Happy Megadungeon Monday…

EDIT: All right, technically I did manage to post this late Monday. But I don’t feel like changing the introduction. So pretend it didn’t get posted until Tuesday to make the joke work. -AGM

I know some of you are saying that it isn’t Monday. The problem is, there’s no such thing as Monday. Monday isn’t a thing. It isn’t some sort of intrinsic property of certain days. It’s a label. A designation. It doesn’t mean anything except in terms of Sunday and Tuesday and the broader concept of week. And these designations have no meaning except in terms of themselves. They aren’t based on any particular astronomical cycles, for example. Sure, they are derived from terms that have some close approximations to certain astronomical cycles, but even those are hazy. Hell, by sheer virtue of the fact that we’re correcting our calendar by an entire day every four years except every 200th year, Monday is all over the place.

Besides, I’m finishing this article on Monday. So it counts.

Besides, shut up.

The thing is, sometimes, in the design process, it becomes necessary for you to scrap a bunch of work when you realize it’s just not working. So, we’re starting over from scratch. Back to spreadsheets.

Hahaha. Just kidding. Wouldn’t THAT be hilarious. No. We’re not back at square one. Honestly, we’re not back anywhere because the work that I ended up scrapping is the work that came between last week and this week. And I’ll explain that in a bit. The new work was also kind of a f$&% up. I’ll also explain that in a bit. And if you’re wondering how it’s possible for me to f$&% up at all at this point, I’ll also explain that in a bit. Because first, my last article about the size of encounters seems to have ruffled a few feathers. I didn’t explain some things very well and some people in the comments also freaked the f$&% out about certain assumptions I made. Mainly because they aren’t used to thinking through a problem. So, before we talk about f$&% ups, scrapped work, and new plans, let’s look at a few things that came up in comments, e-mails, Twitters, and Facebook messages last week. Incidentally, if you’ve got a comment about an article I post, that’s why there’s a comment section. Unless you’re sending something in based on specific instructions (like Ask Angry or Patreon e-mails), don’t e-mail me. I keep getting inundated by people who want to comment on my posts in sort of a private, buddy-buddy e-mail way. I don’t do that. Also, Facebook messenger? No. I don’t do that either. You want to comment, comment. It’s just too f$&%ing much.

The Size of Encounters

Last week, I started with the idea that I wanted to know how much size to set aside for each encounter. I was sort of curious how big an encounter had to be. And I started with a simple set of assumptions. You need a place for each hero and baddie to stand and you need enough space for them to move around. I visualized a space in which 6 heroes stood on one side, 6 to 18 baddies stood on the other side, and there were 6 squares of space between them. And that gave me a rough count of the minimum for an encounter being 48 squares (6 x 8 squares). I then rounded it up to 8 x 8.

Many people pointed out that I had designed the most boring f$&%ing encounter space ever. Heroes on one side, baddies on the other, and a space in between. But what those people failed to realize is I was just counting squares. It was just a way of listing what space was needed on the battlefield. People pointed out that you could have ambushes where the heroes start in the center and the enemies start around them. Or that the enemies could start in the middle. Or the heroes might enter through a chokepoint. And so might the enemies.

And that’s ALL true. Hell, I am literally the guy who wrote the book-length blog entries on designing those sorts of encounters. But I was just counting squares. In the end, it doesn’t matter if the heroes six squares are on one side of a room or around a doorway or in the middle of the room. They still take up six squares. Likewise, the monsters can start one a side of the room or in two corners or in the middle or around a doorway or scattered around the entire goddamned space. They still need spaces to stand in and that will still be about 6 to 18 squares. The rest of the space will be open for movement. And the minimum amount of space needed for movement to keep a fight interesting and dynamic is about 36 squares.

The thing is, when you think through a question, it helps to break it down into some simple assumptions and find a systematic way to analyze things. And that’s all I was doing. I was trying to count total squares of space and I figured out how many squares I needed to do the three jobs that squares have: space for movement, space for heroes, space for baddies.

Terrain Elements

The next thing that got pointed out was that floor space was not the only thing that filled the space of an encounter. A few folks pointed out that an encounter space could be subdivided by walls, barricades, pillars, chokepoints, and so on. There might be trees, rubble, pits, or other blockades. If you want to get really technical, an encounter space could involve three or four interconnected rooms and hallways and stuff. And I’m not discounting any of that. But these things are subtractive elements. They represent negative space.

What do I mean by subtractive elements and negative space? I mean that you can think of them as elements that chew up space in an existing encounter. For example, take an 8 square x 8 square room. Imagine a 1 square wide wall runs through the middle of it. I’ve removed 8 squares from the encounter, right? That’s 8 squares of impassable terrain. Of course, we need a door through the wall, so that will add one or two squares back. So maybe I lose 6 squares of encounter floor space. Let’s say I add a 2 square by 2 square pit. I’m chewing up 4 squares of space.

Should I expand the floor space to account for those? For example, with the wall, should my encounter space actually be 8 squares by 9 squares? If I add two pits or two wide pillars, do I need to up the space to 8 squares by 10 squares?

You COULD. But there’s no reason you SHOULD. And frankly, it’d create some problems. Let me explain.

First of all, look again at the assumptions behind the 8 squares by 8 squares. First of all, I decided to have space for anywhere between 6 and 18 enemies (which would also allow for large enemies). Realistically speaking that’s a pretty liberal estimate. An encounter with three goblins is going to leave 15 squares of unused space. And most encounters will probably fall in the range of 3 to 6 enemies. So I’ve already got a lot of wiggle room for terrain. And even then, if you really do the math, you’ll find that I’ve used 60 squares. But 8 squares by 8 squares is 64 squares. So I overestimated there too.

Second of all, in the end, the purpose of all of this was to budget space for each area of the dungeon. If you’re building a cute little dungeon with five rooms and a clan of a goblins, you can pretty much just doodle one room at a time and have a dungeon. If we try that crap of building this dungeon one room at a time, we’re going to be f$&%ed nine ways from the day we’re arbitrarily calling Sunday. If everything doesn’t line up between Day 3, Day 4, Day 5, Day 6, and Day 7, we’re going to discover that Day 11 and Day 25 don’t fit into the space between those areas. But we won’t discover that until we’ve drawn more than a hundred freaking rooms, more than likely.

So we have to set a budget for space. Day 3 gets this much space. Day 7 this much. Day 25 gets so much space. And then we draw the dungeon into those spaces. That was the point of everything we did. That way we can figure out the scale for a given day.

So what if we overestimate? Why not just assume every encounter needs 20 squares of budget. We can draw smaller encounter areas inside those 20 squares or use lots of terrain or add long connecting hallways to fudge all the connections. Yeah. And we could also punch ourselves repeatedly in the face. But that wouldn’t be a good idea either.

Over allocating space is dangerous for a few reasons. First of all, an encounter space that is too large is a big problem. We talked about visibility issues last week. And those are just the first problem with overly large spaces. Spaces in which it takes too many rounds to move between interesting terrain elements or with too much space between foes see rounds chewed up by movement. And most players (and most GMs playing monsters) tend not to move once the battle lines are drawn unless there’s something interesting they can do in ONE move. You can add interesting terrain that magically heals creatures or obvious traps you can lure foes into, but if there’s too much space between them, players won’t use them. They will plant themselves and slug away. Too much space is as bad for an encounter as too little.

But what about connecting hallways? We can just have long connecting corridors between spaces to fudge all the space, right? Well, we can, but there’s good reasons not too. Even though every hallway is only one sentence of narration long, long hallways pose some practical problems. Remember, we’re going to have to put maps of this place on a piece of a paper. Or several pieces of paper. Or on a poster map. We’re not just thinking like a GM here. We’re also thinking like we want to publish this. Vast stretches of empty space filled only with long connecting corridors are a waste of paper. That drives up the space it takes up in a physical product and printing costs. Even now, this place is already going to be huge. So we’ve got to work not to make it unnecessarily huge.

The other reason to keep things from getting too big is because the flowchart of the critical path is boring. What do I mean? Things aren’t very interconnected. There’s a lot of backtracking from one part of the flowchart to another. If you’ve ever played Super Metroid though, you might have noticed that, by the end of the game, you’ve discovered how interconnected everything actually is. You’re constantly discovering new paths from one region to another. While you COULD draw a simple flowchart of Super Metroid, it doesn’t tell the whole story.

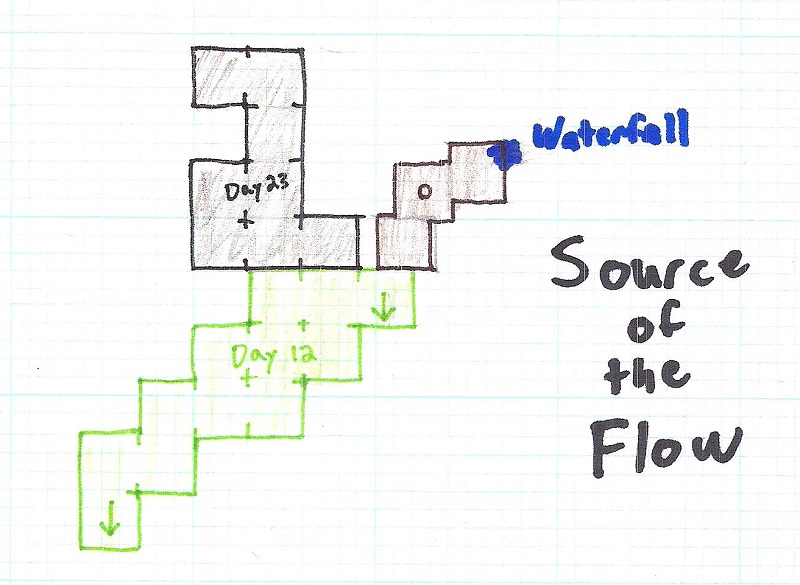

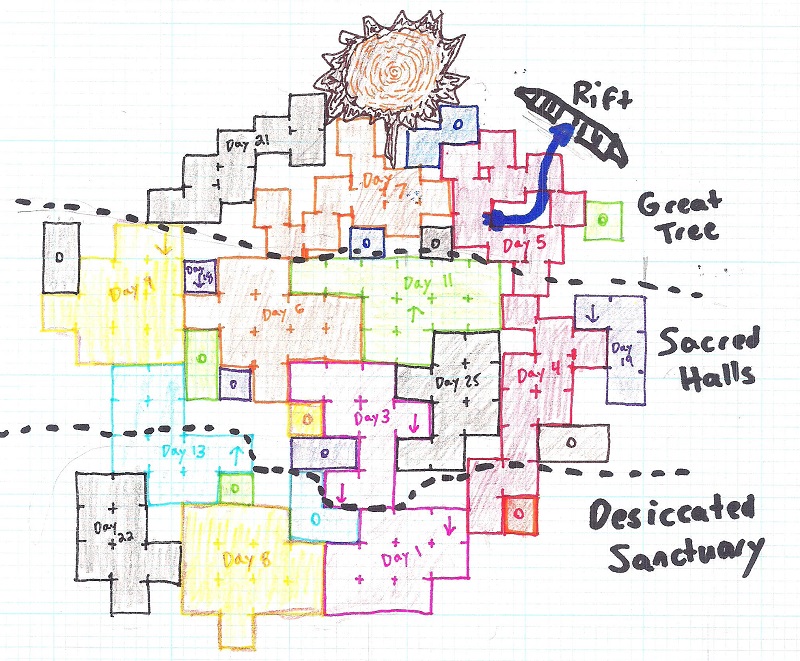

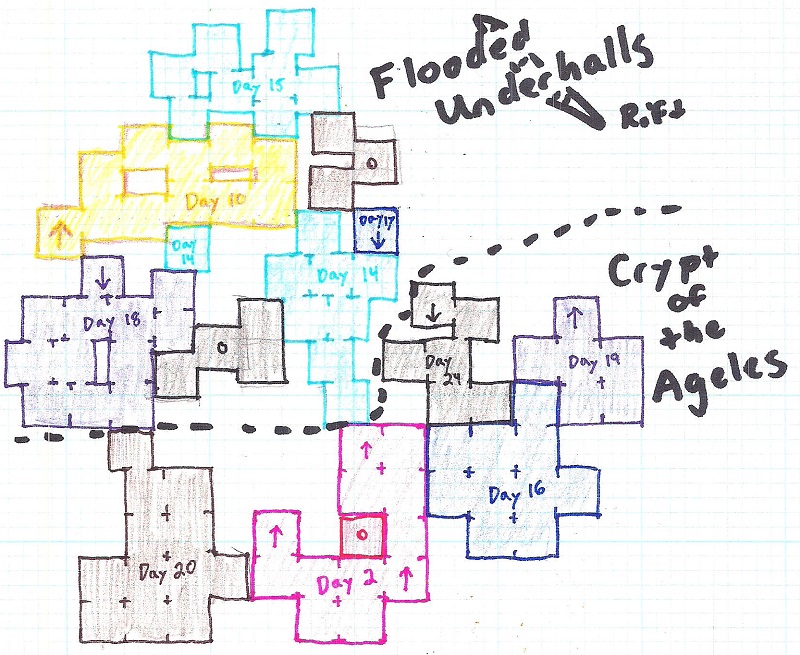

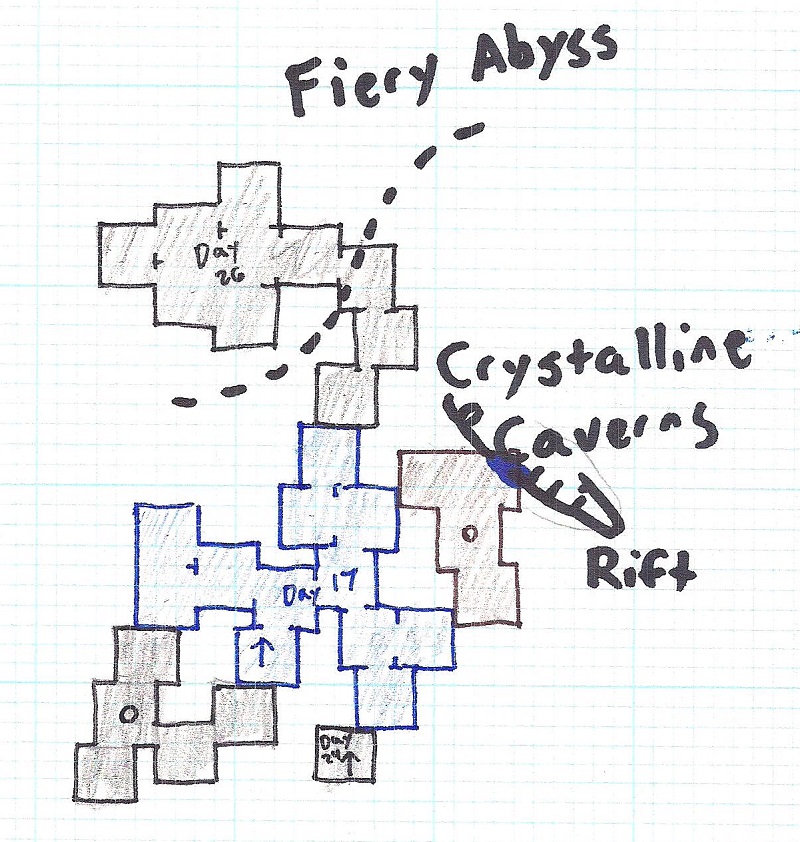

If we constrain the size of the dungeon and make it only as big as necessary and we cram everything tightly together, we’ll start to see how the areas of the different days are butting up against one another, we might discover that Day 22 butts right up to both Day 8 and Day 13, providing multiple ways to access it. We might discover that the optional encounters that hang off Day 11 might actually be spaces in the Great Tree only accessible from the Sacred Halls, like overlooks and balconies. We might discover a waterfall that flows from the Source of the Flow to the Great Tree. These sorts of interconnections in features are VITAL to making the dungeon NOT FEEL like a series of miniature dungeons butting up together.

Tightly honeycombed dungeons with contiguous features and understandable relationships between the spaces are preferable to blank spaces filled with distant rooms connected by long boring passages.

The Shape of Encounters

At this point, I’ve probably explain enough so that I don’t have to address this one. But some folks also pointed out that rooms and spaces don’t have to be squares. Yes. You’re right. We can have ovals, caves, multiple squares connected by passages, L-shapes, H-shapes, whatever we want. And again, that comes from just subtracting chunks from our spaces. In general, the more complicated the shape, the larger the initial encounter from which we will subtract squares. But that doesn’t always have to be the case. Realistically speaking, an encounter actually CAN be smaller than 8 squares by 8 squares. We could probably get away with encounters as small 40 squares and be as irregular as we want.

Lighting

Finally, some people objected to my comments about lighting. And a lot of this comes from the fact that people are kind of stupid about lighting. But what really drives me crazy is the “all or nothing” attitude most gamers nowadays seem to have. I said most underground spaces are mostly unlit and some of the objections raised were “do you mean that there will be absolutely no lightning anywhere in your dungeon? Haven’t you heard of torches of phosphorescent moss?” Yes. I have heard of those things. And yes, some of the spaces in the dungeon WILL be lit. Hell, I have areas that are DEFINED as OUTDOOR AREAS. It’d be really hard for me to make those unlit, wouldn’t it?

But, here’s the thing, most GMs are terrified of the dark. It’s hard to handle, it’s a pain, they don’t want to be bothered. I’ve already talked about what that’s kind of dumb in another article. The point is, I’m CHOOSING to make lighting an issue in my dungeon. It is another element of exploration. Limited lighting is actually tremendously convenient. It breaks up the dungeon so that the players have a hard time peering from one encounter space into the next. It limits how many things are on screen at a time. The GM only has to describe the things that the players can see at any given moment. And if they want to know what’s around the corner, they have to walk the hell around the corner to see.

Lighting is also important because characters with darkvision who take advantage of that darkvision (say, by scouting without a light source) feel good about that choice. And running a game is all about empowering the players to use their tools to solve problems.

Long story short: most of the dungeon is unlit. For good reason. I don’t need to contrive a thousand bulls$&% reasons to light every goddamned room.

Beyond that, some people took issue with my pronouncement that 12 squares was the starting distance for an encounter because, beyond that distance, the forces couldn’t see each other. Apart from the aforementioned “lit” areas, it was pointed out that monsters COULD see the PCs coming from much farther away because the PCs would have light sources. And yes, that is true. But an ENCOUNTER can’t start at that distance because an encounter begins when both sides become aware of each other. Realistically speaking, I could arm a group of goblins with shortbows and put them at the end of a 30 square hallway. They would just start firing into the light. First of all, the goblins would be at a disadvantage that D&D doesn’t model at all. According to strict D&D rules, the goblins could perfectly precisely target any PC. But in reality, if someone is coming down a 150 hallway waving a flashlight in front of them, I can’t really see them. I can see the light. And I should, strictly, have disadvantage because I’d be firing blindly at the light hoping I don’t shoot past the target. And at that distance, it only takes a couple of degrees of deviation to miss a three-foot-wide target in a horizontal plane (which is also why real people don’t hold their guns SIDEWAYS when they fire).

The truth is, D&D doesn’t handle lighting well enough to start getting into more complicated situations than “everyone is in the same bright light, dim light, or darkness.” And D&D also doesn’t handle situations in which one force is completely unaware of or unable to target another force for more than the first initiative pass. Which is why encounters start when both sides are aware of each other and then we determine surprise and roll initiative.

Beyond that, that encounter is terrible. Imagine being a player trying to close the distance with a bunch of archers 150 feet away that they can’t see while being peppered with arrows. There’s not really an interesting way to engage that situation. It’s either charge or flee. And you just have to suck up the damage you take.

So, no, you really CAN’T start an encounter more than 60 feet away in an unlit space. Not if you don’t want it to suck. And that’s why I won’t do it.

The Birth of a Megadungeon: The True and Real History of This Project

So, now, let’s talk about scrapped work. Because I threw out a crapton of work over the weekend and started fresh. And honestly, I wasn’t going to talk about this part. But it is just as much a part of the design process as any other part. Throwing out garbage, realizing you’re doing things the stupid way, recognizing your f$&% ups, and coming up with a new plan. It’s a thing you have to accept if you’re going to create anything ever. And since this is technically a design blog, it’d be disingenuous NOT to talk about the failed attempt.

What you have to understand is that the megadungeon used to be a very different project. And, look, if you want to get to the useful design stuff, you can skip this section. Honestly, if you don’t want to read about failed designs and new plans, you can stop reading here and wait for next week. So, if you want off this article, I’ll see you next Monday.

I started working on it in January of last year. See, I’m not quite oldschool enough to have been a part of D&D during the days of things like Greyhawk and the original Undermountain boxed set. By the time I got seriously into D&D, D&D was starting to change away from the concept of slogging through the same endless dungeon week after week. There was a focus on shorter adventures with storylines that connected together. Honestly, story in D&D was in a weird place. And you could see the argument most strongly in how often Dungeon Magazine – which used to publish the best reader submitted adventure modules – updated its design guidelines and the change in tone. More and more, editorial advice was appearing in the submission guidelines suggesting things like “not using riddles or puzzles that don’t connect to the space or the story” or “don’t have insane opponents, thinking opponents are better” and stuff like that. The adventurers that were getting published were getting more interesting.

You also heard the argument played out between GMs in the game shops. You’d argue about dungeon crawling vs. good stories. The pendulum swung away from dungeons. A sort of elitism grew up around not running dungeons because the game was all about the story. And, hell, I was much an elitist as anyone else. I converted Isle of Dread – based on a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode – into a weird, dark suspense game wherein the solo player gradually discovered he was psychically trapped in his mind which was collapsing around him and the different aspects of the adventure represented different parts of psyche. That must have been around 1995. I was also trying to convince people to play Planescape. Sure, when I started in 1988, I was drawing dungeons on graph paper. But after a couple of years, I graduated from that crap into real games.

The point is, I missed the megadungeon era, but I didn’t realize how much I wanted to run one until I became more sophisticated and critical about video games. Thanks to the magic of emulators, I rediscovered old video games I’d loved like Super Metroid and Legend of Zelda. When I was younger, all my RPG inspiration came from Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest and Crono Trigger. RPGs. Seems obvious, right? But as I started thinking more critical (over the last ten years or so) about RPGs and video games, I realized those were actually really terrible inspirations for games. I also found myself bored by games that lacked fun game-play elements. Turn-based combats and piloting characters between prewritten cut scenes was NOT fun game-play anymore. It was really my experience with Metroid Prime (which I didn’t play when it was first released) and replaying Super Metroid that got me thinking about other ways to engage with a game. Gameplay, sure. But exploration. Discovering the story through gameplay. The ending of Super Metroid, for example, was a masterwork of telling a story without a single word of dialogue or exposition.

Anyway, from the time D&D 4E came out (around 2008), I wanted to run a really great megadungeon. Not just an oldschool romp through every beast in the Monster Manual. A GOOD one. I wanted to do Metroid proud. And a bunch of other games to a lesser extent. But I’m lazy as f$&%. Seriously. And I could never convince myself to sit down and design an entire megadungeon. And it seemed like the sort of thing you had to have pretty much finished in advance if you wanted to do it right.

So, it never got done.

But in January of last year, I started thinking seriously about whether it was possible to design and run a really good megadungeon without having to design the whole damned thing before the first day of adventure. Could you plan it well enough that you could design it just a step or two ahead of the players? And that’s precisely what I set out to do.

All the crap about space allocation and budgeting and planning out a flowchart to show the relationship between areas, the very idea of breaking the dungeon down into days of adventure and carefully controlling the traffic flow? All of that was to facilitate building and stocking a dungeon a week or two in advance of the players.

And so, I started to do exactly that. I planned out the spreadsheets and the story and the flowchart. Basically, everything we’ve done up until now, I had done a year ago. But I was an accountant at the time. And from January to April, if you’re an accountant, your life stops. So, I started doing spreadsheets and flowcharts and stuff to start preplanning in my few lucid hours between doing tax returns. The plan was to celebrate my return to real life on April 16 by starting up this game. And I did. I ran the first two days of adventure over the course of three sessions. And I was designing the adventure one step ahead of the players.

And then my life fell apart. I had a lot of high hopes for rebranding my website, publishing content, and doing all sorts of cool things. And a conflict with my employer destroyed everything. As a result of new conflict of interest regulations for those in the financial services industries, I could not participate in crowd funding endeavors. My living situation also fell apart and I found myself potentially without a place to live. Ultimately, that’s how I ended up with a Patreon and moving from New York to Chicago. And, as part of the Patreon thing, I thought it would be fun to continue building the megadungeon project once life settled down. I had basically designed a scheme for building it as you go, so instead of building it as I ran it, it seemed easy enough to build it as I blogged it.

But, during a problem with Google and transferring my account between user names, I unknowingly lost all of my data from Google Drive. And shortly after I moved, my apartment was broken into and robbed. And an external hard drive I was using had been taken by the thieves. So everything I had designed for the Megadungeon was gone. Including the backups.

By the way, last year was pretty s$&% all around. My life was a series of disasters.

So, now I found myself in the awful position – because I had already promised the megadungeon – of having to reconstruct everything to keep writing about it. From memory. As best I could. Which means, instead of being months ahead of publishing these articles, I am generally only a week ahead of these articles at the best of times and sometimes I’m not at all.

And THAT is why if I hit a major wall or f$&% up, I’m working overtime to get these articles out.

The reason the Megadungeon went on hiatus after “season 1” was because I realized that building it “one adventure day at a time” was not going to lead to a very good ongoing article series and I had to find a new way to present the whole series. And then to catch up a bit and work s$&% out.

So now, let’s talk about the f$&% up.

Do As I Say, Not As I Did

If I ever tell you something is a terrible mistake, it’s usually because I made that terrible mistake and it was horrible and now I’m trying to keep you from doing the same damned thing. For example, up above, I mentioned how it was a really terrible idea to try to build the dungeon room by room. Because you’d suddenly discover that you can’t make certain days join up and certain rooms fit together. Now, that might sound odd considering that I just got done telling you that my plan was to build the dungeon one day at a time and stay a few steps in front of the PCs.

Way back when I started this a year ago, I was doing exactly that. After I had my flowchart and figured out the basic sizes of encounters, I started building up each day, in order, as a series of “rooms.” I picked a scale and started plonking rooms onto a piece of graph paper for Day 1. And then I would add Day 2 on there. And Day 3. And I had gotten as far as Day 7. Which wasn’t far enough for me to hit a disaster. It was far enough for me to think I’d hit on a pretty good system. Yay me.

So now, as I’m reconstructing the work, I figured I’d do the same basic approach. For example, using the scale of 2 squares of encounter space is 1 square on this grid, here was how I laid out Day 1.

And then, I could add on Day 3 when I got there (because Day 2 is on a lower floor). Just like this.

But the thing is, I decided to just lay out the whole f$&%ing dungeon last week. Just like this. Don’t work one day ahead. Lay out the whole f$&%ing thing. And it’s a good thing I did. Because I kept hitting disasters. I couldn’t make it all fit together dropping one room at a time.

After days of frustration, banging my head against the wall of drawing and redrawing and starting over and trying again, I realized my approach was fundamentally flawed. The problem was, by drawing individual rooms and picking vague sizes and shapes one room at a time and trying to plan a path through each day, it took too much work to discover things weren’t going to fit. I would put down fifty rooms before I discovered I couldn’t fit a connection I needed.

The thing is, I was being impatient. I should have known it was a stupid approach. But I was tired of planning. I wanted to get down to coming up with cool names for rooms and designing fun features. Spreadsheets are flowcharts are fun to a point, but I was getting bored of them. I wanted my dungeon to start resembling a dungeon.

The sad truth is this: if I wasn’t committed to this s$&% on the blog, I’d have given up the project. If it were just personal, I’d have quit. But that isn’t an option now.

Breakthroughs and More Poor Planning

Whenever I’m really stuck with a project, I find it helpful to do one of two things. Either, I remove myself from the project completely and let it sit in my subconscious underbrain and marinate in its own brain juices OR I go back to the inspirations. In this case, I was already doing both. See, recently, I had a lucky break money-wise and decided to replace my stolen Nintendo Wii and the Metroid Prime Trilogy because I couldn’t live with the idea that I’d never play or own those games again (and that I’d never finish Metroid Prime 3: Corruption). So I have been replaying Metroid Prime 2: Echoes. With growing frustration over the megadungeon project, I stepped away from all the balls of crumpled graph paper and decided to shoot the hell out of some f$&%ing Ing and save Planet Aether from Dark Samus. And I just happened to be looking at the game map Saturday afternoon and suddenly, I realized a different approach. The Metroid Prime and Prime 2 map display answered the question. So, I killed Chykka and restored the light of Torvus Bog and then found a save point.

Saturday night, I sat down and said “all right, it’s time to work this the f$&% out.” I grabbed a pencil and some graph paper and started drawing. And it seemed to be working. So I kept at it. And it SEEMED to be good. So I added some more detail. And that worked. And then, I started coloring things and adding a few other things. And, in a flurry of creativity, suddenly, I had something that REALLY worked. It looked good. It looked great. In the end, I knew it had worked because of a waterfall.

And then I was like “all I have to do is explain how I did this to the entire Internet and I’m done.”

There were two problems. The first problem was that, in my creative flurry, I forgot to document the steps. Usually, I take photographs or scans as I’m working longhand so that I can show off particular stages. But I was in a weird creative Zen zone and I was afraid to stop. So suddenly, I had a completed map that would be very difficult to discuss in any sort of step by step way.

The second problem was that, in my creative flurry, a lot just sort of flowed out of me and came together. Party because I DO have a sort of picture in my head of how things should work. Partly because I am good at thinking ahead of myself so I can generally see how future things will fit into current things if I’m not trying to be too detailed. And partly because sometimes s$&% just comes out of your pencil.

I needed time to really look at everything I had done and analyze where everything had ended up before I could explain it to anyone else.

So, I had a finished map I couldn’t really explain. No intermediate steps. No real understanding of how it worked. The only thing I could really write about it was “I figured out this neat way to convert the flowchart into a general map using Metroid Prime’s mapping system. So I did it. Suddenly, I drew the whole dungeon, here it is.”

And that would be a terrible article.

So I realized I would have to find a way to redraw the entire goddamned map while documenting the steps. And in so doing, I would figure out why I made the decisions I did and I could talk about it.

And THAT is why today’s article is about clarifying stuff from last week and also about utter failures. But this story isn’t without lessons. I think it’s valuable.

Lessons Learned

First of all, laziness is actually a useful thing. The desire to do only the minimal amount of work needed to accomplish a goal CAN lead to efficiency. But laziness is a double-edged sword. It can kill a project. Ultimately, you have to separate the unwillingness to do unnecessary work from the unwilling to do any work at all.

Impatience can also be a useful thing. Because sometimes it leads you to jump into stuff you would otherwise overthink. But impatience can also lead you to skipping steps and make careless jumps into things you aren’t ready for.

Impatience and laziness together are always terrible.

You’re going to fail. Eventually, you’re going to f$&% up something. And when that happens, you can keep banging your head against a wall, but eventually, you have to be willing to crumple stuff up and throw it out and go back to the last good thing and start fresh from there.

Waiting for the spirit inspiration won’t get you anywhere. Inspiration is a myth. But if you hit a frustrating wall, you need to remove yourself from working on something to let your brain work on it without the rest of you getting involved. Find something to distract yourself. Work on another project. Go back to something that inspired you in the first place. But don’t actively think about the problem. Your brain WILL keep working on it and new stimuli often help it find connections.

Sometimes you will get into a creative Zen state. Waiting for inspiration is a waste of time, but when inspiration DOES happen and things start flowing out of you, remove yourself from all distractions and just let things pour out of you. You may not understand everything that’s happening. Just go with it. You can analyze later. If your brain is giving you something, don’t get in its way by trying to think too hard.

Next Week…

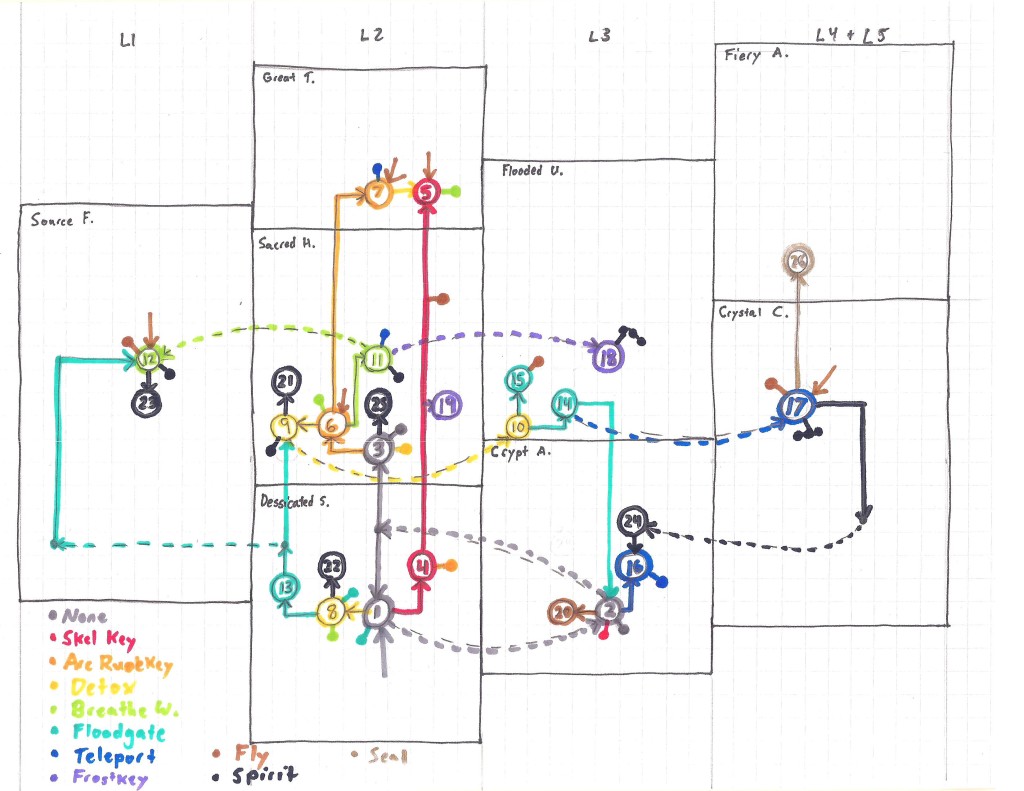

Next week, we’re going to talk about designing the actual map. That is, I’m going to explain how to go from flowchart to this first level of map. But here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to let you play with the problem in your own head a bit. Here’s the map. This is the layout of the megadungeon. All color coded with major features identified. See if you can work out how it got built and why it got built.

I’m also going to give you a few hints and other pieces of the puzzle. First of all, each square on that tiny graph paper represents a space that is 5 squares by 5 squares on a real dungeon map. That in turn means each square 25 feet by 25 feet. Second of all, here’s the flowchart we came up with for the dungeon. Remember that?

Third of all, this is a map screen from Metroid Prime. First, you can see the actual map. Second, you can see what happens when you fully zoom out of the map. THAT is what tipped me off.

Just think about it. Feel free to speculate. See what patterns you notice.

You did a hierarchy of resolution- started with a lower resolution map, filled detail in at that level, then increased the resolution and added detail, possibly multiple times?

This is great. Thank you for being honest about all the steps of the process. And I love the high level view of the whole thing. Can’t wait to see you deconstruct it and build on it further.

You stopped thinking of rooms as floor plans, and started thinking of them as abstract spaces? Thus allowing you to construct a high-level map-flowchart hybrid. When you start designing individual days, only then will you give the rooms shape, and then a final pass to give them the details like terrain features and monster placement. This first pass gives you the sizes, so you know no matter where you start working, as long as the rooms’ outer walls fit exactly within those size limits, everything will match up as intended.

It’s beautiful. It came together very elegantly. And if Rick and derobim are right about how you did it, then no wonder it percolated up or flowed through or whatever, because you’ve been talking about it this whole time. And by this whole time, I mean since about a few weeks ago specifically. But also kind of this whole time with the whole spreadsheets thing. Like, figure out what everything is going to be, then fill it all in once you already know all the tricky stuff because it is all fit to a larger schedule/progression/structure. Heartfelt congratulations to you, Angry.

This means more because you were honest about messing up. Dealing with your mistake (and admitting that you made one and detailing how you dealt with it) is more inspiring and helpful than accepting something that’s done wrong.

Ugh. If I had written the last article and gotten comments like that, it would’ve been “SCREW YOU, INTERNET! I’M OUT!”

Carry on with the good fight.

As Angry’s mentioned before his comments section is one of the most civil. Probably the need to wade through a lengthy article to find the comments section helps 🙂 . But, yeah, commenters can be quite ungenerous sometimes.

Seriously. Angry can be a bit rough on his subject matter sometimes, but I’m glad to find a blog writer with a goddamn backbone for criticism

But it’s not criticism. That’s why it’s so dumb. It’s people saying “But but the theoretical thing that you did doesn’t encompass all these ! Why are you leading me astray?!”

Wow, okay, comments don’t like angle brackets. Good to know.

Anyway, the bit that would’ve driven me up the wall was the people complaining about things that actually WERE part of the solution, or things that weren’t that were deliberately excluded. That’s not “criticism” – at least, not in the sense of “informed critique” it’s people just not reading thoroughly and understanding the intent.

Hexagons are the future!

Seriously, this is a great development. When you started talking about making a gated megadungeon on the fly, I was skeptical. As in “That’s fucking nuts.”. But I do believe this approach would work, If I’m understanding what your approach is now.

The previous map was a scatter of points that were tied together by a tangle of paths. However, the map here is designed from a single root. A path is plotted, then you backtrack and choose a spot to begin a new path, and then you repeat. Not only is it easier to plan, but it forms a more natural path for the adventure. It also feels like your carving into the cavern’s secrets rather than simply meandering. Does Lord Angry demand anything else?

The one thing I’m puzzled about is the blocks with circles in them? Optional encounter spaces perhaps?

Now that you mention it, I think those might be discoveries or treasures. Several are locked behind optional water breathing spaces and Angry already mentioned wanting water breathing to add a bit more since it got shortchanged.

They almost look like reference points to keep the multiple levels aligned.

Yeah that was another thought I had. Definitely looking forward to part #2 🙂

I’m guessing “O” is for Optional?

In my mind you made an 11 square version of Tetris, cut the shapes out of construction paper, then jumbled them around til they sort of fit. This probably didn’t happen, of course, but it’s similar to the mental work I would have been doing.

Also, I’m doing some rough estimates here and, before carving out rooms, you have ~ 25×25×11(conservative average count of squares per day)= 6,875 square feet per day. So this dungeon is going to be around 234,000 and 175,000 square feet without accounting for optional areas, which means that if this dungeon were on the market today in, say, Detroit, which has an average list price of $12 per square foot, everyone in Detroit would be eaten by kobolds.

Also, it would cost about $2,000,000, plus extras for water feature, extensive garden, and indoor pool. I suspect pest control would be quite pricey as well, especially considering travel prices from outside the Detroit metropolitan area, since any local exterminators will have been eaten by kobolds.

This is a rough estimate that doesn’t take into account damages from otherworldly forces, optional encounter areas, rumors of demonic possession, and the long time spent uninhabited, so I imagine negotiations would bring this price down considerably, especially considering the shambling elf corpse clawing at the agent’s door. And I need to find something better to do with my life.

Embrace the darkness.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDH3AoOQzE0

Step 1: Establish a max encounter size and used that to create 15×15 standard encounter modules. Legos.

Step 2: Refer to the Final Plot Spreadsheet and the Flowchart.

Step 3: Be Angry.

Step 4: Embrace the awesome power of your Megadungeon’s fully functional physical framework.

I’m sorry to keep replying to myself but I keep having more thoughts about this.

What if we back the scale up from encounters to days – how many ‘modules’ fit into a day? The minimum is at least the number of encounters that day needs, plus discoveries, plus some breathing room, plus… enough space to make it fit right? To feel right?

During the initial design of a modular layout as illustrated above, how much transparency do you allow each piece in your consideration of it, as far as your vision for what the eventual guts of each piece might look like?

Did that make sense? I don’t talk good

Not too bad for a robot!

I know I already commented above, but I can’t stop thinking about it. I love the shift in thinking toward carving rooms and encounter spaces out of established blocks of day-space. That way, players should be able to have more freedom within and moving between each day, while each room can have its own structure as suits the needs of the plot at that time. Some may be rather linear, others branched or looping, and still others could be more open. As long as they fit into the high-level boundaries, they can be anything within their space and still fulfill the needs of gating, backtracking, and narrative flavor, making the whole feel more unified and coherent.

I love how well they’re all packed in there. I’ll be curious to see if and where you try to add high-level symmetry and strategy to the actual architectural layout, since right now the days are pretty squirmy, but the elves themselves likely used more structure, geometric intentionality, consideration of practicality of use and maybe even intuitive navigation (like airport and mall designers try to do to guide traffic using architecture and light more than signage). The contrast would be very fun to unconsciously feel as a player, moving between intentionally planned spaces (ie the sanctuary and sacred halls), the wilder layout of the tree area and the crystal caverns based on fast and slow growth, and the in-between spaces that were either more organically or expediently built by humanoids or that were originally strategically built but marred by ruin.

I wanted to add more than just “It’s really interesting, keep it up” to the overall discussion, so here goes.

You said that each small square on your graph paper is 5 actual (5ft) squares, and you’ve arranged those small grid squares into blocks of 3×3, which would represent 15×15 squares. I’ll be calling these 15×15 square arrangement blocks from here on in.

I also note from your earlier articles that the huge encounter size is 14×14 so I can only assume this is deliberately done to allow you to do 6x huge encounters with enough extra space for connecting tissue AND those 6 huge encounters can be anywhere in that Day. The blocks themselves connect a Day to another Day, and give you enough breathing room to create your megadungeon on the fly. So long as you stay inside those 15×15 square blocks, it doesn’t really matter what’s inside each day.

Now, you don’t *have* to stay inside one of those 15×15 blocks, but that would be the exception, not the rule. You know the shape of the dungeon, it’s filling in details from here on in.

Those 15×15 blocks are going to have a lot of negative space when he starts converting them into actual floor plans. Connective hallways are going to take a very large chunk out of the available space. Not just that, but the actual shape of the room will too: an L-shaped room, for example, loses an entire large corner worth of space.

Angry has to make all of his “rooms” huge because there has to be a whole lot of breathing room to cut out negative space.

I think you’re right in that if it was 6 rooms and a few connecting corridors there would be a lot of negative space, but I also think that’s why you wouldn’t do that.

The blocks assume the largest space, so a huge encounter could be anywhere. The reserved space also need to communicate narrative information as well.

The Sacred Halls, for example, will act as a bit of a hub, and is the ‘main living quarters’ area for the Elves. So there are going to be lots and lots of non-encounter rooms that need to be there to convey this. Family homes, community centres, small temples to various nature spirits, artisans workshops, centres of trade, that sort of thing.

That’s also leaving out dead ends, optional discoveries, short cuts, safe resting places, small random encounters and other things like that.

I think there’s going to be much more in each area than 1 room for each encounter, because as you pointed out, that would be boring, but there is so much more that needs to be in the dungeon than encounter rooms. Plus, it can always be changed if it does end up with too much negative space, as long as the connections between regions remain.

The sections on Size of Encounters and Terrain Elements leave out some important considerations.

You work on the assumption of counting squares to allow for all the combatants to detect each other at distance and have space to move around. Some encounters should be like that, but others should not.

Remember that big, open spaces favor range combatants, including arcane casters, whereas cramped quarters tdnd to favor melee combatants. So if the encounter is with falchion-wielding orc berserkers, they would prefer tight quarters that don’t allow enemy casters to be more than a move out of reach, whereas some mind flayer sorcerors will want the bigger open space.

Terrain elements also bias combat in a number of ways. Ambush encounters which depend on hiding as defense and sneak attack for offense are enhanced by large spaces with lots of cover elements and concealment. A labyrinth of corridors, a dense forest with massive trees, stalagmites, ruins with partially-collapsed walls all favor ambush encounters, where tight quarters or cavernous empty spaces work much to their disadvantage.

So you should vary up and fit the encounter to the space!

Are you not just re-iterating the same thing that he was ‘debunking’ in those sections?

The whole space excercise was about a rough estimate of how much room you would need, not how that room would be used (obstacles, strategy, tactics, creature size, terrain and so on).

As i see it, his excercise on spacing is a step or two before you actually begin thinking about what’s in the space. It’s a higher level strategic plan, where you are moving around the tactical zoomed in skirmish level. It seems to me Angry was describing how to space out a worlds continents and you are pointing out how people organise their countries or cities… it is simply not relevant yet, to my way of thinking.