I realize that I haven’t actually talked a whole lot about building the setting for a campaign. And I really should. I’m pretty sure I promised I would. I guess I’ll get around to it someday. Cause this ain’t it. Not really.

Welcome back to A Very Angry Campaign, where I check in every few weeks and tell you how I got a dysfunctional, mostly core only Pathfinder campaign off the ground for a bunch of strangers without any sort of plan whatsoever. In other words, how campaign building REALLY goes.

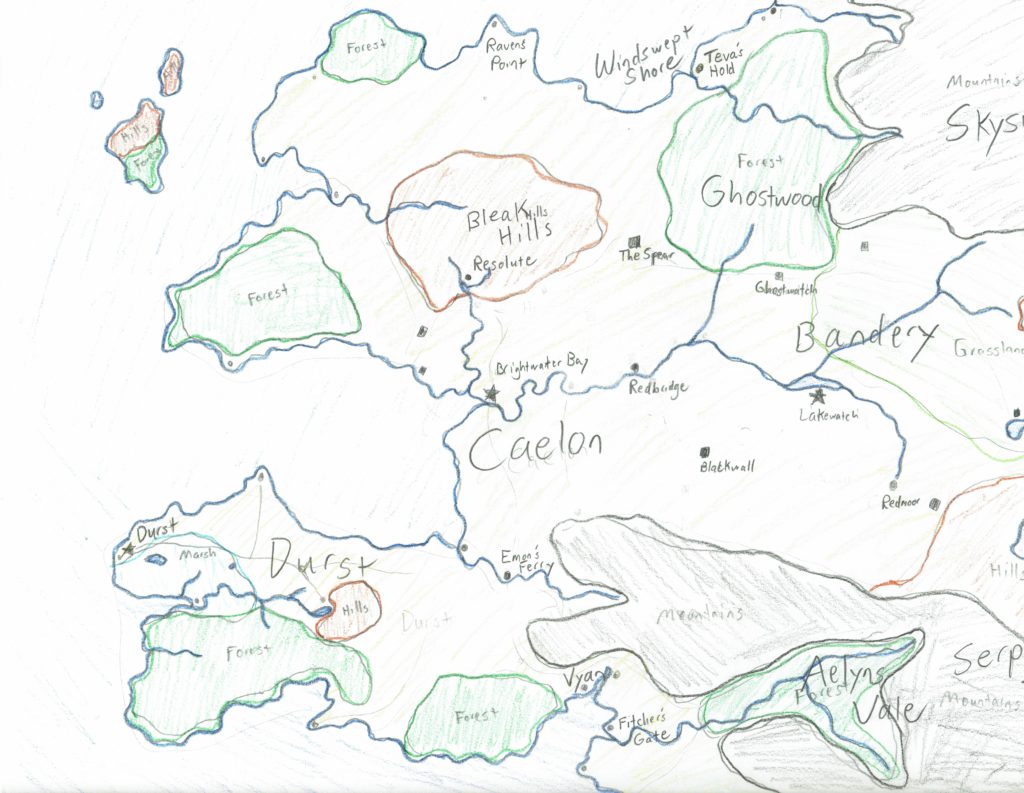

Today, I’m talking about mapping the setting. At least, I’m talking about how I built THIS map:

For THIS setting. This non-setting really.

Yes, I know the map has no names or labels. I’m working on it. It’s STILL in progress.

Let me be clear: this is NOT a careful explanation of the nuances of world and setting building. This is not setting building as creative art. This is “well, I’m gonna need a map for my campaign and I’ve got a couple hours to do it.” This is slapdash setting building. If you’re expecting complex theorycraft and stuff about how the map becomes a visual representation of the setting’s backstory and how to use it as such, sorry. This ain’t that. This setting has no backstory. It just is. Because we wanted to start playing now.

This also isn’t about how to draw a map. Though I am kind of proud of how those mountains look. I have always struggled with mountains.

Anyway…

Point is, this is the story of how I cranked out this map: the bare minimum I needed to get my campaign off the ground.

Do You Even Need a Map

When a GM sits down to design the setting for their upcoming campaign, the first thing they do is start drawing a map. Every time. Now, I know you’re expecting me to say at this point that I’m the only smart, sane person and I never ever start by making a map. That only terrible GMs who don’t understand setting building at all make a map.

Well, guess what? I almost always start by making a map. It’s fine. As long as you understand it’s totally unnecessary. I start with a map because I like to start with a map.

Look, I know I said I wasn’t going to get into theorycraft here, but I’m going to. At least a little. Because I don’t want to lead anyone down the wrong path. If you can’t – or don’t want to – produce a map like the one I made above, that’s totally fine. You can still totally build your own setting and run your own campaign in it. You don’t need maps. Maps are totally optional. And honestly, you don’t need much of a setting. Most of setting building is totally masturbatory. Or mapsturbatory. That’s what I’m calling it. Mapsturbation is all the crap a GM doesn’t actually have to do to make a setting that he does anyway because he describes himself as a “world building” GM. Mapsturbation is totally fine as long as you do it alone and don’t make anyone watch. Because no one gives a crap about your exposition.

The things you need to know about the setting to run a game in it almost never appear on the map. And the things you need to know about the setting vary from setting to setting. Because mostly what you need to do is establish a norm and then figure out the deviations from the norm. And that’s where genres and baselines come in.

For example, there IS a setting built into D&D. Core D&D. And core Pathfinder too. And I don’t mean the Forgotten Realms or Greyhawk or Galaxian or whatever the hell Paizo calls its world. It’s a setting defined by assumptions. It’s a fantasy world filled with the standard slew of magical races and mythical beasts. Technologically, it’s a mess of stuff from the late Roman Empire through to the early Renaissance. Except gunpowder. Unless there’s gunpowder. Politically, religiously, and socially it’s the modern world except that the predominant governing system is hereditary monarchies or aristocracies and the predominant religion is easily ignored polytheism that is ridiculously tolerant of atheism. They have nothing to do with actual feudalism or paganism. But they claim to be feudal. In short, it’s a standard high fantasy setting. And the players and the GM are on the same page, partly because of pop cultural exposure to said setting and partly because everything in the PHB is designed with that setting in mind.

Basically, that all provides the grounding so that everyone – GM and players alike – know what the world looks like, how the physics work, how society works, and that sort of thing. That provides the grounding.

All the GM has to do then is to specify the exceptions. “In my world, there’s gunpowder.” “In my world, magic is advanced and has filled the space of technology, so it’s more like the Renaissance and we have airships and magical robots.” “In my world, it’s a dark age, akin to Europe after the fall of Rome as civilization is recovering and it veers closer to actual feudalism. Well, actual Hollywood feudalism. Not quite Game of Thrones, but closer to that than the Kingdoms of Middle Zealand.”

That last one, by the way, is the exception that drags my world away from the Standard Fantasy Setting™. Dark age middle fantasy, I call it. Because I still like the magic stuff. I just tone it down. It’s not quite the brutal swords and sorcery of the Conan world, but it’s not quite “magic is everywhere” of modern D&D and Pathfinder. Gunpowder and freely available alchemical and magical items can just go die in the corner.

All of that stuff serves to ground the players – and the GM – in the fantasy reality. And, more importantly, to make sure they are all grounded in the SAME fantasy reality. That way, you minimize – but don’t completely eliminate – differences of agreement about what’s possible in the world and what the tone of the game actually is.

Once you’ve established that, what more do you need from your setting? Well, your setting provides two other basic things. First, it provides the backstory that gives context to the campaign and the campaign-related adventures. For example, if the campaign is about a band of heroic members of the great Empire fighting the evil Rebellion, your setting establishes the backstory of how the good Empire grew out of the dumb Republic that preceded it and came to power and who the evil Rebels are. Just as character backstory provides some context for what the characters are doing now and why they are doing – which is why too much backstory is a pointless waste because it doesn’t take much to do that – and just as the adventure background provides the context for the events and conflicts that the heroes are dealing with in that adventure, the setting backstory provides the context for the campaign. Which is also why setting backstory that begins with the creation of the universe is also usually a totally pointless waste. Unless the campaign is about resolving a conflict that started at the beginning of time.

Second, a campaign setting provides a space for the adventures to take place in. That much should be obvious. But there’s more to it than just “well, there’s an adventure in a forest so there’d better be a forest somewhere.” The setting actually provides all sorts of game elements that can be used to construct adventures and plot arcs. All of those cities in the Forgotten Realms and NPCs and locations and dungeons? Those are all basically there so that GMs can grab those bits and pieces and use them to make adventures out of. And, because they are part of the setting, they are interconnected. So it saves the GM time.

Look, if I decide I need an adventure to take place in an expansionist, militaristic kingdom, I can just create that kingdom when I need it. But if I drop that kingdom on the edge of the kingdom my campaign is currently taking place in, and that kingdom is a peaceful, pacifist, isolationist kingdom, there’s going to be some sudden questions about why the new kingdom – which has always existed – didn’t swallow the old kingdom centuries ago. And now I have some extra work. Otherwise, the verisimilitude of my world might take a hit.

Of course, verisimilitude matters more in some worlds than others.

The point is, the setting doesn’t just provide a bunch of game and plot elements that you can draw on to build your plots, it also makes sure those things have already been fit together in something resembling a reasonable world. So that every element you drop into the world feels like it was always a part of the world. Sure, a good GM can pull that trick off without having to preplan everything. I mean, hell, that’s mostly what I do. But you take a lot of pressure off yourself if you have this stuff figured out in advance.

Now, believe it or not, that’s about all a setting does. It grounds everyone in the same reality, it provides backstory for the campaign, and it provides a space for adventure and some elements that can be mixed into those adventures to tie the adventures into the world.

But there is also one optional thing that the setting also does. And it’s related to that last thing about providing game elements and a way to anchor them in the world. It also provides a way to anchor the players’ characters to the world. That is, the players feel like more of a part of the world if they can say “my character comes from this town or city or kingdom or village or isolated valley or whatever.” And that crap does far more to increase immersion than seven pages of useless backstory that never comes up during the game. And, I’ll save you the comment: no, letting the players make up the locations doesn’t matter one little bit. Not the littlest, tiniest bit. It is a myth – a damned, dirty lie – that giving the players ownership of a corner of the world, giving them narrative control, intrinsically increases immersion any more than anything else does. So, don’t bother.

But I’ll come back to that in a moment. Because I need to end this theoretical discussion of the use of setting by pointing out how much of this crap is optional and how much actually gets in the way for new GMs creating their own homebrew settings for their own adventures. And that plays into the question of “do you need a map?”

Look, the players have to be grounded in the reality of the world. That means you need to do that part where you specify the basic nature of the setting and then establish the exceptions. But that can be done in a sentence. Basically, you can just say, “like the D&D in the rulebooks except for this one detail.” Done and done. The backstory of the world only matters insofar as the campaign deals with the history of the world. If the players are fighting some ancient evil that was imprisoned a thousand years ago and threatens to pull apart the cosmos, yeah, you need that backstory. But if the players are adventuring adventurers who adventure, you really don’t. All the backstory you need is “a long time ago, there were lots of ancient kingdoms and empires. They all fell into ruin and left the landscape dotted with ancient adventuring sites filled with gold and magical treasure. Now get out there and have fun, you little scamps.” And that whole “pile of interconnected game elements to draw on?” Well, you can make that crap up as you go. Especially if you’re not running a complicated political thriller where the interconnections between all the stuff don’t matter. Need a city? Invent a city. Need a kingdom? Invent it. Need the details about the king? Come up with them when you need them. Don’t sweat it until then. As for where the players are from? If the adventure starts in their hometown, you’re already golden. And most campaigns start that way. But if the heroes are traveling, you can just name their places of origin and fill in the details later.

Building a setting is one of those things that takes as much work as it needs. It can be a huge undertaking, or it can take ten minutes and involve three sentences. And the amount that you actually need is usually pretty close to the “ten minutes and three sentences” mark. Even in a complicated game.

So now? Do you need a map? Well, a map is just a visual representation of all that crap. It’s just a way of organizing the geographical relationships between the game elements you invented and depicting the backstory and the basic nature of the setting. Maps vary. Maps of fantastic worlds will have floating islands and mysterious deserts in the middle of lush terrain caused by magical cataclysms. It’ll have hundred-mile-deep canyons filled with fire. Maps grounded in reality will look, well, real. Realish. I know some cartographic make a big deal about rain shadows and not putting deserts on the wrong sides of mountains based on rain shadows and figure out the plate tectonics of their worlds. That crap is inexcusably mapsturbatory. If you want to do it, fine, do it. But don’t make me watch. And don’t tell others they have to wank their maps the same way. I have once in my life – once in 30 years of gaming for more than a hundred players – had a player criticize one of my maps because of an ecological error. And that was because he was a biology major. And an asshole.

Even if you’re designing a complex setting, you don’t NEED a map. You just need that aforementioned grounding in the world thing, the important backstory elements, and a list of all those game elements that your setting already includes. Over the years, I have built up a generic fantasy world I run almost all of my D&D and Pathfinder worlds in. There is no map. There’s a list of regions and I have a vague understanding of where those regions are in relation to each other. But I’ve never bothered with a map. I’m not entirely sure I could make a map. I don’t think things fit together quite right. But I’ve never tried.

So, no, you don’t need a map. It’s mapsturbatory.

Mapping my Setting

Now, let me tell you how I made a map for my campaign.

I’m just kidding. I mean, I am going to tell you how I made the map. Except the map isn’t the important part. I’m actually going to tell you how I came up with the stuff on the map. The locations and landforms and stuff. The important bits. I decided to portray them as a map because, well…

Maps make the game better. I know I just got done saying that maps are completely unnecessary mapsturbation. And that’s true. I don’t want anyone out there feeling like they have to make a map to start a campaign. I’ve started many, many campaigns. Many didn’t have maps. A lot didn’t have maps when they started but eventually did have maps. You can skip maps. You can make them later. You can build them as you go. Or you can prepare one in advance. It’s up to you.

But there is a payoff. Maps make the world more real. Especially to the players. If all you have is some description of the genre and some “ands” and “buts” to describe the exceptions and a backstory and a list of important locations, sure, that’s enough to define a setting. But if you unfurl a map in front of the players and say “here, this is the world of Central Earth” and point out where Alice came from and where Bob came from and where the adventure starts and the Menacing Mountains of Madness and the Nonsensical Desert on the Edge of the Jungle, that makes the world real. And the locations get players excited. It incites their curiosity. In fact, let me tell you this: name one of your forests on your map Ghostwood. Holy crap. I have a Ghostwood on almost every map these days. For some reason, that particular name always gets someone to say “man, I want to go THERE!” Ghostwood. It’s like the best name for any map ever.

By the way, this is why most of my names are descriptive. Like Ghostwood and Bleak Hills and Serpents Teeth Mountains and Sunderlands. Those names excite people because they say something about the place. They are far more exciting than Valenar and Cormanthyr and Va’a’shal’das’t’ar’naeth’ven.

And that is why I draw maps that I don’t need. Apart from the fact that it’s fun, putting a map in front of the players anchors them in the world and gets them excited to explore it. Even if the map is nothing special, even if it’s just the standard collection of mountains and forests and kingdoms and ruins and fortresses, it’s a promise of a world to explore.

You don’t need a map. But if you can draw a map, draw a map.

A Setting from Nothing

So, there I was: I’d just had the Session 0 for my Pathfinder campaign and it had come up with absolutely nothing useful. I’ve talked about that. And I was about to have a character generation session based on a totally vague premise for the game that went something like “you all came to the town of Redbridge for the Spring Festival where something will happen that will involve a year of disaster if a bunch of heroes don’t deal with it.” I had no plan. Nothing. I didn’t know what was going to happen at the festival. I didn’t know what the Year of Disaster was all about.

What I did know was that I wanted a map. Because I like to be able to unfurl a map in front of my players and say, “here’s where you’re from and here’s where you’re from and here’s where you are now and here’s some enticing places that the game might go.” Because I didn’t really have a big plan for how the game was going to play out or what the campaign was going to be about, I didn’t have any big need for the map to depict any sort of backstory. Except…

The thing is, I was still keenly aware of the fact that I had literally no long-term plan for what might happen in the campaign. And I don’t like doing that. I wanted at least one idea for a potential conflict that might help drive the campaign. And this was before the character generation session. I knew the players wanted the chance to pursue their own personal goals, but I didn’t know what those goals were. So, I needed at least one story element I could fall back on to help me plan out future adventures.

Now, I can’t remember exactly when or how I decided on this. It probably had to do with a particular television show or movie or video game I was watching or playing while the campaign prep was rattling around in my head. That’s usually how it happens. Like, when I planned that campaign around sailing around different islands in a tropical sea, I was replaying Legend of Zelda: The Windwaker. And that’s how that happened. Yeah. That’s how I do things.

Anyway, something inspired me toward “escalating military conflict between two nations and who will stand up for the people who live on the border and aren’t involved either way but are going to get crushed?” That’s a pretty neat premise for a future conflict.

On top of that, I had decided that this campaign would take place in a region of the Angryverse known as The Western Kingdoms during The Dark Age. The Western Kingdoms is a collection of small, feudal kingdoms. Sparsely populated with a lot of frontier around them. Mostly feudal. They are the remnants of a borderland of the Great Empire of the previous age. The Zethinian Empire. The one that spanned most of the known world and which is responsible for all of those ancient ruins full of treasure. Of course, the remains of the Zethinian Empire still hold sway over another region of the Angryverse called Central Zethinia. But I didn’t want the growing conflict to involve the Zethinian Empire.

I have to stress that these “regions of the Angryverse” are just names and themes. If I want to run a game in the heart of a powerful, cosmopolitan kingdom, I run it in Zethinia. And I run it during the Age of the Empire. If I need Persia and the Middle East, that’s Alqad. If I want to do a game about colonizing the wild continent, I have the Southron Lands. Barbarians and nomads and swords and savagery? That’s the Sunderlands. Are they all basically clichés? Of-frigging-course they are. Because the whole point of setting the foundation for the world is to pick a foundation that is familiar enough to a lot of people that they can imagine the same world you can.

Now, to be totally and completely clear, I did this whole map thing in two steps. BEFORE the character generation session, I had a list of the things that had to appear on the map and had named many of them. AFTER the character generation session, I finished the map. But drawing the map was really just about taking the elements I’d picked and dropping them on the map.

So, given what I knew – Western Kingdoms, escalating military conflict, town with a festival for the PCs to come together in, and hometowns for all of the PCs even though I had no idea who the PCs were – I could at least come up with a list of elements that had to appear on the map.

A Hometown for Everyone

The most important thing I wanted from my map was the ability to tell each PC where they were from based on their background and character goals. Once they had created a character and had some idea of what that character was about, I had to place their hometown on the map. Or, at least, home region. As I said, though, I had no idea who the PCs were going to be. And so, I engaged in a trick I use often: a hometown for every archetype.

The basic idea is to look through your list of character generation options – races, classes, backgrounds if you’re using them – and make sure that each combination has at least one place they might be from. And to not make it obvious. I mean, some obviousness is unavoidable. It’s a human world, so the idea of multiple elven kingdoms or dwarven kingdoms is stretching it. So, you need the mountains of the dwarves and the forested valleys of the elves. And those shouldn’t be close together. After that, though, things get a little trickier.

First of all, there’s a split in my world between the New Gods – those of clerics and paladins – and the Old Gods – those of druids and rangers. Most of the world follows the New Gods. But some places still keep to the old ways. So, I would need at least two civilized human kingdoms. One that was closer to medieval feudalism and one that was closer to old-style paganism. Sort of a wild, borderland kingdom where civilization is less built up. Now, that might seem perfect because I was also trying to build an escalating military conflict, but I didn’t want the conflict to be spiritual because I didn’t want any divine characters in the party to feel split from each other. So, ultimately, I needed two good feudal New Gods kingdoms and one old, frontier kingdom.

Now, once upon a time, this region had been under the control of the Zethinian Empire. That was about 500 years ago. The way I saw it was that, basically, the peoples of the various towns were left fending for themselves for a while. Bandits and monsters did a real job on the region. Eventually, people starting fighting back. They became the lords. And eventually, they unified under one super lord. And that’s how kingdoms are born from a dark age. Except, as I thought about it, I decided the Old Gods kingdom probably never got pulled into the Zethinian Empire. It remained isolated the whole time. And it had to be strategically unimportant. Wild. Swampy. Hard to get to. That gives it a lot of character.

Meanwhile, the main kingdom was chugging along fine for a while, rebuilding itself and then, some lord decided it was time for him to carve his own chunk off the kingdom. And thus, I had two kingdoms. There was the vanilla medieval fantasy feudal kingdom ruled by a decent king and there was the more militaristic kingdom ruled by the ambitious king born of a rebellion umpteen years ago.

Thus, the central region of the Western Kingdoms were ruled by two kingdoms, Caelon and Bandery, with a disputed and built up border between them. And somewhere else, a bit isolated, was the small, pagan, frontier kingdom of Durst. Now, I needed a place for the really uncivilized. The barbarians and nomads and horse warriors. You know the types. Wild plains, steppe lands, ruins. They’re great for the PCs who reject civilization altogether – like barbarians – and also great as a place to spawn orcs for future adventures. Now, the Angryverse already has such a place. It’s called the Sunderlands. So, the Sunderlands are nearby. And that actually helped the backstory a bit.

So, maybe Bandery is the part of the Western Kingdoms that borders the wild barbarian and orc lands. It’s militaristic because it has to be. It defends the region from raiders and orcs and stuff. In fact, Bandery could essentially be the gateway into the Western Kingdoms. It has a rugged, easily defended border with Zethinia and an open border with the Sunderlands and so it has a strong military and a lot of fortifications and worships war gods and all of that. And then I realized I was mapsturbating unnecessarily and left that idea for future exploration. For now, I had what I needed. Almost.

Basically, all of the basic classes and races had places to hail from in my setting. But there’s other types of backstories. For example, what if I had someone who wanted to play a more traditional noble. Not a feudal lord – a warlord – but an aristocrat. A merchant prince type. Perhaps on a secluded edge of the map, there was a free city. Something closer in flavor to old Zethinia or the Italian city-states of the late Middle Ages. So, there needed to be the Free City of Vyan. Ruled by merchants and guilds and mobsters. And then I needed some unexplored, trackless wilderness dotted with small settlements of hardy people who struck out on their own. Hermits, rangers, fugitives, wizards, all those secluded lone-wolf types who take on promising apprentices and raise them in sheltered existences so they can be confused when they hit civilization proper.

And that covered pretty much every possible background option I could imagine. And I knew I could wing any other ones that came up. So, I had that list of locations. And all I had to do was turn it into a map.

Actually Drawing a Map

It’s hard to describe exactly how I drew the map itself. Because I just sort of did it. I needed to isolate the Western Kingdoms, so I surrounded it by water. The southern border, the one with Zethinia, needed to be rugged and easily defended. So, I put mountains there and a pass through them that Bandery could easily defend. To the northeast, I put the dwarf mountains. And in the southern mountains, I put the elf valley. To the east was the open border with the Sunderlands. The central land got split evenly between Bandery and Caelon. I was able to isolate Durst on a peninsula. The northern third of the map was unclaimed land. Forests, hills, rugged mountains, an untamed island, all good places for adventure. Crammed in on the southern shore, isolated by mountains and wilderness, was Yvan the Free City. It was near the elf valley, though.

Basically, I just started blobbing this stuff all out on a sketch map. I moved things around. Placed towns and fortresses. Named some features. Made sure there was a lot of empty space so the map would look sparse, and then I colored it in to make it easy to see what I’d done.

And then I threw that map on a light table and drew an actual nice map over it. And that’s the map we started with. This map:

And Redbridge – the start of the campaign – was pretty much in the dead center. It lay inside Caelon, but near the border with Bandery. And man did that placement change the town. But that’s a story for another time. As for where everyone came from and why? Well, that’s also a story for another time. Because that became a part of planning the first adventure. So, we’ll cover that another time too. For now, though, you know how to build a setting map based on almost nothing that will get you ready for anything.

If you even bother drawing a map.

Pathfinder? I am fairly sure that Pathfinder was abandoned in favour of 13th Age.

I’m running more than one game. The 13-Age game is online. The Pathfinder game is a meatspace game.

Looks great! I need to practice my mapping chops. I spent a fair time mapping when I was younger, but then I fell out of the hobby. When I came back to it several years ago I started doing everything online so I never quite picked up mapping again. It was fun though so I should restart. Thanks for the soothing article!

This is my favorite type of article – the type that gets me thinking about planning, gets my creative juices flowing, and gets me thinking through next steps in my current campaign – and what to play next.

Just a little something that sparkled at me while I read this: please do write something, someday, on campaigns about colonizing the wild continent? 😀

*shows awesome map*

“This is “well, I’m gonna need a map for my campaign and I’ve got a couple hours to do it.” This is slapdash setting building.”

Must you rub it in your face how great your mapping skills are?

Just keep in mind that you could run a game just fine on the blobby map he started from.

Okay, the blobby map was slapdash crap. And then I decided to make a good one on top of it. But that’s why the nice one isn’t finished. Because I didn’t have time to do that kind of thing.

Well, even the blobby map is just plain awesomeness!

The first map is a cross between a graphic organizer and a representation of reality, but that’s still going to work fine for keeping you consistent on the key setting points, like you were saying.

I also prefer ‘colorful place names’ on home made campaigns. Similar to what you said, having “The Corpse Marsh”, “The Grimwood”, and “Black Peak” are more evocative and easier to remember. I’ve gone so far as to just call the adventuring realm “The Marklands”, the ruler “The Margrave” , the parent realm “The Kingdom”, etc. Player’s have a hard time remembering NPC names, place names, and realm names, and end up giving them stupid little nicknames anyway. So I beat them to it.

I highly recommend Wonderdraft for making maps. Yes, it costs money ($30 now I think). But it makes beautiful maps and it super novice friendly. I literally made my first map in about 20 minutes and my players loved it.

Hey Angry,

When you were placing the settlements did you have any idea of the scale or travel time between the settlements?

Just kind of curious.

A way to start at an even rougher level of detail is to start with a single adventure site, and then draw up a list of the most likely next destinations, with distances and general directions. I’d probably want to switch to a blobby map pretty soon after the campaign reached a second hub location.

One interesting thing I did with my main continent, was include a Recently Lost Kingdom. That is, a kingdom that lost its independence and was broken up within the last few hundred years. The people in that territory still have a recognizable culture and some lingering hopes of reviving their homeland, but that’s about it. It makes for some interesting variations in historical events.

To my mind, a municipal dot on the map only really needs three things: a name, a size (village/town/city), and a product. Why a product? Because trade happens and that’s probably the most common way you’ll ever interact with or see evidence of a settlement that you’ll never visit. The “product” can be abstract too; maybe it’s a college town or a trade hub.

Also, you forgot the hereditary megacorps and the postwar jitters. 😉

That “product” idea is interesting.

Just giving every town their one small thing that distinguishes them from the next town over, whether that be a chief export of sheep, lumber or knowledge.

It’s a nice touch, I might steal that. Thanks. 🙂 xx