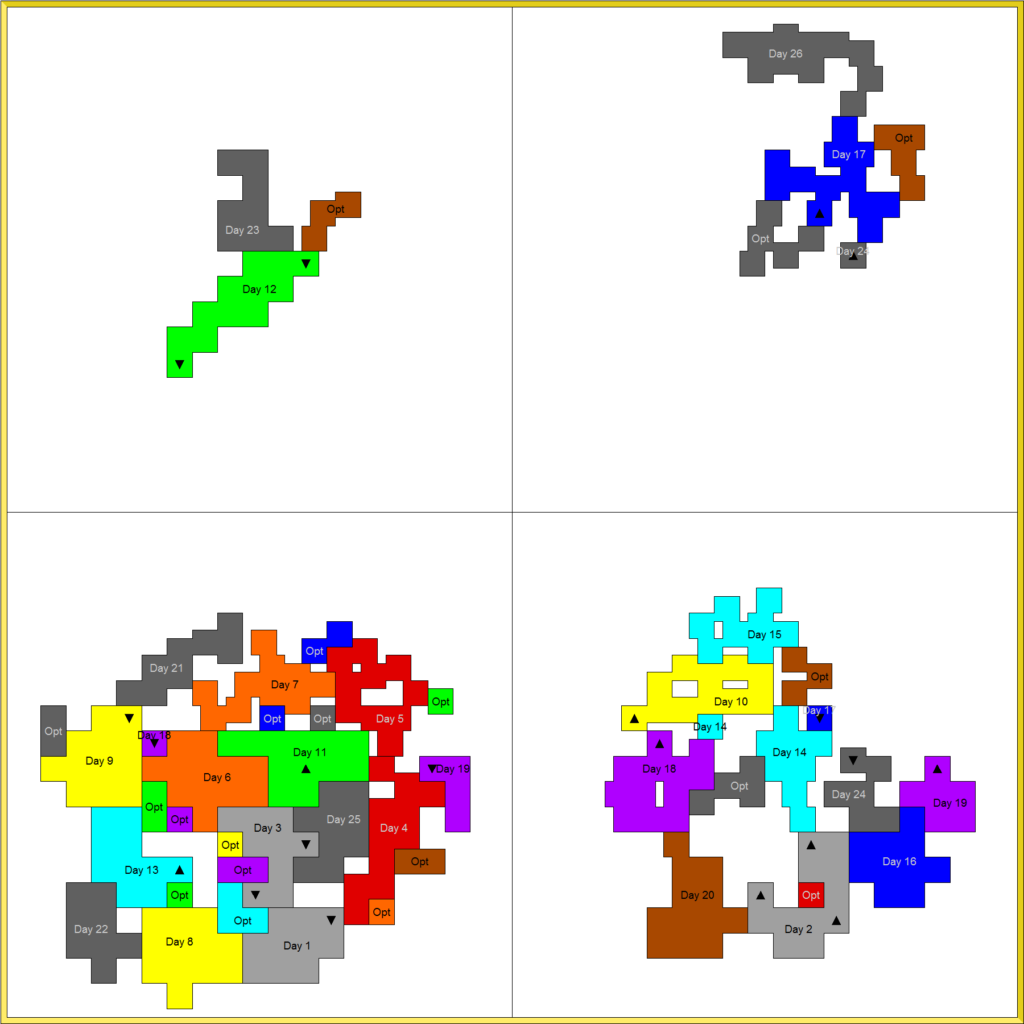

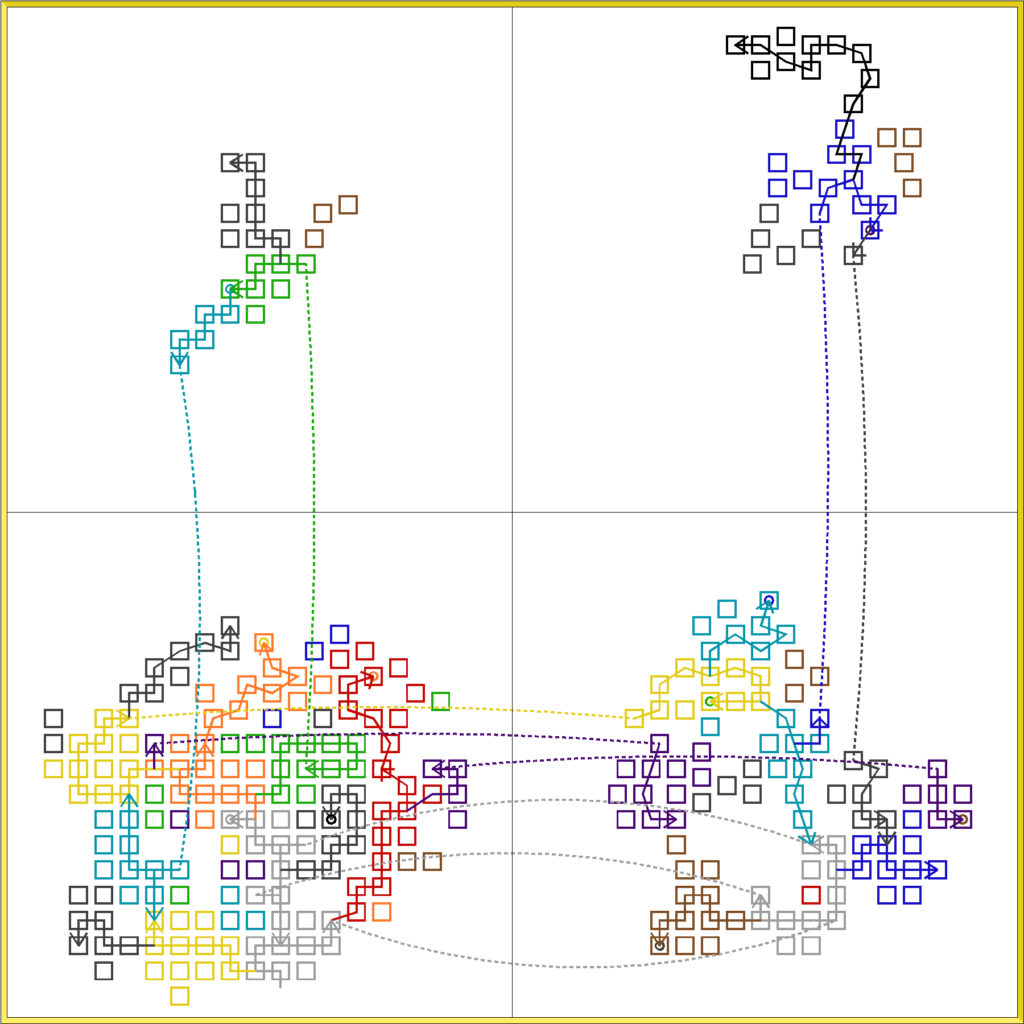

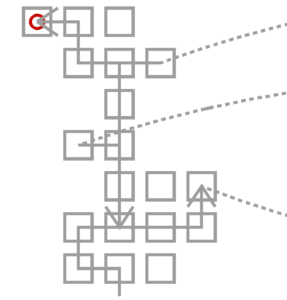

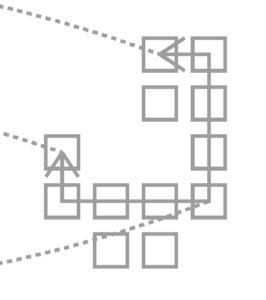

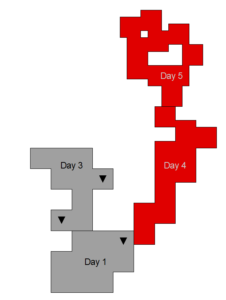

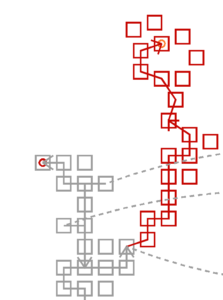

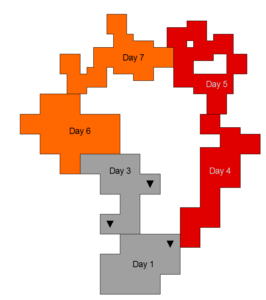

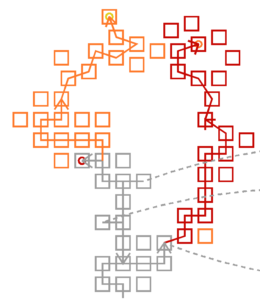

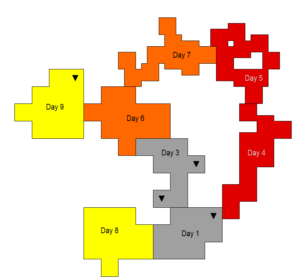

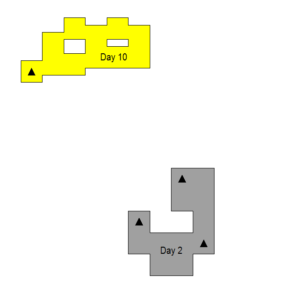

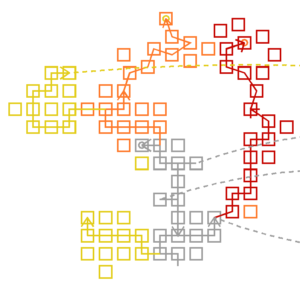

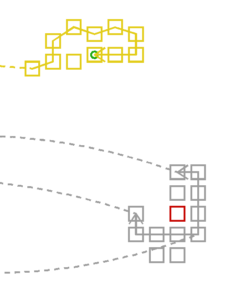

As I take you on a tour of the dungeon, I’m going to refer to two maps. The first is the blocky map that I created to lay out where the days were and how they related to each other. The second is a map of the critical path through the dungeon. And I created it very simply. I just took all the blocks I had used to create the first map and through a line through the encounter spaces to create a path that had the right number of encounters for that adventuring day. The thing is, though, I’m not going to talk TOO much about the critical path just yet. Because it’s just sort of a line right now. A general sense of where the action should go. It’s just a rough idea. When we start laying out encounters, we’re going to rethink the critical path.

The one thing I did have to figure out though was where the milestones are on the map. And also where the vertical connections are between the levels. So, you’ll see big blocky up/down arrows (triangles) that represent vertical connections between the levels which get turned into dotted lines on the critical path map. And on the critical path map, you’ll see colored circles that represent the “keys” that unlock the color coded areas.

Before we start breaking it all down, here’s the big maps again. Clicking on them will enlarge them in a new window. And now, let’s take a tour of the first ten days of our dungeon adventure.

Day 1 to Day 3: The Adventure Begins

The act of sketching a map like this is not merely an act of laying out physical space. Because the map will ultimately provide the plot and structure for the game and because it will guide the players and because it will tell the story of the adventure, drawing the map entails thinking about a lot of things and making a lot of decisions. And, frankly, the first three days of the adventure involved more thought and decision than any other days. Because they have to set the tone for the adventure. They have to introduce concepts about how the dungeon will work. They have to draw the players into the story. And they have to train the players to think certain ways.

All we know so far about how the story starts is that the heroes are drawn to this place because of a generic hook involving some kobolds. After they deal with the kobolds, they discover the site is a lot more extensive than it seems. And that there is a greater plot going on. So, from a story perspective, we want them to reach a goal, to stop when they reach that goal, and then come back another day. What we need is a quest that is time sensitive – that has a sense of urgency so the players will stop to complete it – but one that goes away once it’s dealt with.

We know these kobolds have been drawn to this site in service of a dragon. And the dragon has been gradually corrupted by the presence of the evil demon. We can assume the kobolds are following the dragon’s orders to search the site for ways to unseal the demon while also doing what kobolds do, looting and pillaging the site. But the kobolds also need supplies. They need food, tools, all of the amenities. So, in the outer area of the site, they have a raiding party. And the raiding party wanders out into the wilderness, hunts, gathers supplies, and brings them back. Suppose the kobold raiders stole something that has to be returned urgently. Maybe the nearby town has been afflicted with a disease? And several people have days to live. The kobold raiders attacked a trader who was bringing medicine from a distant land. When the heroes retrieve the medicine, it is urgent they return it to town immediately and not delay. So, the heroes arrive, defeat the raiding party, are tantalized by the extensive paths they couldn’t explore, return the medicine to town, and then gear up for an expedition.

Of course, the kobolds will have to draw them along a little. They will have to learn that the kobolds serve “someone” and they have a greater plan and they might be dangerous to the local settlement. That will motivate hack-and-slashers and greater-do-gooders. We have to tantalize the party with valuable treasure and magic, to motivate the greedy and power-hungry. We have to imply the site has a complex and interesting history, to motivate the investigators and the archaeologists. And we have to show closed-off paths and unturned stones to motivate the explorers and spelunkers. These things will give the party motivations to return and keep digging.

Now, not only does this story serve as a simple hook for the heroes that creates the structure we need, it also teaches the PLAYERS (not the characters) something about how this game is going to go. And we’ll reinforce. Basically, we want them to understand that it’s okay to break the dungeon down into chunks and make a series of expeditions. And we also teach them to expect solid milestones.

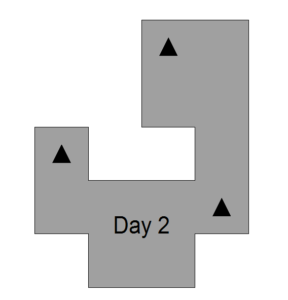

This lesson gets reinforced on day 2. On day 2, the party returns and explores the one path open to them. Conveniently, they become trapped and have to escape. I’ll come back to this idea in a second because we want to work out HOW they get trapped. But for now, just understand that on day 2, we trap them, they find a way out and open a way forward. Not only do they, once again, spend a day adventuring and hit a milestone, they also learn that new paths get opened to them when they explore.

Day 3 builds further on this lesson. Because we want to be repetitive as hell. On Day 3, the party finds the Skeleton Key. That’s their milestone. Day of adventure. Milestone. Open new paths. BUT, they have to backtrack to find the new path. Because it isn’t right in front of them this time.

So, you can see that the first three days of adventure are not just apprentice levels in terms of experience and power, but they are also training levels. These days teach the players the structure of the adventure by repeating it AND by adding lessons to it.

This, kids, is called tutorializing. You teach the players the behaviors you want by forcing them (gently) to behave that way until they internalize it. We’re going to do A LOT of tutorializing in this adventure. Because tutotializing is about empowerment. When you give the players the opportunity to learn how best to play the game and deal with obstacles, you give them the power to earn their own victories and to see how they failed when they failed. From subtle things like conforming to a structure to more overt things like introducing enemy tactics in a controlled way and then creating situations where those tactics can be exploited, everything serves as a lesson for everything else.

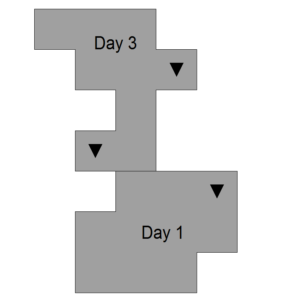

But let’s not jump ahead. Here’s the maps.

Day 1 is pretty simple. It’s just a nice little isolated chunk of dungeon with a pretty short, direct critical path and one or two side rooms. Chase the kobolds, find the kobolds, get the medicine. And, conveniently, the kobold camp is precisely where the passage to day 2 is. So we give them a place to come back to.

And this, by the way, enables another lesson. When the players return on day 2, they will run into a random encounter or two. Minor vermin that have filled in some of the spaces the kobolds have cleared. They will learn that the dungeon is alive and things wander in it.

Now, day 2 will build on THAT lesson. On day 2, the party falls into the crypts. And they have to escape. And by escaping, they have to open previously sealed passages into the crypts. We’re going to force them to do that. And once the crypts are open, undead are now free to wander the site. When the party returns, maybe on day 3 or maybe later, they will start to have random encounters with the undead. That will teach them that their actions change the dungeon. They should realize (if we play it up right) that they unsealed the undead and allowed them to escape. This will actually also form a story arc that ends many, many days later when they finally destroy the corrupted spirit.

And thus, in three days of adventure, we teach the players all of the major structural elements of the game. Exploring in chunks, hitting milestones, backtracking to previously inaccessible areas, wandering encounters, and how their actions affect the encounters they have.

But, the funny thing is, none of that really requires anything special of the map. The map could be shaped like anything to accomplish those goals. So we can pretty much just lay out boxes. Right? Mostly, yes. I bet you were expecting me to say “well, no… not really because of reasons.” But, right now, the shape of the dungeon itself doesn’t matter much.

But what’s interesting is we can also start thinking about the different regions of the dungeon. Because, in addition to introducing the cast of characters (kobolds, undead, elven builders) and the structure of the game, we also want to start introducing the geography of the site. And that means, as I’m drawing, I’m also thinking a little about the layout of the place and maybe the history.

The first day takes place in the Desiccated Sanctuary. I chose those words partly because they were cool and partly because they were evocative of the Chozo Ruins area of Metroid Prime. And Metroid Prime did more to make me want to create this dungeon than anything. A sanctuary is a place of safety. A place of retreat. Maybe a place of providence. But it is also a place of peace. Desiccated means dried out, devoid of life, dehydrated. But the Desiccated bit is new. It wasn’t always that way. There was water here. And life.

Why would elves build an underground complex? That’s the tricky question. After all, that’s a dwarf thing. The place would have to be pretty special. And it was. On the other side of this mountain is a volcanic crater, fertile, teaming with life, and home to a giant tree. If the elves discovered that, it would seem like a holy site. But still, there has to be more to it than that. What were they even DOING here? What IS the tantalizing mystery?

Well, we already mentioned dwarves. What if this particular group of elves had an alliance with dwarves? Not just a grudging trade agreement or anything like that. What if a group of martial elves had been in the mountains because they were giving military support to their dwarven friends. Perhaps against the giants. In some ancient war. A detachment of elves was routed and driven into a mountain pass. There, they found a series of natural tunnels and hid to recover their strength. And in wandering the tunnels, they discovered the Great Tree. What a providence from the elven gods, right?

So, they began to build a sanctuary. Once the giant wars were over, elven missionaries came to the site. They started by improving some of the caves and forested grottoes. And, while they received assistance from their dwarven friends, they did it in an elven way. They added art and sculpture to the natural tunnels and carved out open patios and meditation spaces and weird half-underground gardens and waterways. Places to wander and contemplate a different form of natural splendor. Water and stone and the mighty plants that can split the stone and draw the water from the cracks. They build waterways and canals and galleries.

And THAT is the Desiccated Sanctuary. It is the dried out, sand filled, husk of those first spaces the elves made. With the water gone, the plants withered and petrified. The channels became choked with sand and rubble. The air dried. And it became tan and gray and dead.

So, the Desiccated Sanctuary is a mix of constructed spaces, natural tunnels and grottoes, many of which are probably open to the sky, and improved tunnels with pathways and gardens and sculptures. And there, they commemorate part of their historical friendship with the dwarves.

The Crypt of the Ageless is also odd. Elves live for such a long period of time and they probably reproduce very slowly. So crypts would be unusual for them. Extensive crypts, anyway. Unless, of course, they were at war. So, much of the Crypt would be filled with memorials to elven soldiers and bladesingers and warmages who fell against the giants and their orcish allies to help drive them from the mountains and also serve as a bulwark for the elves of the valleys beyond. When an elf dies violently, so much is lost. So many centuries are left unlived. Every elven death is a tragedy worth commemorating. There are no simple shelves or ossuaries filled with the dead. Their chambers are memorials and remembrances.

Finally, day 3 introduces the Sacred Halls. We have to assume that, after the giant wars were over, elven missionaries and scholars retreated here to contemplate the singular wonder of this place. And so, they began construct new halls, probably more akin to other underground structures, though beautiful in their own way. And that is how they discovered the strange Crystalline Caverns beneath the site. And they discovered the mysterious magical ore. And so, workspaces and libraries and mana-forges were built to extract the secrets of the strange magic beneath the place. They also would have discovered the mystical source of water, a rift to the Elemental Planes, above the site.

So, we think about these things while we’re mapping. Day 1 is just simple boxes because it needs to be a straightforward little dungeon, nothing more.

It’s day 2 and day 3 that make things complicated. Specifically, we need to create a situation in which the players can become trapped in day 2 and, by escaping, open the way to day 3.

Between day 1 and day 3, we need a couple of one-way doors. Doors that can only be opened from the back. And, at these experience levels, it’s easy enough to accomplish with stout doors that are barred. That is to say, they are not merely locked, but they are solid metal bars behind them, securing them, that must be physically removed. Day 2 allows the party to come out BEHIND these doors. Opening the way back.

We have to assume the kobolds have some way to get in and out of the site. So, wherever the kobold encampment at the end of day 1 is, there is a hallway that leads deeper into the site. Now, we have a site that is seismically active. We’re not above a little railroading at this stage of the game. So, when the party explores this long hallway, an earthquake strikes. To make it NOT SEEM like a complete screwjob, we can ensure that the place is constantly rumbling with minor tremors. During day 1, the party will experience one or two tremors as they explore.

The floor falls out from under them, depositing them in the lower level and completely collapsing the kobold passage. From there, they can find the stairs up to day 3 that allows them to unbar the big doors and open the way from day 1 to day 3. The actual corridor that will collapse is not pictured on the map or the critical path. It’s just a spot for the event to happen and, in the end, it is completely impassable.

However, as I’m thinking about it, I’m a little worried about locking the PCs in the dungeon. That can be EXTREMELY dangerous. If they are overextended or have a few bad fights, they can’t retreat and recover. That could murder some parties. So, I consider two options. First of all, the room they are deposited in is somehow “safe.” That is, it’s difficult for enemies to enter and therefore the party can retreat there to rest. Due to the cave in, perhaps, the party can only exit the room with a very tight squeeze. With the right precautions, the PCs can rest here. The second thing is that I split the critical path. And you’ll notice this on the critical path map.

Basically, I’m envisioning TWO one-way doors between day 1 and day 3. If the party goes west from the start of day 2, they find the first door, the outer door. And they can easily escape. If they go north (and we’re going to use some map trickery to PULL THEM west, but that’s a story for another time), they can find the inner door, and open the way forward to day 3.

The split critical path combined with the opportunity to rest should serve as a safety net for a low level party. In point of fact, if they are badly injured by the collapse, they might be FORCED to rest. That way, we can teach them that they will occasionally find safe rooms they can fortify in an emergency. That won’t be common, but it is a good to give them a safety net. We’ll have to think more about that mechanic though.

Day 4 and Day 5: Introducing the Great Tree

Days 4 and 5 begin after the party discovers the Skeleton Key and they can now go back to a door they couldn’t open in day 1. And we’re doing a couple of things here. There’s a reason why we placed day 4 where we did.

Notice that the locked door to day 4 begins in the same kobold room where the party found the corridor that collapsed to day 2. This isn’t an accident. First of all, once the party defeats the kobolds, they are going to stop going adventuring for the day. But they are going to remember that that room had TWO exits. Because that’s what they will make a beeline for when they come back. Hopefully, when they find the key, they will remember the lock because they discovered it just as they were moving from goal-oriented mode (kill the kobolds, get the medicine) to exploration mode (I wonder where these doors and hallways go).

The other reason to draw them to THAT particular place is so that they can see that the hallway they collapsed is truly caved in and impassable. Again, we want to emphasize the fact that this dungeon will change as they explore it.

Now, day 4 does something interesting. It lacks a nice hard milestone. The transition from day 4 to day 5 simply reflects passing through the Sacred Halls to the Great Tree. Because day 5 introduces the Great Tree. Now that we’ve taught the players to explore in terms of days and to expect milestones, we’re going to take the milestones away a little bit. That is to say, we’re going to be subtler. You killed the kobolds! You escaped the crypt! You find the magical key! Those are hard, solid milestones. “Hey, there’s more to explore this way,” is hardly a milestone at all. It’s just a transition. Now that we’ve trained the party to think in terms of short forays into the dungeon, we’re going to give them the chance to pick their own milestone. Basically, we’re letting them off the leash now. They might decide to push into day 5 a little more. Or day 4 and day 5 might become three days of adventure. And hopefully that will also help them figure out the push and pull of the random encounter system.

But day 5 does have a solid milestone. The Arcane Key allows the party to backtrack and open more of the sacred halls. However, if you look carefully at day 5, you might notice that day 5 is the first day that has a LOT of encounter space OFF the critical path. That’s a good thing to follow the whole “set your own pace” lesson with. “Set your own pace, also, feel free to wander a bit.” Day 5 is less linear than the other days.

Of course, we’re also thinking about the Great Tree. You will notice that the Great Tree is less “blocky.” It’s sort of jumbled up and haphazard. Obviously, that’s on purpose. But what does this space LOOK LIKE. It’s not just an outdoor, forested space, because it’s hard to make a dungeon out of that. People can wander too freely in outdoor forested spaces. It’s more like causeways and courtyards and patio spaces and small rooms and open gardens and that kind of thing.

But the Great Tree is also dangerous. Here, the party will start to encounter a new type of enemy. The planetoids that serve the evil super plant. They will be dealing with poison and plant enemy types along with the natural vermin. And these, too, they will start to encounter throughout the dungeon. That help emphasize that, as they explore, they will have a growing roster of enemies. Of course, in a few days, those enemies will be no more.

Day 6 and Day 7: The First REAL Boss Fight

Day 6 is an important day which is not immediately obvious. Day 6 represents the opening of the biggest nexus in the dungeon. Day 6 is the most interconnected day in the dungeon. It leads everywhere. But there’s not a whole lot to say about day 6 beyond that. It is just a big space that sits in the heart of the site and touches absolutely everything. It’s important because it greatly expands the scope of the site. Day 4 and day 5 were about letting up on the rails a little and letting the players set their own pace. Day 6 follows up that lesson with “look how much more there is to explore!”

Again, like day 4 and day 5, there isn’t a HARD milestone between day 6 and day 7 apart from the transition between Sacred Halls and Great Tree. So, the party is once again relied upon to pace themselves. We might provide a rest space in one of the extra rooms in day 6, just in case. We’re really going to have to figure out how rest spaces will play into the wandering monster mechanic.

Day 7 is actually a little more linear, despite being in the Great Tree. And that’s because we’re building toward a major boss fight. The plant monster. The thing that is choking the great tree and whose toxic roots and vines have choked off parts of the dungeon. And this is another important tutorial moment. After this boss fight, two things will happen. First, the dungeon will transform. And second, an enemy type will disappear. The plantoid wandering monsters will be no more.

Day 7 also teaches another important lesson: the idea of coming into an area from a different direction. But there’s another part to that lesson. We also want the players to understand that everything IS connected. This isn’t just a hub-and-spoke design. We ALSO want the party to immediately see the transformation they have wrought. So, somewhere between the critical path on day 7 and the one on day 5, we want to add a root-choked passage. The party will see it on their way to the plant boss and see that it is accessible on the way back. If they peek through it, they will discover it takes them back to an area they already know. Thus, they learn about looking for shortcuts and how the space is interconnected and how the geography and theme tell them which areas are close together.

Ultimately, this simple shortcut presents the players their first real choice of path. Because they want to retreat from the dungeon. They can go through the Sacred Halls via day 6, day 3, and then day 1. Or they can travel through the Great Tree via day 5, through day 4, and then day 1. It’s not a HUGE choice, but it’s the first time they have two paths open to them that they are aware of.

While, the first three days were about guiding the players carefully, the next four days are about letting them OFF the rails without really taking the rails away. It’s a delicate balance between freedom and guidance that will create the play experience we’re hoping for.

It is also worth noting that the critical path shows a couple of the optional encounters, a red room off day 2 and an orange room off day 4. I’ll discuss the placement of optional encounters later. But note that these, two, are about gradually letting players off the rails and rewarding them for wandering.

Day 8 to Day 10: ACTUAL Choice

With the giant plant monster dead, the toxic roots that have blocked off some corners of the dungeon are also gone. And that opens two days to explore. But this times, it’s a little different. When day 4 and 5 got opened, day 4 LED to day 5. When day 6 and 7 got opened, day 6 LED to day 7. But day 8 and day 9 aren’t connected. The party can choose one or the other. And ONE is the right answer.

In theory, the party COULD skip day 8 completely. At least for a while. They have to go there eventually. But, if they choose to go right down to day 9 and day 10, that pulls the plot forward and leaves day 8 behind. And, you know what? We’re going to let them. They MIGHT make that choice. But they’ve earned it. We’ve let them off the rails. While, in the end, day 8 HAS TO be explored because it leads to day 22, they could skip it for a long time. Of course, we ARE going to help them NOT skip it until that much later. But we will come back to that.

For now, understand that we’re willfully allowing the players to f$&% up the critical path. But we do have a safety net in day 22. And we are going to add a second safety net.

But with the idea that day 8 is KINDA optional now, we can do something fun with it. We can add a milestone event that wasn’t really in our plot plan.

See, we’re building up this idea of creature rosters. Sort of by accident. The idea is that different types of encounters and wandering monsters belong to different factions. We’ve got kobolds, plantoids, undead, and general vermin so far. And when the party takes certain actions, that makes certain rosters available to wander the dungeon. Or it removes rosters. Right?

What if day 8 allows the party to remove a roster of creature. What if there’s another faction type that has been around from the beginning that we can take out of the game. Metroid Prime, for example, had the war wasps. And I always liked them because they fit the theme of desiccated, once living ruins. And I have always been a fan of kruthiks and burrowing insects and spiders and creepy crawlies. What if there’s a monster type of insectoids and their hive mind or queen or brooding ground or spawning pit or whatever is inside day 8. They are immune to poison, so they aren’t bothered by the toxic death roots and can wander the dungeon. If the party DOES tackle day 8 early, apart from neat optional treasure, they can also defeat the war wasp kruthik spider burrower beetle beasts and remove them from the dungeon.

This is just an idea now. But notice how this idea is also suggesting a mechanic for wandering encounters. They are drawn from particular rosters. The more rosters that are active, the more likely there are encounters. Events in the dungeon make rosters available or remove them. For example, after the party removes the floodgates, demons might become an available roster since they can spill out of the crystal caves. That will replace the kobolds which have to be defeated to even get to the floodgates.

As for day 10, day 10 introduces a new region, the Flooded Underhalls. And we have to think a bit about what they are like. Because they represent the passage between the Sacred Halls and the Crystalline Caverns, some of them were obviously constructed. And they are probably utilitarian work spaces for the elves digging and mining and construction. But they also represent the tunnels through which the tree’s massive roots have burrowed. And many of the spaces are flooded. In fact, the party might actually to adventure underwater a little before they find the Water Breathing object. This is another trick many games do. They present a problem and make you live with it a little bit before you find the solution. Super Metroid’s water areas were actually the BEST example of this. The passages from Crateria through the Wrecked Ship showed you just what a pain in the ass water was in that game. And then you got the Gravity Suit which negated Samus’ weaknesses underwater.

In the end, we have a space like the Sanctuary, partly constructed, partly natural, and shot through with roots. Probably, many of the spaces were built around the roots or were disturbed by the great tree roots. The architecture might even incorporate the roots. And it’s a damp, dripping, flooded, space. It’s the first sign that not everything about this space was once beautiful. After all, even the crypts were beautiful. But this space is ugly and utilitarian without giving up elven aesthetics.

The only part of this that I don’t love is the earthquake that shows up to collapse the hallway JUST as the PC’s are using it, despite that same hallway having had to endure countless previous quakes. Its just too (in)convenient.

Maybe instead of a random quake, the kobolds have a means of collapsing the floor. Maybe their queen is a sorceress with a spell that can shatter stone. Have her meet the PC’s at the crumbling hallway and send them plunging to what she hopes will be their deaths by undead.

In addition to feeling less arbitrary, this would also introduce an antagonist and make the players really hate her, so they’ll be driven to hunt the queen down and kill her on day 9. It could also serve as an early telegraphing of how the queen fights; the players know that she can collapse ceilings and open pits, and if they’re smart they’ll be prepared for that when they next encounter her.

As for why the kobolds would be willing to collapse their own hallway? Simple. They have an alternate pathway through day 8 (since they’re immune to poison), and some way of keeping themselves safe from the kruthikwaspbeetles. Collapsing that hallway is only a minor inconvenience for them that will rid them of a dangerous group of armed intruders.

It’s not at all the problem you think it is. And it is also greatly foreshadowed.

Having the Kobolds deliberately drop the PCs into the crypt causes its own problems. The only way through the red door is with the skeleton key, and the only way the PCs have of reaching it is by falling into the crypt. I assume the Kobolds don’t need the key to bypass the door – they know an alternative way around. Therefore, if the Kobolds don’t know about the key, or don’t care, then having the Kobolds drop the PCs into the only position in which they could retrieve it is really just as random as if an earthquake did it.

The earthquake doesn’t have to be a random event. It could be the work of the final boss trying to lure the PCs into the dungeon to trick them into freeing it from its prison.

@Angry: What do you mean? I’m guessing by your reaction that you have something else in mind that mitigates/justifies the apparent contrivance.

@nige22: Not really. Firstly, because the kobolds have a reason to collapse that specific floor at that specific time, unlike the random earthquake. Second, if that hallway DIDN’T collapse, the PC’s would still be able to advance into the dungeon via the uncollapsed hallway and eventually find the key.

The final boss causing the earthquake would also solve that problem. If so, the earthquake should be one of several events in that vein.

Or, it is random but completely explainable within the narrative of the adventure.

For instance, Angry wants to have the roots of the plant boss spread throughout the dungeon, creating many barriers. How did the roots get to these places? Growing of course! Perhaps this is the cause of the quakes and the cave in. To drive the point home, and to highlight another aspect of the dungeon (the plant barriers) early, perhaps a root thrusts its way through into the corridor as the floor collapses. Not only does this justify the cave-in but the root, and the spores, also serve to make the corridor above completely impassable even if the PCs decide to get clever with climbing gear, ropes, grappling hooks, etc.

“Root quakes” could become a regular theme and hazard in the dungeon. Perhaps some root barriers appear dynamically rather than having always been there. Roots could emerge during certain fight scenes to change the landscape of the encounter in an interesting way. Root quakes, or new barriers appearing, could also be a feature of the random encounter rosters, provided some guidance was given to the DM not to block off the key escape routes from the dungeon.

And after the roots are destroyed, what then? The roots may actually have been supporting walls and floors. Some of the new routes opened to the PCs may actually be caused by collapses, rather than simply the root dying and allowing access to a corridor it previously blocked. On the other hand, similar collapses could block previously open routes, encouraging PCs to go in certain directions, and try to find new shortcuts.

I like that.

The dungeon is seismically active because it is on a volcano. We will be building up to that throughout the adventure. Long before the heroes get down into the lava levels, they will be expecting lava and earthquakes and things.

But, aside from that, GMs tend to drastically overworry about the appearance of contrivance. It takes only a tiny amount of foreshadowing to remove any sense of contrivance. And players care a lot less about contrivance as long as the adventure is fun.

My point is: it isn’t worth worrying about.

@The Angry GM (next or previous comment, I’m not sure how this is going to be ordered when I post it)

I think that while you are right in saying this, there might be minor contradiction here, or maybe we have misunderstood it. I think that if you have the corridor collapse, then you are training them to expect that to happen later. It may only be one event, but so are all your other examples of training players. If you show them that corridors will collapse at random, it will start up the whole problem of constantly searching for traps- they’ll watch for collapsing ceilings every 10 steps and slow the game down. Unless of course you actually have specific mechanics and tutorials planned to show them not to worry, but still be ready for lava.

I would put some sort of bonus treasure or optional clue in the collapsed hallway, just for the eventuality that at 11th or 12th level the party decides to go excavate it using a Move Earth spell.

I LOVE the idea of removing “rosters” of creatures as an optional goal. It makes a definite impact on the world, it’s a tangible reward, and players get to feel badass and clever for doing it. You seem to be aiming to build in “we outsmarted the game master/designer!” moments, and this is a fantastic example of one.

I think it’s safe to say I’m ready to drop some money on buying this adventure when it’s released.

Me too, and that well have to include getting the 5e books.

I am too. I don’t even run 5e, but so far it is nicely similar enough to Dragon Age that I think it would need only minimal fiddling to adjust it to fit the lore. And in a couple years I will be in need of an epic adventure involving a Great Tree, so I can’t believe my luck. 😀

“Between day 1 and day 3, we need a couple of one-way doors. Doors that can only be opened from the back. And, at these experience levels it’s easy enough to accomplish with stout doors that are barred.”

As long as the doors are made of something other than wood/are magically warded to resist minor damage sources/there is something else in place to discourage attempts to destroy them.

There are actually plenty of ways for 1st level characters to get past a wooden door, no matter how stout it is, If patient and without obvious time pressure (which it doesn’t seem like is a problem at the beginning of Day 2), axes, mundane fire, Acid Splash and Fire Bolt cantrips, etc. will all work eventually. Once enough wood is cleared away it should then be possible to manipulate and remove the metal bars.

Ideally this wouldn’t come up since the players are most likely to go down the path of least resistance and head down the open corridor. But you just never know with some players. They might get it in their heads there must be some valuable treasure sealed behind the door and try and get it before they move on.

Angry said earlier that not all PCs will follow the critical path and that’s ok. If the PCs want to hack their way through the dungeon and ignore the path then eventually they’ll run into some impossible fights, and if they think their way around these fights then more power to them

Oh absolutely, but it doesn’t hurt to make the barriers to doing so as robust as possible! It’s even thematic for this dungeon that the doors be elaborate – We’re talking about an elven ruin here. No doubt if they wanted a door to stay closed they had better ways of doing it than mere wood and metal bars.

One of the things I’ve noticed in explaining all of this is that players ACTUALLY breaking the design is way, way, WAY less common than GM’s panicked imaginings of all the ways players MIGHT break the design.

You people seriously need to calm down a little.

And also, as the author of the adventure, I control how difficult it is to do anything. I’m actually sort of offended that you think I could do this degree of planning and not think to not make the doors out of balsa wood.

Like Players in a dungeon, people always wanna “catch you out” in a possible mistake. 🙂

As always, this is great stuff

The nice part about this particular sequence break is that the players are sneaking from Day 1 into Day 3. Realistically, it should be easy to encourage them (via kobold tracking and the sense of urgency) to avoid that door till Day 2, at which point ‘sequence breaking’ is barely a problem.

Later barriers are far more foreboding and require far more work, risk, and expenditure of resources. Even a sequence break this early establishes that the dungeon gives you multiple paths to unlock stuff, and that the break is not likely to be necessary.

My question here is how do you go about establishing the difference between puzzles in the dungeon and locks you legitimately don’t have the key for yet.

The thing is, players will never have unlimited time in this megadungeon due to the random encounters, plus how it isn’t gamebreaking to get through these sorts of barriers. Part of the goal of having the early skeleton key is to show that there will be easy solutions provided for these problems if players explore what is available to them, so they’ll only sequence break if they really want to… and the dungeon will gladly oblige.

I am curious now how well this would work with a West Marches-style communal game, where you’d keep the same dungeon for whichever group of players gets together for a session (with xp total and key items shared among everyone). You’d lose the clear coherent experience and the tutorial area, but the importance of changing the dungeon itself would be magnified when you know other people could be playing and seeing the impact you made. Not something to do lightly, but could be neat for replay value.

Actually, to me this feels like the one point in the dungeon where the players might have quite a lot of time. The urgency of Day 1 is over. They have just come back for their 2nd adventuring day and dealt with the random encounter backfill of the kobold’s rooms to get to the corridor/locked door junction.

In the hypothetical situation they decide to be stubborn and hack their way through the door, I can’t see a good case for throwing another encounter at them to hurry them along. Why? Because the encounter can only come from one of two directions:

1) from outside the dungeon. This teaches the players that the escape route isn’t always safe. That’s probably a desirable lesson actually, but maybe not this early? At this early point in the dungeon, the DM may not want the PCs getting it into their heads that they may as well keep pushing ahead rather than retreating on the basis that either direction could be equally dangerous.

2) from down the corridor. If I were DMing this adventure I would avoid this because if the monster comes safely down the corridor, then after a short fight the PCs head along it and only THEN does it collapse, it draws attention to the timing and makes it feel more arbitrary/forced.

And since the skeleton key hasn’t been found yet, the PCs have not yet learned the lesson that there will be easier ways to get around barriers.

I do see your point overall though and completely agree. This just seems like an obvious place where the pathing might go a bit wrong. Probably for a small number of parties, or even none, but if a party did do this they are going to be in a lot of danger due to their low level. Since it is quite easy to design the doors in such a way that simple methods will not bypass them, it would be worth doing so to eliminate this risk.

Of course, I only have my inference to suggest that Angry was going to use wooden doors at all (he mentioned metal bars behind the door, but not the material of the door itself). He’s probably way ahead of me on this based on how thorough everything else has been!

I absolutely love the sound of a West Marches style dungeon with the kind of dynamic changes Angry’s going to put into his! Could be really fun. But I think it would have to be a more traditional megadungeon, in the sense that it should be more about exploration and less about plot, otherwise you’re going to end up with some or all of the groups getting less than satisfactory play experiences compared to the ones who luck out and deal with all the plot.

You’re also going to run the risk that just ‘staying there and taking the time to do it the slow way’ is going to eventually draw some random encounters. This especially discourages the loud ways, but will make things difficult (and discourage the PC’s) even if they use a quieter, more reliable method (cantrips).

Dynamite dungeon so far Angry! “We’re not worthy!”… Couldn’t resist…. Another thing that’s fun to do with rosters is rather than just getting rid of specific ones all the time, is to occasionally leave them in but make them benign. Maybe they make friends with one particular family of monsters that belongs to a larger group of enemies, and once they have a certain level of trust between them, the enemy camp becomes a sort of safe-ish place to trade, talk, or even retreat too if they’re chased by something. May not fit the theme of this dungeon particularly but it’s fun to keep in mind. I ran a fun couple sessions wherein the high level PCs ended up staying in the wattle-and-daub home of a troglodyte family. The PCs had originally battled 20 of the things to a bloody bloody draw, and when the smelly monsters realized how badass the party was, they parlayed, telling the PCs about a little Black Dragon problem they’ve been having for decades. The PCs could stay and interact with the one particular family, while hiding from the larger tribe (they had good invisibility magic), all the while trying to overthrow a black dragon. Was a fun couple sessions. And every time they ran into Troglodytes after these events, there was always a chance they would be from the family that actually liked the PCs, and would just leave them alone. It also added a surprise moral element to the game, because the PCs knew that if they were caught, their hosts would branded traitors and slaughtered.

One possible idea along those lines for this dungeon; ice elementals. They’re a constant nuisance in the underhalls until you get the frost key, which can vaporize them instantly and make them irrelevant as a combat threat.

I just wanted to say that never as a player or GM I have experienced such a cool dungeon built on the premise of “You can have a look, but you won’t get to explore this part until much later.” It definitely sounds like fun!

Most megadungeons are mostly based on “You go deeper, there’s more danger” but very little backtracking. At least I don’t remember a product running counter to that expectation. And while there is some of that in here, naturally, the backtracking makes it mostly unique.

Players will bonk their head at several temporary deadends, I guess. But players also know the metagame and will realize at some point that having the keys is very important and might actually be a bit prone to leaving areas aside that are actually more like puzzles. But I guess they can only really leave aside optional rooms, so it won’t create a problem. But maybe up to a full session of scratching heads and “What did we miss?”, I guess.

Anyway, looking forward to each installment of this. 🙂

I’m curious how the backtracking requirement will work with D&D narrative exploration. So much backtracking in a video game dungeon relies on walking past the same locked door over and over again, or having a system provided map with all the locations on it.

D&D generally operates under the expectation that players are drawing their own maps, and there’s a conceit that the DM interprets what the players say without unnecessary descriptive overhead: ‘You head back to the kobold king room’ vs ‘You head back to the {DM’s Description of the Room}’, or worse, ‘You head back, through {Description of Room A}, past {Feature B}, through {Description of Room C, including locked door}, over the {natural feature D}, etc, etc, etc, which is the only way to get locked doors back in front of the players if they miss them the first time, despite the fact that on a daily basis they are walking through the room containing the door as a major feature.

This is something I have been thinking about too. This dungeon is full of rich atmosphere and inspiring details – it’s a large part of why I have come to look forward to these articles even more than the feature articles. It’s just so fun to read about and to imagine. I can’t wait to one day introduce players to this setting… and when I do, I want to make sure that I can constantly remind them of the atmosphere and the excitement of exploration so the game doesn’t become a grind with aimless wandering on the days that lack major objectives.

When players enter a new area to explore, they will pay rapt attention to the details as the GM describes the space. However, I agree that as players move through spaces they have grown familiar with, that description should get shorter. If I were the GM, I certainly wouldn’t want to remind them of every single locked door and blocked passage; I feel that would detract from attempts to build the atmosphere and keep transition scenes brief.

I think Angry will have a couple solutions built in. First, it looks like Angry is planning natural ways to remind players about important passages shortly before they become passable. Second, most of the other locked doors will be optional passages. If the players forget or choose to ignore those, it doesn’t hurt the overall game. In these instances, it can be on the players to draw a crude map of the dungeon and note any passages they didn’t go through originally. Of course, players who want to go back and explore locked doors could simply ask the GM to remind them if there were any unexplored passages in certain spaces.

I think one additional option to remind players of the overall shape and atmosphere of the dungeon, as well as any unexplored passages, would be to have a high quality map that can be shared with the players. I don’t usually use handouts in my games, but I think in this case it would greatly enhance this megadungeon. Since the map naturally breaks up into encounter spaces anyway, each time the players finish exploring an encounter space, it could be added onto the pre-existing map. While it would certainly be nice if the players mapped the dungeon themselves, a more artistic map might capture more of the atmosphere while still retaining information on where the players have and have not explored.

I think this would also help combat people’s concerns about players trying to explore areas that they shouldn’t be able to get to yet. A map with clearly unexplored areas is enticing – instead of wasting time trying to get somewhere that is hard to get to, I think most players would choose to explore passages that readily open to them with the tools on hand.

Really enjoying this series. You could turn this into your first book: “Angry’s Guide to Pragmatic Dungeon Design”.

Like some of the others, I do wonder if clever players would find ways to break into areas they aren’t supposed to go to yet. In those case I guess they’d just get clobbered by the higher level monsters/challenges.

So something has been tickling at my brain, and maybe I missed it. You’ve set up the XP for encounters in tiers, and I’ve read your explanation and it seems like a really cool concept. Then there is the concept of milestones and “bosses”. Looking at your tables, it would feel natural to put “bosses” at the end of tiers. Given the fact that, generally speaking, the first level of the tier will feel more challenging than the third level of the tier, if you put a “boss” that fits in that framework, won’t it lack a little challenge for end of tier characters? I hope that makes sense.

Let me expand. If the boss stays within the xp budget and is at the end of the tier, it’s a smaller challenge. If the boss is in the middle of the tier, it goofs with the tier structure anyways. If you beef up the boss without raising the xp, you cheat the players a reward for a more difficult challenge. If you beef up the boss and the do, you screw with your xp progression.

I think this is covered by the idea that the XP isn’t really based on the creature(s)/obstacles overcome. The XP amounts are kind of an average over the tier and awarded not on a per-obstacle basis but at the end of the session/day/arc/whatever, so he isn’t constrained by having to make the level 5 boss fight the same XP as the level 3 first encounter.

I think?

I know I’m late to the party here, but something keeps nagging in the back of my mind and I need to get it of. It’s the transition from day 1 to day 2.

Presumably the PCs walk into a hallway, it collapses and dumps them into day 2. This hallway is not on the map and that doesn’t sit right with me. Where did the hallway lead? Presumably somewhere near the dragon since the Goblins are linked to the dragon. It is the only way for the Goblins to enter the rest of the complex.

So, to which day does it connect? Looking at the map would suggest day 23. But that would be stupid. So would a connection to day 4 since this would mean that the Goblin would tangle with the plant things.

So, where does the hallway lead? It stuck in my mind and there’s a good chance it’ll stick in my players minds as well. I need to see the exit sometime. It’s something like those stairs. It just doesn’t seem to line up.

I’m still not caught up on these articles, so you may well have given this away in a later post – but that Day 1 layout. That’s the Eagle dungeon from The Legend of Zelda, right?

Anyway, these posts are fantastic. I don’t envy the work you’ve had to do to make this thing fit together physically – it’s astonishing. I thought I wanted to get to work on my own megadungeon, but looking at this I’m not at all ready to tackle it yet.